In 2023, the issue of child labor re-emerged as a national crisis. Federal data on the rise of child labor violations and numerous investigative reports of widespread illegal youth employment garnered sustained media attention, sparking outrage from the public and lawmakers alike. At the same time, EPI has documented an ongoing, coordinated effort to roll back existing child labor protections that is gaining momentum in states across the country. Legislative proposals to weaken child labor protections—some of which have already been enacted—allow employers to hire teens for more dangerous jobs or extend the hours young people can work on school nights.

What has received far less attention is the long-standing system of pay discrimination against young workers under federal and state laws. These laws allow employers to pay youth less than adults in the same jobs and, in many cases, exclude young workers from the minimum wage protections that cover most adult workers.

In states across the country, advocates and lawmakers are working to eliminate subminimum wages for low-wage tipped or disabled workers. Amid increased child labor violations and a growing movement to roll back protections for working youth, lawmakers should also work to eliminate youth subminimum wages. Age-based pay discrimination is unfair and harms workers of all ages.

The gaps in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA): Which workers are excluded?

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA) is the New Deal-era landmark law that established many basic worker rights—the minimum wage, the right to overtime pay for work in excess of 40 hours per week, and safeguards against oppressive child labor. The FLSA applies to all businesses involved in interstate commerce or conducting $500,000 in business annually, as well as health care facilities, schools, and government agencies. Most employers are covered by the FLSA’s labor standards.

However, workers in many occupations remain excluded from the Fair Labor Standard Act’s protections. Workers in agriculture and domestic work were originally excluded from the law’s protections, a legacy of racism and sexism toward Black workers, workers of color, and women who historically and presently have been occupationally segregated into these industries. Tipped workers in service industries like restaurants, bars, and salons—who are disproportionately women and people of color—were also initially excluded from the FLSA’s protections.

Since the 1966 amendments, tipped workers receive basic labor protections but legally can still be paid subminimum wages by their employers. By law, employers must ensure that tipped workers earn enough per hour from customer-provided tips to make up the difference between the tipped wage and the regular minimum wage though this requirement is often ignored since it is difficult to enforce. Domestic workers, who are primarily women of color, did not receive FLSA coverage until 1974.

Farmworkers, who are primarily immigrants and workers of color, remain excluded from the FLSA’s overtime provisions (many are also excluded from minimum wage protections), and the FLSA’s child labor provisions in agriculture remain much weaker than those governing non-agricultural employment. The FLSA also continues to exempt many other workers including incarcerated workers and independent contractors (from all FLSA protections) and disabled workers (from minimum wage protections under Section 14C).

Amid a growing bipartisan recognition that paying workers subminimum wages based on their disability status is discriminatory and unjust, 14 states have eliminated subminimum wages for disabled workers in recent years. Meanwhile, eight states and the District of Columbia have eliminated the subminimum wage for workers who receive tips. Yet, the implications of allowing employers to pay young workers subminimum wages—often for performing the same work as adults—have, so far, remained largely unexamined.

Age-based discrimination in federal minimum wage law

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, child labor was widespread and unregulated. While the children of wealthy industrialists learned to read and write, their parents profited from the labor of poor children in their employ. These children toiled for long hours in dangerous conditions for negligible wages. Unsurprisingly, employers generally opposed government regulation of child labor, and state-level progress on child labor proved challenging.

As a result, reformers pursued federal regulation, first achieving fleeting progress through the 1916 Keating-Owen Act, and finally securing the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. Though the FLSA enshrined protections against excessive and hazardous child labor into federal law, it also established subminimum wages for youth, students, and occupations often held by youth.

Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA):

- Youth under 20 can be paid as little as $4.25 per hour for their first 90 calendar days of employment (Federal training wage, also known as the “Youth opportunity wage,” 29 U.S.C. §206(g))

- Full-time students can be paid 85% of minimum wage when employed in retail or service establishments, agriculture, and institutes of higher education (§ 519)1

- Messengers, learners (including student-learners) and apprentices of any age can be paid 75% of minimum wage, subject to approval and issuance of a certificate from the Wage and Hour Division (§ 520.506)2

- Specific occupations typically held by young workers are exempt from minimum wage law. These occupations include:

- Babysitters who work fewer than 20 hours per week (§ 552.104)

- Workers at seasonal amusement or recreational establishments and organized camps (§ 213(a)(3))

- Newspaper delivery workers (also exempt from child labor law, § 570.124)

As shown, the FLSA discriminates against young workers based on their age, student status, or occupation (or some combination of these factors). The Fair Labor Standards Act also excludes from minimum wage protections several occupations often held by youth. Yet, in the low-wage sectors where youth are typically employed (largely leisure, hospitality, wholesale, and retail), young workers are performing the same work as adults, with some exceptions based on federal child labor protections from excessive or hazardous work. In cases where a young person is being trained to perform a new job, the federal minimum wage is designed to provide a time-limited floor that employers can exceed.

