Note: On February 7, Trump announced that he was taking over the Kennedy Center in Washington DC. Not surprising, controlling the arts that has long been a dream of reaction. This calls to mind the ban Hitler imposed on literary criticism — an anti-Semitic measure (Jews can “critique but cannot create” was a trope repeated in various forms ad nauseum in those years) to be sure. But it also exemplified the essence of the fascist approach to art: if it is not immediately comprehensible, then it is subversive. Put in other terms, critical thinking is itself subversive. The manifestations of that are visible everywhere today, most vividly in renewed book bannings, rewritten school curricula, repression of sexuality (which fits nicely with permissiveness toward sexual assault) and, of course, suppression of critical race theory (that word, “critical,” does it every time).

By contrast, anti-fascist films, anti-fascist art in all its forms, has one prime purpose: to encourage critical thinking, see beneath the surface, understand life in movement. The recent film about the assassination of Lumumba — Soundtrack of a Coup d’Etat — reminds us of the connection between fascism and colonialism and reminds us of the centrality of culture in the fight for freedom. Thoughts to keep in mind while watching the films noted below.

Introduction

We are entering into a new period of reaction – and though the exact shape things will take in the years ahead are unknown, the immediate picture is indeed bleak. We face the all too real risk of authoritarian reaction, unfettered corporate power, a society rooted in stigmatization, violence, the crumbling of hard-fought rights. It is not too much of a leap to recognize the danger of fascism.

Critically, what we do matters. How we live, act, make a life for ourselves without giving in to resignation or bitterness are questions many are asking. Many movies have explored these dimensions for these are questions others have faced in times past – such as the films noted below — all anti-fascist movies that reveal different aspects of how people have seen the possibility of change in the past during times when hope was hard to grasp. Below is a list of 28 such movies.

These films don’t directly analyze the social or economic basis of fascism, nor do they dwell on its horrors (though those are never far from the surface) for what is most important is not what people with unbridled power can impose on us, but rather on what we can do as human beings, as political actors.

A fuller description of these films and the logic behind choosing them can be found here.

Hope and Fear

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?: A German film released and banned in Germany in 1932. Directed by: Slatan Dudow; Written by: Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ostwald

To understand fascism, one needs to understand what preceded it. The devastation of World War I, economic uncertainty, inflation, massive unemployment, intense exploitation at work, and a sense of society coming apart at the seams were in the background of all the disruptions of the 1920s and 30s. But so too was the defeat of working-class challenges to the rule of capital. In Central Europe the strength of revolutionary movements was palpable, but insufficient, creating fear in ruling circles, yet not strong enough to overcome the attacks that were to come. These films explore aspects of those hopes and defeats.

Rosa Luxemburg – Directed by Margarethe Von Trotta (West Germany, 1986). Luxemburg’s life culminates in opposition to World War I, her leadership of a revolutionary movement in the working class, its suppression, and her brutal murder at the hands of the forerunners of Hitler’s stormtroopers.

The Organizer (I compagni) – Directed by Mario Monicelli (Italy, 1963). A depiction of a mass strike, followed by an attempt to occupy factories, met by brutal armed suppression. A pre-World War I battle foreshadowing the larger post-war factory occupations which was followed by Mussolini’s March of Rome and the suppression of labor.

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World (Kuhle Wampe oder: Wem gehort die Welt?) – Directed by Slatan Dudow (Weimar Germany,1933). Screenplay by Bertolt Brecht. Filmed on the eve of the Nazis takeover, it depicts the misery of mass unemployment in the waning days of the Weimar Republic. In counterpoint, it shows Communist youth trying to create something for themselves through mutual support, a sense of collectivity, through confidence in political struggle.

La Vie est a Nous (Life is Us) – Directed by Jean Renoir (France, 1936). A French Communist Party film mixes narrative with documentary made to support the Popular Front election campaign in 1936.

