Iran has taken a turn that hardly anyone could have seen coming a few short months ago. For years, Iran’s reformist faction has languished in the political wilderness, banished there by hard-liners more aligned with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and by a disillusioned electorate convinced that its votes did not matter. Few imagined this year that the reformists were about to make a comeback and elect a president for the first time since 2001. Yet on July 5, this is precisely what happened.

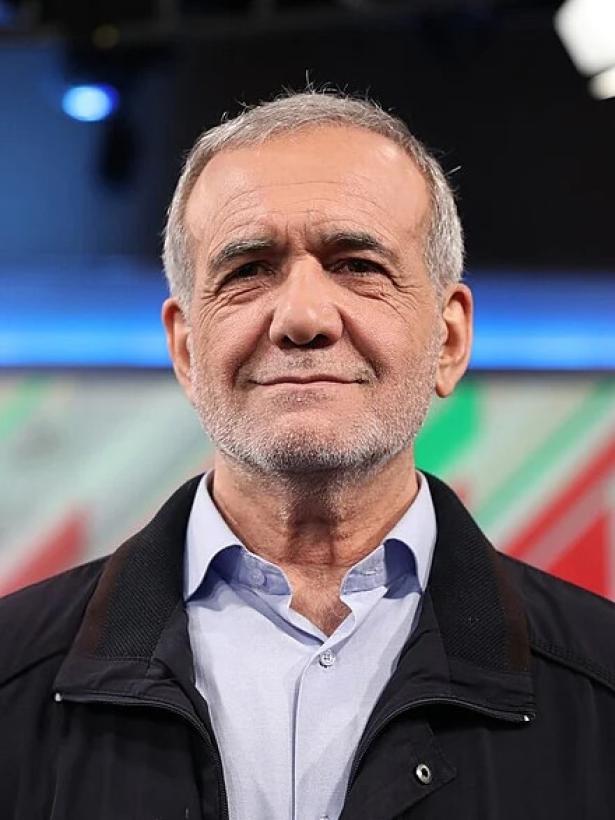

Masud Pezeshkian, a physician and longtime member of Parliament, defeated the ultra-hard-liner Saeed Jalili in a runoff with 54.8 percent of the vote. Turnout was extraordinarily low in the first round and only somewhat higher in the second, according to the official numbers—meaning that Pezeshkian will become president with a smaller share of eligible voters than any other president in the history of the Islamic Republic. For many of those who did come out, the main motivation was not love for Pezeshkian, but fear of his rival.

In effect, Iranian citizens sent two negative messages this election week: Those who didn’t vote demonstrated their rejection of the regime and its uninspiring choices. Those who did vote said no to Jalili, who represented the hard core of the regime and its extremist agenda.

Khamenei could have avoided this outcome by simply not allowing Pezeshkian to run. The Guardian Council, an unelected body, vets all candidates for office and is ultimately loyal to the supreme leader. So why did Khamenei allow this election to become a binary choice pitting Jalili, whose vision dovetails with his own, against a representative of the reformist faction, which has proved more popular time and again?

The choice is particularly baffling considering that Khamenei had, in the past few years, finally achieved a long-standing dream: He had managed to fully populate the regime with hard-line zealots who paid him unquestioning obedience and shared his vision for an anti-West, anti-Israel, and anti-woman theocracy. In 2021, Ebrahim Raisi, a former hanging judge and an unimpressive lackey, was coronated president in an uncompetitive election.

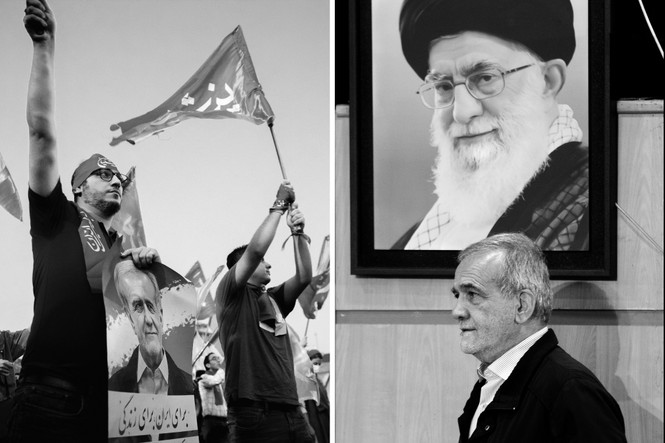

(Morteza Nikoubazl / NurPhoto / Getty; Saman / Middle East Images / AFP / Getty)