Modern youth subminimum wages are a persistent relic of employers’ past and present interest in children as pool of exploitable, low-wage workers.

Which states have weaker or stronger protections for young workers?

Though the FLSA permits youth subminimum wages and exempts some youth occupations from FLSA protections, states can set standards that exceed (but do not fall below) the FLSA. Whichever standard is stronger prevails. For example, because Congress has failed for over a decade to increase the FLSA-established federal $7.25 minimum wage, 30 states and the District of Columbia have adopted higher minimum wages.

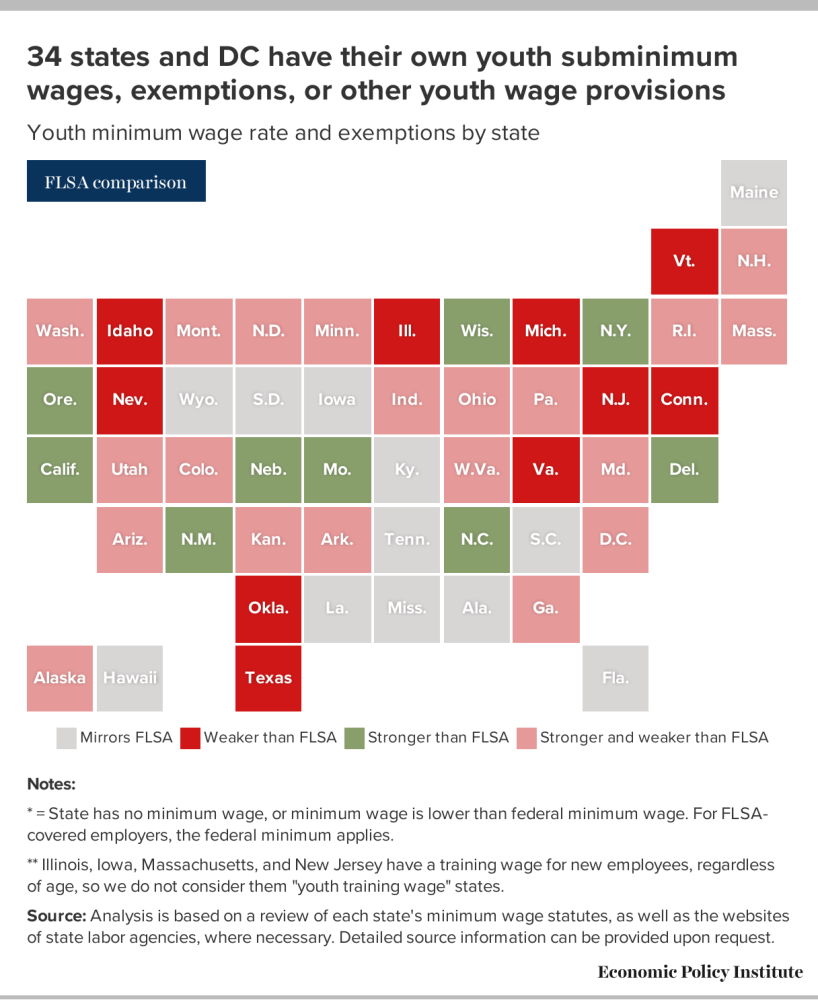

On January 1, workers in 22 states saw new increases to the minimum wage. Yet, in some of these states and many others across the country, employers can pay youth below these rates. Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have provisions in laws that permit employers to pay minors less than adults in the same roles based on age, student status, or occupation, or exempt young workers entirely from state minimum wage protections.

Some states mirror federal law, but most have weaker protections for young workers

Nine states already exceed FLSA standards. Twelve states and Puerto Rico mirror the youth exemptions and youth subminimum wages that exist under federal law. However, it is more common for states to have weaker protections for young workers than under the FLSA. These states have more exemptions for youth workers than under federal law or allow youth to be paid a smaller share of the minimum wage than allowed by federal law. 3 (See Figure A).

While many states have improved upon federal standards in some areas—by limiting or eliminating exemptions and reduced wages—many of these states maintain standards that are weaker than the FLSA in other areas. Figure A shows how each state compares with the FLSA on minimum wages for youth.

