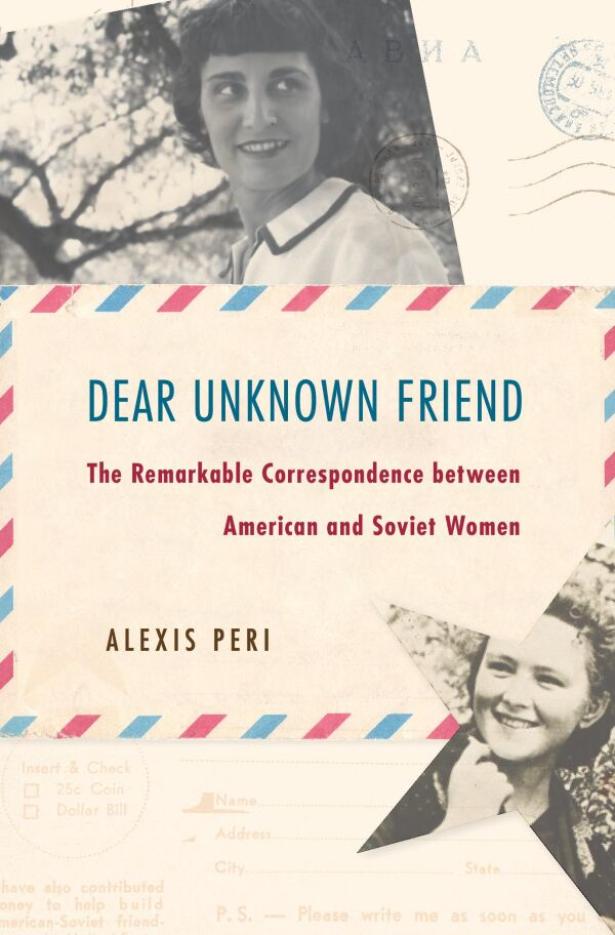

books Dear Unknown Friend: The Remarkable Correspondence Between American and Soviet Women

Dear Unknown Friend

The Remarkable Correspondence between American and Soviet Women

Alexis Peri

Harvard University Press

ISBN: 9780674987586

In September 1947, Myrtle Park, a 46-year-old housewife who raised cattle and wheat in Englewood, Kansas, sat down at her desk and began to write to an “Unknown Russian Friend.” In her letter, she wrote of her fervent desire for peace. “We believe that the USA and Russia can and should be friends,” she confided, “but our leaders, unfortunately, do not always express such confidence. They do not represent the interests of the common people of the United States.”

She concluded her letter, “I do so hope you, Russian people, may have the opportunity to go on with your way of doing things without ever having to fight another war. I am, sincerely your friend, Mrs. Ethan J. Park.”

A few months later, a response arrived from a Muscovite named Irina Aleksandrovna Kuznetsova:

“I was deeply touched by your interest to hear from far-away Moscow and the sincere sympathy that breathes in your letter. Those who have lived through the horrors of the last war cannot look with equanimity on preparations for a new war and cannot consider it other than the most horrible crime.”

To this, Park replied:

“I completely agree with you that war is the most horrible crime. I am determined that I shall do my little, tiny bit toward furthering understanding and peace on earth. World peace is based greatly on understanding, isn’t it?”

Park and Kuznetsova were just two of the 750 “ordinary” American and Soviet women who participated in a pen-pal program between 1943 and 1953 that sought to foster diplomacy and understanding between the two nations. This program is the subject of Alexis Peri’s Dear Unknown Friend, a highly readable and engaging history of a little-known aspect of Cold War history.

The correspondents, who held no government posts and had no foreign-relations experience, “thrust themselves onto the international political stage at a time when women were relegated to playing minor roles,” Peri explains. In the process of sharing the personal details of their lives, “they began to model what they believed was a new, woman’s style of diplomacy: a diplomacy of the heart. This was the idea that heartfelt storytelling and expressions of empathy could be mighty political forces, strong enough to help win wars and secure peace.”

The pen pals believed they would succeed in their peacemaking endeavors where official diplomacy had failed for two reasons. First, they were women, and women “were better than men at listening, forming friendships, and avoiding conflict,” writes Peri. And second, they believed they could be frank and open in their discussions because they were “common people,” not politicians. What the author finds in the letters is a “mixture of peacemaking and propagandizing.” While the writers were often genuine in their writing, they simultaneously “performed what, in their eyes, it meant to be a citizen, woman, worker, mother, and peace advocate in the United States or Soviet Union.”

One of the most remarkable aspects of the pen-pal project was that it “upends the conventional historical wisdom that there was virtually no contact between American and Soviet citizens during the Truman-Stalin era.” In fact, like many historians, Peri believed that “communication between American and Soviet civilians began to flow only after Stalin died in 1953 and when President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Premier Nikita Khrushchev tried to ‘thaw’ relations between their countries.” It was when Peri was conducting research on another project that she discovered the letters, “hastily bundled together and gathering dust in the State Archive of the Russian Federation.” Her project casts a light on this virtually unknown chapter in U.S.-Soviet relations.