Before Raisi, every single one of the four presidents who served under Khamenei ended up becoming the leader’s political nemesis. Now Khamenei could say goodbye to all that. The Parliament, the judiciary, the Supreme National Security Council, and all the other major bodies of the regime, too, were dominated by conservatives and hard-liners in the Raisi era. Not only reformists, who had traditionally favored political liberalization, but even centrists, who adopted a pragmatic rather than ideological foreign policy, were booted out of positions of power. This past March, the Islamic Republic held probably its most restrictive parliamentary elections ever, a competition largely between conservatives and ultra-hard-liners. At long last, the 85-year-old Khamenei seemed to hold almost uncontested power.

So why would he jeopardize this state of affairs by allowing a reformist into the presidential race?

Khamenei has to be aware that the societal base for his regime is only shrinking. The mix of political repression and economic failure has proved unsurprisingly unpopular. A majority of Iranians refused to vote not only in this election but also in the three elections before it, starting in 2020. Even the reformists joined an official boycott this year, something normally more the province of young radicals and abroad-based opposition. Tens of thousands of Iranians turned out for street protests in 2017, 2019, and 2022–23, and hundreds were killed in violent crackdowns all over the country.

The regime put down those demonstrations, but its leaders have to know that they never addressed the problems that produced them. Millions of women continue to engage in acts of daily civil disobedience by refusing to abide by the mandatory-veiling policy. Prisons are filled with political detainees, including former regime officials such as Mostafa Tajzadeh, once a prominent reformist politician, and the well-known filmmaker Jafar Panahi. A terrible economy, poor growth, an ever-weakening currency, and skyrocketing inflation bedevil the country. Khamenei may well have calculated that if he doesn’t change tack, he’ll be due for no end of social explosions.

The regime’s international isolation may have also begun to feel untenable. Under President Raisi, Iran reestablished diplomatic ties with its historical foe Saudi Arabia and joined multilateral organizations such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Iran extended military aid and expanded ties with Moscow. But only a deal with the West can provide respite from the sanctions that are squeezing Iran’s economy. Even dealings with anti-Western countries, such as China, are hampered by those restrictions, which complicate all of Iran’s financial transactions. (On the campaign trail, Pezeshkian complained that China has demanded enormous discounts on oil as the price of doing business under the sanctions.) The Raisi administration held secret talks with the Biden administration, but they came to little. Now the possibility of Donald Trump’s return may be focusing Khamenei’s mind on this problem.

The regional situation surely also factored in. Iran’s shadow war with Israel, which turned to direct mutual attacks in April, is at risk of escalating, and Khamenei may feel that managing it will require subtlety. Fundamentalists like Jalili are great for grandstanding speeches—less so for delicate international negotiations. Here, too, West-facing figures—such as Javad Zarif, the former foreign minister who was Pezeshkian’s top aide during the campaign and is now the chair of his foreign-policy task force—once again have something to offer the Islamic Republic.

Raisi’s death in a strange helicopter crash on May 19 provided the opening for Khamenei to recalibrate his relationship with the reformists and centrists. Pezeshkian was disqualified from running for president in 2021. Earlier this year, he was denied even a parliamentary run; Khamenei then personally intervened to allow him to enter and win the race for the Tabriz seat he has held since 2008. For this presidential election, he was the only one of three reformist candidates to be approved.

That Pezeshkian got the nod over the others is not an accident. Having served as a health minister under former President Mohammad Khatami, Pezeshkian has strong reformist credentials. He has often led the minority reformist caucus in Parliament, and he gave a courageous speech in 2009 condemning the harsh repression of that year’s Green Movement. At the same time, however, he has demonstrated his loyalty to the Islamic Republic. In 2019, the Trump administration designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps a terrorist organization, and Pezeshkian, then the deputy speaker of Parliament, donned the militia’s green uniform for the cameras and proudly identified himself with it. That same year, he celebrated IRGC’s downing of an American drone.

As president-elect, Pezeshkian has already sought to reassure the regime’s traditional partners. He wrote a letter to the Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah promising continued support for the “resistance,” and he spoke by phone with Russian President Vladimir Putin to pledge continued ties. The Kremlin must be feeling a little antsy, given that many Iranian officials in the orbit of former centrist President Hassan Rouhani, including Zarif, have expressed open dislike for the regime’s recent break with Iran’s tradition of nonalignment in order to orient the country toward Moscow.

