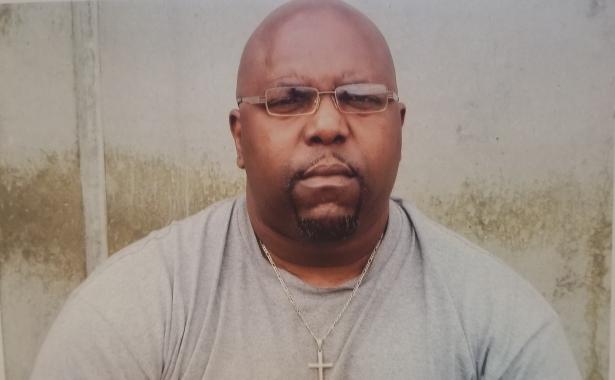

About fifty men are gathered in a small prison chapel. Most are regular attendees of the only inmate-led service on the compound, which meets every Wednesday night. There is no preacher from the free world who has brought this group together. Instead, it is Terrence Heard—a well-respected, learned, and incarcerated minister. Heard strikes an imposing figure, but his smile and laughter bring an infectious joy to anyone around him. Tonight, he is speaking to a crowd that includes some men who are gang affiliated.

Heard, who was convicted of charges related to a murder during a kidnapping, has been serving a life sentence plus twenty-five years since 1997. If he had taken the State of Tennessee’s plea deal for fifteen years, he would be a free man right now.

Heard claims he did not murder anyone, and court testimony backs him up. He will die in prison if the state’s sentencing laws remain the same. There are currently bills in both the Tennessee House and Senate—HB 2785 and SB 2725—that, if passed, could lessen Heard’s sentence as well as that of many others. The bills remove the criminal responsibility for conduct of another person—a reversal of what is often categorized as “felony murder,” various laws enacted around the country which hold people liable for murder if they participated in or were present for a crime that resulted in someone’s death. If the legislation passes in Tennessee, Heard would be able to reverse his first-degree murder conviction.

As a member of one of several sets of the “Gangster Disciples” in Memphis, Heard was convicted on September 15, 1998, after witness testimony identified him as being involved in the kidnapping and assault of Ricky Aldridge and the kidnapping and murder of Marshall “Pokey” Shipp.

On November 28, 1997, the Associated Press reported that “Marshal ‘Pokey’ Shipp made a fatal mistake. He stuck his nose in gang business where it didn't belong, a court witness said. Ricky ‘Kuboo’ Aldridge, twenty, said he and Shipp, his thirty-one-year-old cousin, fell afoul of the Gangster Disciples, were tried by the gang, and beaten for their indiscretions.”

The article goes on to explain that Aldridge survived the encounter and testified against thirteen young men, “all identified as gang members.” Of the thirteen, five were charged with kidnapping, robbery, and first-degree murder. The other eight faced facilitating murder, robbery, and kidnapping.

During the trial, Heard’s name would not appear in any newspaper article in relation to the case, though he faced the same trial and charges for Shipp and Aldridge. He would eventually be lumped together as one of fifteen gang members involved. It wasn’t until October of 2021, on the back pages of The Commercial Appeal, a Memphis daily newspaper, that Heard’s fate was covered in twenty-three words: “The following was convicted by jury after trial: Terrence Heard, first degree murder, life imprisonment; two counts especially aggravated kidnapping, twenty-five years.”

Heard has been in prison for twenty-six years. The story of how he got there, buried in newspaper clippings and court records, poorly captures the past two and a half decades of his life. Without looking at how Heard has spent these years in prison, he would be just another faceless gangster—one of the more than 50,000 Gangster Disciples across the country. I’ve known Heard for about twenty-five years. I ran into him at the first prison I was assigned to in Whiteville, Tennessee. I was naïve to prison culture and especially gang culture. I was told to steer clear of the gangs. My impression of him was simply that I didn’t want to be around him—he had a seemingly intimidating manner as he moved through the prison with his fellow gang members.