Eve of Destruction

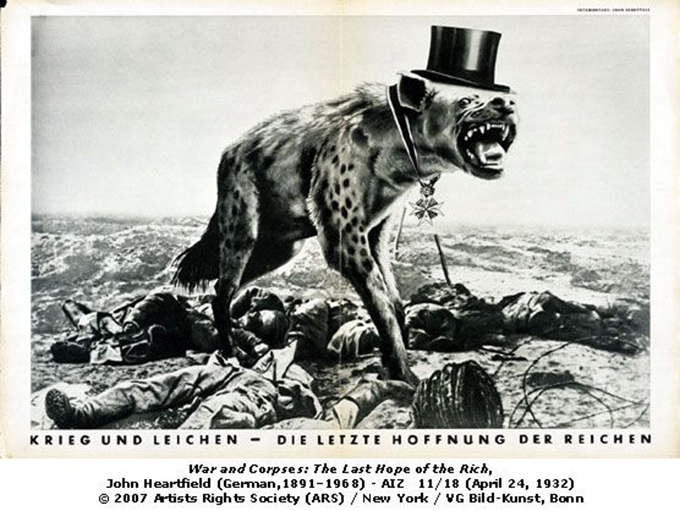

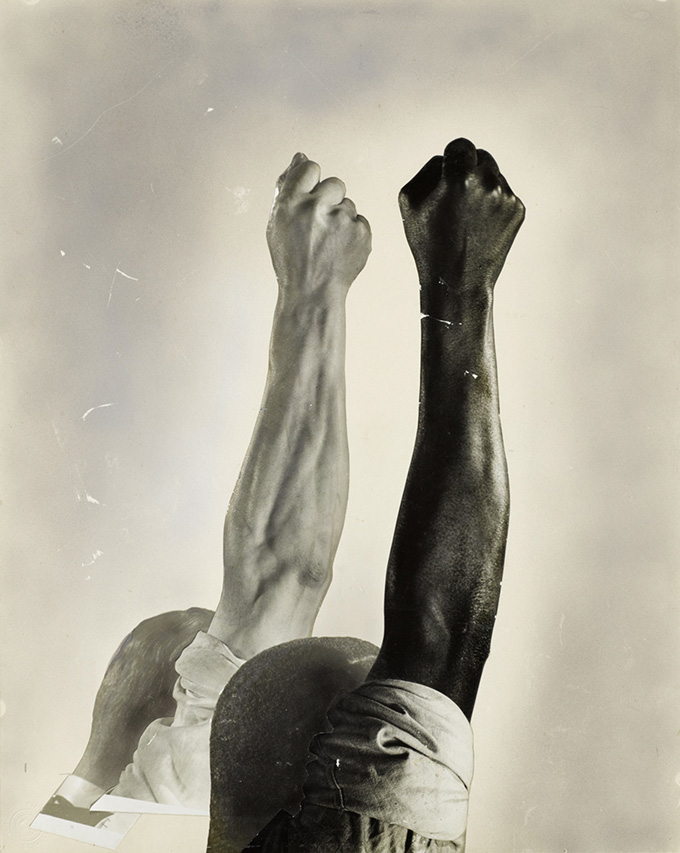

John Heartfield - a pioneer of the photomontage, he worked in Germany and Czechoslovakia between World War 1 and 2. He was a preeminent political artist using his skills to comment and attack the rise of fascism, the Nazi and their relationship with capitalism.

Fascism cannot be separated from periods of instability and crisis in capitalist society. But to say that and no more says very little – why such a virulent response at one time and not another, what does it mean to live in a society on the edge? More to the point, how do we understand why some people look backward not forward as a way out? The following films are attempts at answers.

Der Untertan – Directed by Wolfgang Staudte (East Germany, 1951). Based on a novel by Heinrich Mann. A satire of the middle-class personality who licks the boots of those in power above them while kicking those below them – i.e. the personality type who gravitated to the Nazis.