Despite being nominally a reformist, Pezeshkian did not campaign for any serious reforms this year. During the televised debates and on the campaign trail, he professed more fealty to the supreme leader than his hard-line rivals did. To compare this new reformist president with the reformists of two decades ago—Khatami and his coterie imagined marginalizing Khamenei and democratizing Iran—is frankly depressing. Pezeshkian ran as a technocratic centrist, very much like his major conservative rival, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, who, despite the support of much of the IRGC’s high staff, failed to garner more than 13.8 percent of the vote in the first round. Pezeshkian was endorsed by reformist grandees such as Khatami and the reformist cleric Mehdi Karroubi, who has been under house arrest since 2011. And yet, his campaign leads were mostly not reformists, but cabinet ministers from the centrist Rouhani administration.

Still, some of Pezeshkian’s personal qualities made him an attractive candidate, in a manner somewhat reminiscent of the hard-line populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad: Pezeshkian sports a humble, plebeian look—he often wears a raincoat instead of a suit jacket—and speaks in plain, straightforward language instead of the jargon typical of Iranian politics.

The previous time a reformist won the presidency—Khatami, in 1997 and 2001—he did so on the back of a major social movement. Rouhani, too, had a strong mandate behind him, which gave him ballast in confronting the establishment hard-liners when he needed to. Pezeshkian’s position is less secure, given last week’s anemic turnout, and the institutions around him are controlled by hard-liners. His fealty to Khamenei, and his lack of experience in high politics, might also make him a meek match for the grand ayatollah and his minions.

Pezeshkian will nonetheless be judged on at least three issues that dominated the campaign: whether he can help loosen enforcement of the compulsory hijab, relax restrictions on the internet, and, most important, effect an opening with the West that could help lift sanctions and improve the country’s economic outlook. On Saturday, which is the first day of the week in Iran, Tehran’s stock index jumped high, reflecting the market’s optimism about his prospects. But whether he can realize such hopes, especially given the limited power vested in Iran’s presidency, remains to be seen.

One wind blowing in Pezeshkian’s favor is the possibility of an alliance with some sections of the IRGC. He already has something of a tacit alliance with Qalibaf against the more extreme hard-line camp. Earlier this year, Pezeshkian’s support helped Qalibaf win the speakership of the Parliament. In the second round of the presidential elections, Qalibaf dutifully endorsed Jalili, as a fellow conservative, but he didn’t campaign for him, and many of his supporters endorsed Pezeshkian instead. Can this alliance extend into the Pezeshkian administration? And if so, how can the West-facing policy favored by Rouhani and Zarif be reconciled with the IRGC’s sponsorship of anti-Israel militias in the region, and the proximity of certain segments of the IRGC to Russia? It is a truism that a change in president won’t change Iran’s core policies, because these are set by Khamenei. But the ever-shifting balance of power among factions of the regime does have policy consequences.

Iran’s democratic and civic movements will have to decide how to navigate this rebirth of something like reform. During the election cycle, prominent activists and political prisoners were divided over whether to endorse Pezeshkian or call for boycotting the vote. Now they will need to plot their moves under his new government, weighing two competing impulses: to put demands on a possibly amenable administration, or call for the overthrow of the regime.

As for the octogenarian dictator, these waning years of his life resemble a Greek tragedy. Once a radical poet and a 1960s revolutionary who dreamed of building a better world, he has ended up overseeing a regime rife with corruption and incompetence, hated by most of its populace. Even many establishment figures know that revolutionary slogans won’t solve the country’s problems, hence their turn to technocracy.

Lenin once admonished that those who want obedience will get only obedient fools as followers. Khamenei never heeded that warning. Time and again, he pushed out independent-minded but impressive figures in favor of obedient fools. As he looks at the ragtag team of tinfoil-hat conspiracists and dour fundamentalists that surrounds him today, he must be somewhat embarrassed. Just five years ago, on the 40th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, he spoke of cultivating a government dominated by “devout young revolutionaries.” By opening up the political space to technocrats and centrists, he is perhaps admitting the defeat of that dream.

Arash Azizi is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and a senior lecturer in history and political science at Clemson University. His new book, What Iranians Want: Women, Life, Freedom, was published in January 2024.

Spread the word