The complexity of state and federal law increases the likelihood of youth exploitation

States’ treatment of youth subminimum wages generally falls into one of four categories:

- State law mirrors the FLSA—youth workers are treated the same under state law as they are under the FLSA

- State law is weaker than the FLSA—youth workers can be paid a smaller share of the minimum wage than what FLSA allows, or there are more coverage exemptions than FLSA

- State law is stronger than the FLSA in some areas but weaker in others

- State law is stronger than the FLSA in some areas (and may mirror it in others)

These categories and the categorization of states into these groups are imperfect. The way states treat youth workers with respect to the minimum wage can be extremely complex. This complexity harms young workers by allowing employers to “game” the law, making it harder for youth to know their rights, and complicating labor law enforcement.

Nine states and the District of Columbia practice age-based pay discrimination that is not time-limited: Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, New Hampshire, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Washington. In these places, employers can legally pay certain categories of young workers a subminimum wage on a permanent basis, solely by virtue of their age. This differs from the FLSA’s requirement that workers be “full-time students” to be paid a subminimum wage indefinitely. For example, in Washington, all minors under the age of 16 can be paid 85% of the state’s regular minimum wage. Some states treat full-time students differently from the FLSA, such as Massachusetts, where students can be paid 80% of the minimum wage as opposed to the FLSA’s 85%.

In addition to paying subminimum wages indefinitely to workers based on age, four of these permanent subminimum wage states (Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, and Michigan) and the District of Columbia also exempt certain youth or pay some youth subminimum wages temporarily. For example, in Maryland, youth under 18 can be paid 85% of the minimum wage, but youth under 16 who work fewer than 20 hours a week lack minimum wage protections.

In 19 states and the District of Columbia, some or all youth workers are exempt from the minimum wage floor because they are not even considered “employees.” In these states, youth or student workers at FLSA-covered employers would be eligible for the federal minimum wage, but workers in non-FLSA-covered employers would have no minimum wage protections at all. For example, Nevada exempts all youth under 18, Alaska exempts all youth under 18 who are employed for fewer than 30 hours per week, and several states exempt youth under 18 if they are enrolled in school or work part-time.

Nineteen states exceed the FLSA’s youth subminimum wage provisions in some areas but are weaker in other areas

Nineteen states have limited provisions that exceed federal standards under the FLSA but also contain youth subminimum provisions that make state law weaker than the FLSA in other areas. In most cases, this means the state has no youth training wage—a subminimum wage paid to workers under 20 for the first 90 days of employment—but has additional youth exemptions or subminimums or exemptions that do not appear in federal law. For example, New Hampshire has no youth training wage but allows minors under 16 to be paid 75% of the state minimum wage. In Minnesota, youth under 20 can be paid $8.63 for the first 90 days of employment (higher than the federal training wage but lower than the state’s minimum wage), while youth under 18 can be paid $8.63 indefinitely, and some youth work in agriculture and at recreational programs that are completely exempt from minimum wage laws.

Nine states exceed federal standards for youth wage payment

Only nine states appear to exceed the FLSA in some areas while mirroring it or exceeding it in others. These states are California, Delaware, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, and Wisconsin. They do not allow youth subminimum wages or youth exemptions that are not present in the FLSA, or their training wage share of the regular minimum wage exceeds that of the FLSA. In Missouri, Nebraska, and Wisconsin, the youth training wage is higher than the $4.25 federal rate (but still lower than the state’s regular minimum wage). Delaware and New Mexico have no youth subminimum wages, training wages, or exemptions for youth. (See the map for more details.)

A mixed bag on strengthening youth protections: State efforts to eliminate the youth subminimum wage have achieved some success, but attempts to lower pay for youth remain an active threat

In contrast to the campaigns to eliminate subminimum wages for tipped or disabled workers, attempts to do the same for young workers have been slower to gain traction. But there have been some hopeful signs recently. In 2021, Delaware and New Mexico passed bills eliminating youth subminimum wages. The Delaware bill eliminated youth training wages and subminimums, while the New Mexico bill eliminated youth subminimums and exemptions for youth.

In 2023, a Rhode Island lawmaker proposed eliminating the youth subminimum wage, and a Kentucky lawmaker proposed eliminating subminimum wages for disabled, tipped, and youth workers. Additionally, a 2024 ballot measure in Michigan would raise the minimum wage and eliminate all subminimum wages. At the federal level, the recently reintroduced Raise the Wage Act of 2023 would phase out subminimum wages for tipped workers and disabled workers and phase out the $4.25 training wage for youth workers under 20.