Women wrote not just about politics and war but also about their personal experiences as wives, mothers, workers, and other identity categories to which they belonged. Interestingly, though, the American and Russian letter writers stressed different aspects of their identities. Explains Peri:

“The Americans began by describing their marital status, children, and living conditions in that order of priority, whereas their Soviet interlocutors stressed their educations and occupations. Some…did not mention family life until a second or third letter. Conversely, American letter writers often did not indicate their level of education until well into the correspondence.”

The letters shed light on correspondents’ priorities and self-perception, says Peri, and also served to challenge and correct cultural labels:

“The letters cut against emerging cold war stereotypes that Soviet women were so haggard and overworked that they had little time or energy for their children, and that American women were so absorbed in homemaking that they did not look far past their manicured lawns or local parent-teacher associations to make larger contributions to society. In fact, the vast majority of the American and Soviet correspondents understood ‘women’s work’ to mean some combination of the domestic and the professional.”

In other words, women were discussing the challenges of “having it all” even before this topic came to the forefront of feminist conversation. Though the letter writers “did not identify as feminist activists,” Peri stresses that their explorations of their roles as women served as an important precursor to the feminist movements that followed:

“Pen friendship…helped raise the letter writers’ consciousness of what was possible for them to achieve as women and what constraints prevented them from realizing their potential. Such awareness was integral to the women’s liberation movements, which crystalized in the United States during the late 1960s and in the Soviet Union during the 1980s. Many (especially middle-class) women in the United States…pushed for more professional and educational opportunities, whereas women in the Soviet Union often sought greater freedom to spend more time at home…Equal wages, steady employment, and access to childcare and contraception were major demands of both movements.”

When the letter-writing program started during World War II, the USSR and United States were political allies and had reason to foster friendship and understanding between their peoples. However, in the postwar period, as tensions between the countries escalated, the program came under scrutiny until, says Peri, “corresponding for American-Soviet friendship was increasingly looked upon as an act of subversion, not of patriotism.” While each letter had always been reviewed by authorities on both sides — passing through at least four sets of hands between the time it was written and the time it reached its intended recipient — in the late 1940s and early 1950s, participants began to feel pressure to stop writing (and many did).

Those who continued, like Gladys M. Kimple of Friday Harbor, Washington, recognized they were taking a risk, since American mail going to the USSR was now being inspected by the CIA. “Aware she was under surveillance, Kimple began censoring her remarks but did not hide her disdain for new, uninvited readers,” Peri reports. “As the campaigns against communism intensified, she wrote more frequently and defiantly.”

In the end, Peri notes, Kimple’s “family paid a high price for her involvement.” Not only was her brother-in-law “hauled before the Weld Committee on Un-American Activities,” but her son was “honorably discharged” from the U.S. Air Force and lost his license to fly. “Translated into everyday language,” Kimple explained in one of her letters, “it means that because of mine — not his — beliefs he is considered insufficiently trustworthy for military service.”

With officials in both countries dubious of the program’s benefits, it was eventually discontinued, but its impact, though modest, is noteworthy. The “diplomacy of the heart” that a small group of American and Russian women practiced for a decade can teach us something even today. Peri writes:

“It was based on the notion that during times of war, hot or cold, being emotionally open, empathetic, and even vulnerable could be politically expedient rather than pose a political liability. The pen pals frequently argued points of view that aligned with those of hardline politicians. The difference was they wrapped their disagreements in a mantle of shared humanity and common concern. They altered the method, not the message. And this enabled them to write through disputes and misunderstandings and to exchange dozens of letters during an era when official diplomacy between the United States and the Soviet Union was often at an impasse.”

I find Peri’s book fascinating for personal reasons, as well. My Russian mother and American father met in the Soviet Union in the mid-1970s, at another juncture of the Cold War, and I was born there but grew up in the United States in a bilingual home. Though my two grandmothers, who were both having children during and immediately after World War II, were not part of the pen-pal program, they were the ages of many of the correspondents, and in reading the personal accounts of the American and Soviet women as they navigated motherhood, household duties, work, politics, and other concerns, I was able to see something of my grandmothers’ experiences and attitudes reflected in the words of other women. The pen pals speak as much for their cohorts as they do for themselves.

But even without a personal connection, this book is a worthy read, sure to appeal to anyone interested in Cold War history, women’s history, or the feminist movement. Peri writes in an engaging and accessible style; this is not a dry, formidable tome but rather a lively volume that keeps its focus on individual lives and stories. Carefully researched, Peri’s work does much to place the women she’s studying within historical and political contexts, and she has gone beyond archival documents to contact descendants of the women to discover what became of the letter writers and whether their pen-pal activities had a lasting impact on them. (Peri’s research on this latter question is inconclusive; she notably had much more luck in tracking down American descendants than Russian ones.)

Though few in number, the women who wrote to one another from 1943-53 were “part of a groundswell of new attitudes about women’s rights and about the power of citizens to prevent war.” As Peri notes, “We can see history flow through them. Their conversations created ripples, and those ripples streamed into the currents of thought that helped define an age.”

Yelizaveta P. Renfro is the author of a book of nonfiction, Xylotheque: Essays, and a collection of short stories, A Catalogue of Everything in the World. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Glimmer Train Stories, Creative Nonfiction, North American Review, Colorado Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, South Dakota Review, Witness, Reader’s Digest, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from George Mason University and a Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska.

Spread the word