After twenty-eight years in prison now, I have learned more wisdom when it comes to making snap judgements of people. When I first met Heard, I knew nothing about the life that originally led him to join the gang.

I did not know that both his mother and father were in and out of prison, and gangsters themselves. I didn’t know that he had lived as a homeless person for many of his teenage years and that his desire to be safe while living in the streets of Memphis pushed him toward gang life.

Years passed, and later, after many prison transfers, I met Heard again in Clifton, Tennessee. At that point, he had been in Clifton since 2003. He is now my dear friend.

After getting his GED in prison, he embarked on self-led education, intensely studying the Bible and other Christian texts. Many of us have been inspired by Heard and his words. He became a moral compass that others look to in order to find direction. He’s a gentle bear whose strength is in words and not in violence, in love and not in chaos. He is slow to speak, choosing his words carefully and deliberately. He is always well prepared, well read, and fully engaged when speaking to one person or a group of people. His life story, his ongoing battle for freedom, and his great faith allow those around him to believe that change is possible, and that hope is on the horizon.

Terrence Heard and his wife, Adrienne Heard (courtesy of Adrienne Heard).

Affiliated and non-affiliated church goers listen intently to Heard’s sermons. “When my life began to unravel in a way that took me down a crash course, and my soul was hurting, and my heart was broken,” he said at one service, “the one thing that kept me from totally sinking is my faith in God.”

I asked him one day about how he got in this predicament. He said, “I was just twenty-four, and the organization [the Gangster Disciples] was a big deal in my young eyes. I wasn’t bold enough to challenge them. I was offered a plea deal for facilitation with a sentence of fifteen years at 100 percent. I refused the plea deal . . . primarily because I struggled with the thought of taking responsibility for the death of Mr. Shipp. I don’t deserve to be in prison for his murder. The young man that I was, that associated himself with that organization, has long turned his life around for over two decades now.”

I’ve learned a great deal about myself, the justice system, and the culture of prison by observing and listening to Heard. What I can say with confidence is that I’ve learned that we cannot always count on the justice system to get it right and that there is always more to the story if one takes a little time to discover what’s underneath appearances.

What does it say that the justice system felt it appropriate to offer Heard fifteen years for his part in the crime, but decided at trial to make him pay severely for declaring his innocence of murder, and give him more than a life sentence? How is justice served by keeping Heard in prison forever?

The United States is the only country that still uses the “felony murder” legal doctrine—and it has impacted thousands of people across the country, targeting youth, women, and people of color. There has been momentum toward reform, with states like Illinois, Colorado, and California passing bills like what has been proposed in Tennessee.

There is no transparent data on how many people in Tennessee are impacted by felony murder, but through my own experience of incarceration, I have met others like Heard. If these bills pass, Tennessee would join the group of states pushing for reform and resentencing of people who did not commit murder, but are spending life in prison under first-degree murder sentences.

Nothing can erase the twenty-six years that Heard has been incarcerated. But with this proposed legislation, Tennessee has an opportunity to correct an injustice that has been placed on Terrence Heard and many others.

Tony Vick has served almost three decades of a life with parole sentence in Tennessee. He writes about captivity in the hope of contributing to the prison reform movement.

Brandon Arvesen teaches undergraduate writing at Colby-Sawyer College in New London, New Hampshire. He is the founding editor of 3cents Magazine, a managing editor of True Magazine, and a nonfiction writer.

Since 1909, The Progressive has aimed to amplify voices of dissent and those under-represented in the mainstream, with a goal of championing grassroots progressive politics. Our bedrock values are nonviolence and freedom of speech. Based in Madison, Wisconsin, we publish on national politics, culture, and events including U.S. foreign policy; we also focus on issues of particular importance to the heartland. Two flagship projects of The Progressive include Public School Shakedown, which covers efforts to resist the privatization of public education, and The Progressive Media Project, aiming to diversify our nation’s op-ed pages. We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Spread the word