The Conformist (Il Conformista) – Directed by Bernado Bertolucci (Italy, 1970). An examination of the authoritarian personality; someone whose search to “fit in” includes an unquestioning willingness to kill. Alberto Moravia’s novel about the murder of two anti-fascists in French exile inspired the film.

Ship of Fools – Directed by Stanley Kramer (U.S., 1965). Screenplay by Abby Mann. Based on a novel by Katherine Anne Porter. An ocean liner enroute from Mexico to 1933 Germany evokes the sense of oncoming disaster from the interactions of passengers who are – for the most part – unaware of what lies ahead.

Cabaret – Directed by Bob Fosse (U.S. 1972). Set in and around a musical hall in Berlin on the eve of fascism’s triumph with performances taking place in an atmosphere of despair and forced gaiety. The sensibility of a society coming apart at the seams is told through the eyes of a gay academic teaching English at a boarding house to earn his keep. Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories are the basis of the film.

Living Under the Grip

John Heartfield

Lives continued to be lived in the worst of times. These films all depict daily life and the way political commitment and forms of resistance sometimes emerge when the realities of war or repression can no longer be ignored.

Christ Stopped at Eboli (Cristo si è fermato a Eboli)– Directed by Francesco Rossi (Italy, 1979). Carlo Levi’s memoir of internal exile in a barren impoverished region of southern Italy is gives a view of fascism far from the cities or centers of power that are the focus of most accounts. The film captures the life he relates beautifully.

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis ( Il giardino dei Finzi Contini) – Directed by Vittori DeSica (Italy, 1970). Based on Giorgio Bassanti’s semi-autobiographical novel. The story of the tightening noose of a small wealthy Jewish community that had initially been insulated from Mussolini’s repressive policies.

The Seventh Cross – Directed by Fred Zinneman (U.S., 1944). Seven concentration camp inmates escape, one survives. He regains his sense of humanity, while the individuals, as do the individuals who help him along the way – providing a connection to political resistance. Anna Seghers wrote the novel while in exile in Mexico.

Alone in Berlin by Directed by Vincent Perez (Germany/France/UK, 2016). The film brings to life Hans Fallada’s novel of a true story of a working-class couple, animated by their son’s death in combat and the persecution of a Jewish neighbor to engage in their own, personal, resistance. A campaign they carried out until their own execution.

Resistance to Fascism’s Wars

John Heartfield - “Krieg! (Niemals wieder!)” Silbergelatineabzug mit Pinselretusche, 1932/1941 © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020 / Akademie der Künste, Berlin

War brought out the full brutality of fascism. These movies were all made during wartime or when memories were still fresh. They all touch on conflicting urges to ignore, collaborate or resist, and with that the personal choice whether and how to act, to survive with humanity intact.

Blockade – Directed by William Dieterle (U.S. 1938). Screenplay by John Howard Lawson. Film centers on the attempt to break a blockade to get supplies in to support Spanish Republicans resisting Franco. It serves as a plea to end U.S./British/French non-intervention policies.

This Land is Mine – Directed by Jean Renoir (U.S., 1943). Two schoolteachers in occupied France are the focal point of a story of resistance and collaboration, courage and fear.

Hangmen Also Die – Directed by Fritz Lang (U.S., 1943). Screenplay by Bertolt Brecht. Resistance in occupied Czechoslovakia in the aftermath of the assassination of SS leader Heydrich.

Open City (Roma città aperta) – Directed by Roberto Rossellini (Italy, 1945). The resistance as Mussolini’s rule is near its end, brutal repression, a search for Communist/Catholic unity for an alternative future.

The Fate of a Man – Directed by Sergei Bonarchul (Soviet Union, 1959). Based on a short story by Mikhail Sholokhov. The journey through life and loss of a Soviet soldier that sketches Nazi wrought destruction and the search for human bonds and hope in the war’s aftermath.

