Normally, I don’t believe in confidence.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, “confidence” was the first refuge of scoundrels. That is, the supposed need to retain or restore confidence was constantly invoked as a reason to pursue destructive policies. If you argued for adequate stimulus to fight the Great Recession, you were told that this would undermine confidence. If you argued against austerity that would block economic recovery, you were told that slashing spending would actually boost the economy, because it would inspire confidence — a claim I mocked as belief in the “confidence fairy.”

The truth is that most of the time you should evaluate economic policies based on what they actually do, not with speculation about how you imagine they will affect confidence.

But this isn’t most of the time. This is the third year of the second Trump presidency — OK, it’s actually only part way through the third month, but it feels like years. And Trump is in the process of showing that a sufficiently chaotic and incompetent government can, in fact, do enough damage to confidence to inflict serious economic harm.

The most telling indicator here isn’t the plunging stock market — Paul Samuelson’s old jibe about the market having predicted nine of the last five recessions still applies. It is, instead, the plunging value of the dollar:

Source: xe.com

Standard economic analysis says that tariffs strengthen a nation’s currency. If the United States puts taxes on imports, this discourages businesses and consumers from buying foreign goods, which reduces the supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market and should drive the value of the dollar up.

In fact, the normal effect of tariffs on the exchange rate was one of the reasons to doubt that the Trump tariffs would help U.S. manufacturing: A stronger dollar would make U.S. producers less competitive, offsetting the protective effects of the tariffs. And as you can see in the chart above, investors drove the dollar up after Trump’s election win, partly because they believed that tariffs would have their usual effect.

But the dollar fell once investors began to see Trump policy in action. Permanent tariffs are bad for the economy, but businesses can, for the most part, find a way to live with them. What business can’t deal with is a regime under which trade policy reflects the whims of a mad king, where nobody knows what tariffs will be next week, let alone over the next five years. Are these tariffs going to be permanent? Are they a negotiating ploy? The administration can’t even get its talking points straight, with top officials saying that tariffs aren’t up for negotiation only to be undercut by Trump a few hours later.

Under these conditions, how is a business supposed to make investments, or any kind of long-term commitment? Everyone is going to sit on their hands, waiting for clarity that may never come.

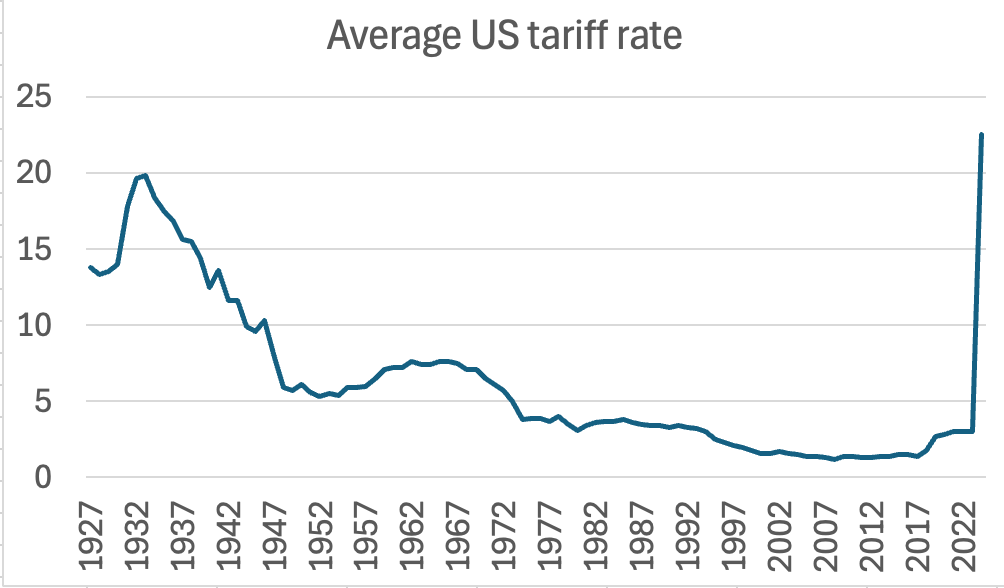

Wait, it gets worse. You might have expected a lot of careful thought to go into the biggest change in U.S. trade policy since the republic was founded:

But since Trump delivered his Rose Garden remarks, we’ve had a series of revelations about how slapdash and amateurish an operation this was. Trump declared that he was imposing tariffs on nations “that treat us badly”:

e will calculate the combined rate of all their tariffs, non-monetary barriers, and other forms of cheating.

But we soon learned that no such calculation had taken place. Trump’s tariffs were, instead, determined by a crude, and, well, stupid formula that made no economic sense. It’s still an open question whether that formula was determined by some junior staffer or derived from ChatGPT and Grok.

Maybe the next movie in the Terminator franchise will be “Terminator: Trade War,” in which Skynet realizes that it doesn’t have to destroy humanity with nuclear bombs, it can accomplish its goals simply by giving bad economic advice.

An aside: Did anyone think about how to enforce wildly different tariffs on different countries, when it would be easy to transship goods? The Republic of Ireland, which is part of the European Union, is supposed to face a 20 percent tariff, while Northern Ireland, part of Britain, faces only a 10 percent rate. So can Irish exporters cut their tariffs in half by shipping goods out of Belfast? Will there be elaborate rules of origin to prevent this? And who will devise and enforce these rules?

Actually, I’m pretty sure I know the answer to my question: No, nobody thought about that, because there wasn’t time. The Wall Street Journal reports that the White House didn’t even settle on the idea of country-specific tariffs until the day before the big announcement.

Again, the biggest trade policy change in history, hastily and sloppily thrown together at the last minute.

It’s no wonder, then, that confidence has taken a big hit. If you ask me, however, I’d say that confidence is still too high: business still hasn’t grasped how bad things are. For while tariffs are dominating the news right now, they’re part of a broader pattern of malignant stupidity. It may take a while before we see the effects of DOGE’s destruction of the government’s administrative capacity, or RFK Jr.’s destruction of health policy, but we will see those effects eventually.

And Republicans have just confirmed Dr. Oz to run Medicare and Medicaid. What could go wrong?

Personally, I’m feeling very confident. That is, I have high confidence in predicting that we’re heading for multiple policy trade wrecks, inflicting damage like you’ve never seen before.

I [Paul Krugman) am an economist by training, and still a college professor; my major appointments, with some interim breaks, were at MIT from 1980 to 2000, Princeton from 2000 to 2015, and since 2015 at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. I won 3rd prize in the local Optimist’s club oratorical contest when in high school; also a Nobel Prize in 2008 for my research on international trade and economic geography.

However, most people probably know me for my side gig as a New York Times opinion writer from 2000 to 2024. I left the Times in December 2024, and have mostly been writing here since.

Subscribe or upgrade subscription to Paul Krugman's Substack column.

Spread the word