How should unions engage with members drawn to right-wing, anti-worker politics and candidates? One union trying to tackle this disconnect is the Communications Workers (CWA).

Steve Lawton, former president of CWA Local 1102 in New York (now merged with Local 1101), has been heavily involved with political education through his work as a local leader and in the District 1 political department.

In this interview he discusses organizing in a union with many Trump-supporting members, how to talk with members about immigration, and strategies for organizing and building solidarity across political divides.

Katy Habr: You spent some time as the president of CWA Local 1102 in Staten Island. What was the political landscape of the local?

Steve Lawton: We had a local where 45 percent of the workers came from Verizon, which is where I came from. They were mostly white men. Over the 31 years I worked there, I watched them change politically. They went from being apolitical, maybe supporting the union’s political programs because they were strong supporters of the union and it’s what they thought they should do. About 60 percent of members even joined the Working Families Party and the union went to visit Occupy Wall Street.

But after a bad strike in 2011, they started to be discontented with the union and were less willing to accept the union’s political programs that they didn’t think were helping them.

Today they are probably 70 percent conservative-leaning, on a spectrum from really conservative right-wing to maybe conservative but pro-union to maybe even a conservative Democrat type.

Then 55 percent of the local was a group from EZ-Pass, newly organized call center workers. That group tended to be workers of color and mostly women, maybe 80 percent. I don’t know if they are Democrats or Republicans, but they were much more connected to things like paid sick leave and paid family leave. I could see the difference between these two constituencies in terms of politics.

How has it been trying to talk to people across these divides, and what do you think is the most effective way? Is it through trainings like “Runaway Inequality,” workplace action, or one-on-one conversation?

When Trump got elected, we were able to cross some bridges because we had an open, democratic organization, although we continued to push progressive politics like supporting the Black Lives Matter movement.

We allowed anyone to be a leader, no matter what their political views. We welcomed them and we gave them responsibility. We did not try to censor them. We held open and respectful general membership meetings where debate was allowed.

Some people are dug in on their ideas. But I like to think that people in the middle politically were open to having conversations.

We talk a lot about solidarity in the labor movement. Often U.S workers are pitted against immigrants and are told that immigrants are taking their jobs or it’s not in their interest to support immigrants’ rights. How do you have those conversations with people?

One of the things we did about immigration was we held a luncheon with undocumented workers and our core union leadership groups, which were mostly right-wing Republicans, in concert with the local worker center. And it was a great conversation.

What came out of it was that a lot of the members did not understand the plight of the undocumented workers in terms of why they’re not coming legally because they couldn’t afford it, the fact that they were here so long and had families, that they pay taxes—all those things really made them understand. Also hearing about the mistreatment that immigrants faced.

They agreed that people shouldn’t be picked up by an employer here on Staten Island, taken to a job in Pennsylvania, and be left there to have to walk home or get beaten up. These are some of the horror stories that these immigrant workers told. That really translated to our members. It was very fruitful.

I have an example of this guy Jeff, who is a total Trump supporter. I’ve known him a long time, so I’m able to engage with him. I remember one time during Covid-19, we did a huge event, an essential worker caravan that included undocumented immigrants with a worker center. The right-wing members were so pissed at us. Jeff comes at me saying “What are you doing? Immigrants!” This whole thing.

And I said, “I understand you have a hard, deep position on this, but let’s break it down. I’m not the politician who creates the policies. Whether or not we agree with the policy, I am not in charge of that. I’m also not the employer who hires these folks. There’s people that hire them. Do you agree with me? Does our society rely on undocumented workers?”

He goes “Yes—they shouldn’t. They should be held accountable for that too.”

I said, “Here I am, the labor leader in this community. You’re a worker. You might not see what I’m doing to support that worker as support for you. But the truth of the matter is, as a labor leader I’m not concerned with how they got here, I’m not concerned with why they’re here, and I’m not concerned with who’s hiring them. What I’m concerned with is the safety and welfare of every worker in this community.

“Because by looking at it from that angle, whether it be OSHA, whether it be wages, that affects you and affects all of us, right? If we allow workers to be mistreated by OSHA because they’re undocumented, doesn’t that affect your OSHA standards?”

And he got there. He was like, “You know, no one’s ever explained it to me this way.”

I said, “I’m not here for a political reason. I’m here simply because of solidarity and understanding that the principle of safety is one that we have to put across the board as labor.”

I was able to break through that way, and he calmed down and actually engaged in it and understood it. When they’re coming at you fired up with all the rhetoric that they’ve been pumped with, and the misinformation, you can’t engage with them with the way that they expect you to answer. That’s what they want. I try to remove that out of the equation first, and then bring it to where they are as a worker.

It seems like these one-on-one conversations really work. Can you tell me a bit about how that translates into a larger setting?

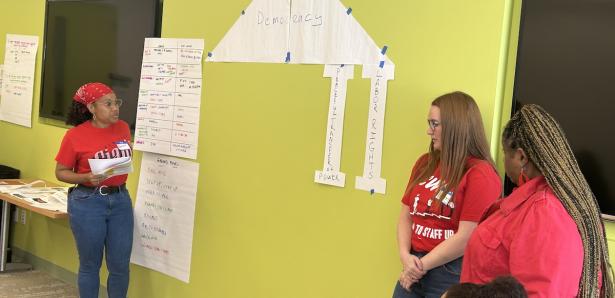

We’ve been developing this curriculum called Democracy Defenders. Immigration, inflation, and crime were the three issues that we put up. We’d go through the slideshow, and then we’d ask the groups to answer a prompt—something like a member saying: “What about all these illegal immigrants that are coming here and taking our jobs?”

The themes that we wanted to capture were: a) The migration problem was due to reasons that are outside of our control: poverty, violence, and ecological disaster; b) It’s happening globally, it’s not something that’s just here; c) Asylum seekers are not here illegally. We explained about asylum. And then we gave them a bunch of data points about the positivity of immigrant workers.

The second part of the training is how to have a one-on-one conversation. We did a thing called Organizing Theater where we model those conversations. We teach our organizers how to engage; to have that philosophy of meeting people where they are, not being judgmental, not engaging in in direct conflict.

You’re not here to win a competition or a debate. You’re here to try to move the conversation into something that you can connect on, or you’re looking to deescalate and get out of here. We make the point that some conversations aren’t worth having and gauging them is part of the job as the organizer.

We tell them, here’s some points that you can be making—not right away, but if you’re able to engage and open a conversation, then you can say, “Did you know about this point or this point?” We called it Identify, Educate, and Mobilize. Identify people who want to have conversations with you, educate them where you can, then mobilize them for actions.

So the purpose of the trainings isn’t so much to change everyone’s mind, but to train people how to have these one-on-ones where the change can happen?

We currently have a big problem. The political fights of the Trump years really beat up our front line, and a lot of union leaders have pulled back on political conversations. I think that’s a mistake. I think that we’re giving too much voice to too small of a group.

We need to start listening to our members that don’t fit the traditional framework. New members coming into the unions are much more progressive, more Black and Brown. I think they’re going to be more in line with policies like immigration reform. There’s a lot of opportunities in these newer groups for political power.

I think we need to teach our frontline members to break through the fear. We need to push forward mapping and having targeted conversations and building lists of people who support us. We never had 100 percent of the people doing political work for our unions. Let’s start building from this core who does agree.

Katy Habr is a former union researcher and Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Columbia University in New York City.

A version of this article appeared in Labor Notes Issue #546, September 2024. Don't miss an issue, subscribe today.

Spread the word