Lifeboat – Directed by Alfred Hitchcock (U.S., 1944). Based on short story by John Steinbeck. Set on a lifeboat filled with a heterogenous number of survivors of a torpedoed merchant ship and one Nazi rescued from a submarine, the movie presents a contest between democratic multiplicity and authoritarian single-minded power.

Coming to Grips With the Past

After the war comes the battle for understanding – what happened, how did people behave? And how does that inform choices we are making here and now so that other, better, choices may be possible later

Judgement at Nuremberg – Directed by Stanley Kramer (U.S. 1961). Screenplay by Abby Mann. The Nuremberg tirals were an attempt to establish criteria for crimes against humanity. This film recounts the story of judge’s whose compromises with the truth corrupted the law, corrupted society.

The Nasty Girl – Directed by Michael Verhoeven (West Germany, 1990). A high school student who challenged her town’s sanitized version of the past, revealing its complicity with the Nazis. A true story, the film reveals the hypocrisy in many German treatments of fascism.

Playing for Time – TV movie directed by Daniel Mann (U.S., 1980). Screenplay by Arthur Miller, based on memoir by Fania Fenelon’s memoir about Auschwitz and her being “allowed” to survive because recognized as a classical musician. An orchestra formed of inmates to perform for SS officers one aspect of Nazi perversity as against the will to survive of those they caged.

Life is Beautiful (La vita è bella) – Directed by Roberto Benigni (Italy, 1997). A story about how telling stories, conjuring the imagination, is a way to survive the most brutal conditions, story-telling an essential part of resistance to oppression.

Jacob the Liar (Jakob der Lügner)– Directed by Frank Beyer (East Germany, 1975). Living in the Warsaw Ghetto as the noose was tightening, a man hears that Soviet troops are nearing the border. He tells others, giving hope where there was none, and then makes up stories to try and keep hope alive.

Fascism: Other Times, Other Places

The films noted above, focus on Germany and Italy in the 1930s and 40s because that is the main reference point for fascists and anti-fascists in our own country. But fascism has existed at other times, in other places and these too should be noted. Below are just a very few of the many possible films that serve to remind that the dangers facing the world now are part of a continuum that someday needs to be overcome at its roots.

Z – Directed by Costa-Gravas (France, 1969). About 1967 coup in Greece, based on Vassillis Vassilikos fictionalized account of the Greek’s military’s role in the 1963 assassination of Giorgios Lambrakis.

Burning Patience (Ardiente paciente) – Directed by Antonio Skarmeta (Chile, 1985). Skarmeta, also wrote the screenplay and the novel of that name. The film is about a postman incurably in love, poetry, events in Chile leading up to Pinochet’s fascist coup – and is about Pablo Neruda.

Argentina, 1985 –Directed by Santiago Mitre (Argentina, 2022). Recounts the trial of the leaders of Argentina’s military junta, for the extra-legal murders and tortures that took place during the “dirty war,” in which tens of thousands were killed by government decree

Cry, The Beloved Country – Directed by Zoltan Korda (UK, 1951). Screenplay by John Howard Lawson, based on novel by Alan Paton providing a glimpse of South Africa as apartheid was bing imposed on a society that was legally and structurally racist. Filmed on location, so stars Canada Lee and Sydny Poitier had to pretend to be Director Korda’s indentured servants.

A Dry White Season – Directed by Euzhan Palcy (U.S. 1989). Based on a novel by Andre Brink, the film demonstrates how South Africa’s apartheid was its own form of fascism.

Kurt Stand was active in the labor movement for over 20 years including as the elected North American Regional Secretary of the International Union of Food and Allied Workers until 1997. He is a member of the Prince George’s County Branch of Metro DC DSA, and periodically writes for the Washington Socialist, Socialist Forum, and other left publications. He serves as a Portside Labor Moderator, and is active within the reentry community of formerly incarcerated people. Kurt Stand lives in Greenbelt, MD.

Spread the word