But at the same time, lawmakers in several states have proposed new youth subminimum wages in recent years. In 2019, Arizona, Arkansas, and West Virginia considered but did not pass bills to implement youth subminimum wages or to exempt seasonal workers (which are often youth) from minimum wage law in the case of West Virginia. In 2021, a Florida senator proposed implementing training subminimum wages for all workers during the first six months of employment. And in 2023, lawmakers in Maine, Nebraska, and Virginia introduced new youth subminimum wage bills.

Youth subminimum wage laws allow employers to undervalue and exploit youth for profit

Advocates of rolling back protections for youth workers want it both ways. These advocates want to treat young workers more and more like adults in terms of work hours and hazardous occupations, but then justify paying lower wages on the basis of age.

Supporters of youth subminimum wages and of rollbacks of child labor protections present themselves as champions of youth opportunity and skill building, but their economic arguments aren’t supported by evidence. For instance, supporters of youth subminimum wages have claimed that young people will be denied job opportunities under higher minimum wages, but research has shown that higher minimum wages have no meaningful impact on teen employment.

An analysis of Maine’s 2018 youth subminimum wage bill by the Maine Center for Economic Policy estimated that 27% of youth who would have been impacted by a youth subminimum wage were already living in or near the poverty line. True champions of youth would work toward policies that advance youth economic wellbeing and reward hard work, not erode the wage floor youth depend on to support themselves and their families.

Those seeking to weaken child labor laws have a straightforward goal—expanding employer access to cheap labor and reducing employer liability. To that end, these parties are using an ongoing, coordinated campaign to not only erode protections against oppressive child labor but also legalize common forms of employer violations. For example, instead of complying with hours restrictions, industry groups representing businesses are instead attempting to weaken those restrictions. Youth subminimum wages, rising child labor violations, and threats to protections against oppressive child labor are inextricably linked in the push to exploit cheap labor.

Moreover, expanding the labor pool to more young people, without providing them the same protections afforded adults, puts downward pressure on wages for all workers in industries that employ youth. If a business can hire a 16-year-old to perform the same job as an adult, but pay them less, that employer has little incentive to raise pay to attract and retain those adult workers. Age-based subminimum wages also create incentives for employers to fire staff when they reach adulthood if employers can find new young replacements easily.

Lawmakers should eliminate youth subminimum wages

Modern society has established guardrails around child labor to intentionally address the unique vulnerabilities that youth face in the workplace—including threats to academic and behavioral outcomes, risks of injury and exposure to long-term health impacts, and high rates of workplace violence and wage theft. But teenagers’ labor is not worth less to employers and our economy, and wages should reflect this reality. At a time when child labor violations are on the rise, policymakers should seek to raise—not lower—standards and strengthen protections for youth in the workplace. Youth and adult workers, especially in the lowest-wage industries, will benefit.

To put an end to youth subminimum wages at the federal level, lawmakers could pass the Raise the Wage Act of 2023, which—beyond raising the federal minimum wages for all workers—includes a phaseout of the training wage for youth under 20. Federal lawmakers should also eliminate subminimum wages for full-time students and exemptions in the FLSA that deny minimum wage protections for occupations that are often held by youth, such as babysitting, newspaper delivery, and seasonal recreation work.

State lawmakers have a key role in eliminating youth subminimum wages at the state level, where a complex set of rules and exceptions interact with federal law to produce a confusing system of wage payment laws that invite exploitation and hinder enforcement. Proposed or recently enacted bills to eliminate youth subminimum wages can serve as a guide for state lawmakers seeking to reform and simplify these laws.

Young people deserve to be paid at least the same minimum wage to which adult workers are legally entitled. Anything less is discriminatory, exploitative, and harmful to workers of all ages.

Notes

1. Full-time students can be any age but are typically youth. The FLSA definition of a full-time student is “a student who receives primarily daytime instruction at the physical location of a bona fide educational institution, in accordance with the institution’s accepted definition of a full-time student.”

2. Messengers, apprentices, and student-learners can be any age, but apprentices and student-learners tend to be teenagers and young adults who are being trained to work in a particular field.

3. This blog post considers states to have weaker standards than the FLSA if they pay youth a lower percentage of the regular minimum wage, even if that subminimum exceeds the federal minimum wage. For example, Illinois allows youth under 18 who work fewer than 650 hours per year to be paid $10.50 or around 81% of the state’s regular minimum wage of $13. Though $10.10 exceeds the federal minimum wage, 81% is a smaller share of the minimum wage than the FLSA mandates (85%).

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.

Spread the word