New population estimates released this week by the U.S. Census Bureau suggest that the shifts in political power after the 2030 census could be among the most profound in the nation’s history.

Once a decade, the Constitution requires the reallocation of congressional seats among states based on the results of the latest census, a process called reapportionment.

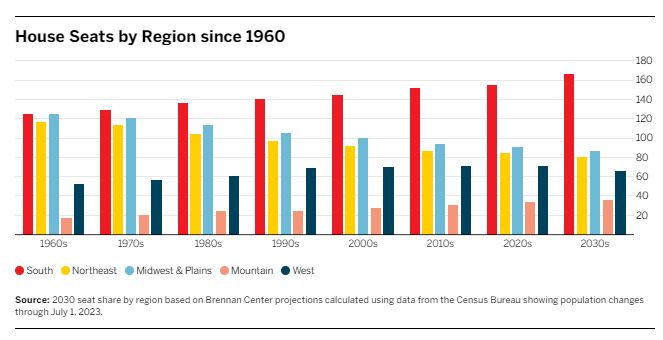

In the post-World War II era, the nation’s reapportionment story has largely been one of a steady shift of political power to western and the southern states at the expense of northeastern and midwestern states. Postwar domestic migration and immigration, for example, helped California more than double the size of its congressional delegation between 1940 and 2010.

So far, the story this decade is shaping up to be different.

While southern and mountain states have continued to grow at a steady clip since the Covid-19 pandemic, the rest of the country, including one-time boom states like California, has seen mostly flat growth or even population losses.

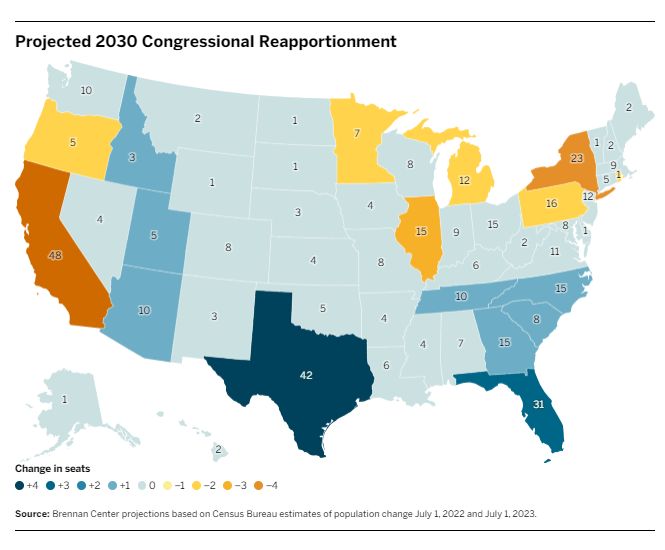

If these trends continue for the balance of the decade, California would lose 4 of its 52 congressional districts in reapportionment — only the second time the Golden State has ever lost representation. New York, meanwhile, would lose three seats, Illinois two, and Pennsylvania one, leaving all three states with congressional delegations half the size they were in 1940.

By contrast, the South has emerged as this decade’s growth engine, adding almost 3.9 million people and accounting for nearly all U.S. population gains since 2020.

Four booming southern states stand out in particular: Texas, Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina. These rapidly growing states by themselves account for more than 90 percent of American population gains since the 2020 census, with Texas and Florida alone accounting for 70 percent of growth.

Based on the most recent trends, Texas would gain four seats and Florida three seats in the next reapportionment, placing Texas within striking distance of becoming the largest state, perhaps as early as 2040. Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee also would each gain a new congressional seat, as would three mountain states: Arizona, Idaho, and Utah.

These changes would solidify a shift in the regional balance of power. Whereas in 1960, the South, Midwest, and Northeast regions all had roughly the same population, by 2030, the South will be by far the country’s most populous region and home to nearly 4 in 10 Americans.

And, although the Census Bureau won’t release updated figures on the racial and ethnic components of population change until next July, it is all but certain that in most of the country’s increases in population will be driven largely by growth in communities of color.

Of course, the magnitude of reapportionment changes might not end up being as large as currently projected, given that it is still relatively early in the decade. For example, the significant migration of recent years to southern and mountain states might slow as higher interest rates and rising housing costs impact the willingness or ability of people to move. In similar fashion, a return of international immigration to pre-2017 levels — or something higher — could help stabilize populations in states like California and New York, both of which have seen large outbound migrations of native-born residents of all races to other states in recent years. There are signs that some of this may be happening: the most recent census figures for the period between July 1, 2022, and July 1, 2023, show a decrease in the heightened outbound migration of the pandemic years.

But the general trend lines seem fairly clear. Barring something completely unforeseen, the 2020s are shaping up to be the South’s decade. And that, in turn, will have major ramifications for fair representation and fair maps.

Michael Li serves as senior counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, where his work focuses on redistricting, voting rights, and elections. Prior to joining the Brennan Center, Li practiced law at Baker Botts L.L.P. in Dallas for ten years. He was the author of a widely cited blog on redistricting and election law issues that the New York Times called “indispensable.” He is a regular writer and commentator on election law issues, appearing on PBS Newshour, MSNBC, and NPR, and in print in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Roll Call, Vox, National Journal, Texas Tribune, Dallas Morning News, and San Antonio Express-News, among others.

In addition to his election law work, Li previously served as executive director of Be One Texas, a donor alliance that oversaw strategic and targeted investments in nonprofit organizations working to increase voter participation and engagement in historically disadvantaged African American and Hispanic communities in Texas.

Li received his JD with honors from Tulane Law School and an undergraduate degree in history from the University of Texas at Austin.

Gina Feliz is a Program Associate in the Democracy Program, where she focuses on voting rights and redistricting. Prior to joining the Brennan Center, Gina worked as a Development Assistant at the Housing Development Fund in Stamford, CT.

Gina graduated with honors from Princeton University in 2022 with a bachelor’s degree from the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, and a certificate in African American Studies. For her undergrad independent work, Gina researched the civil and criminal legal systems, focusing on court fees & fines and the criminalization of immigration. While at school, Gina was an organizer for a student group advocating alongside and on behalf of justice-impacted individuals in the NJ area; volunteered as an instructor for English-as-a-Second-Language Students in Trenton; and interned at Legal Services of New Jersey.

The Brennan Center for Justice is a nonpartisan law and policy institute.

We strive to uphold the values of democracy. We stand for equal justice and the rule of law. We work to craft and advance reforms that will make American democracy work, for all.

Spread the word