“We organize first and foremost, so we can live, and second of all so we can live well,” writes visual artist and organizer Ricardo Levins Morales in his first book, The Land Knows the Way: Eco-Social Insights for Liberation. It is an ambitious tome for the social movement organizers, activists, and artists of our time who are seeking to unite the global working class against the many interlocking, spiraling systems of oppression that are exploiting people and the planet.

You won’t find specific answers, solutions, or roadmaps to the many challenges we face today, but you will find strategies, tactics, and organizing tools rooted in history and memory that can help shift the narratives in our everyday lives. An organizing manual that is also memoir, you can flip to any page of this poetic, meditative, and meandering text and find an exploration of the questions, What is solidarity? What is liberation? What does the land have to do with all of this? “Sometimes, meandering is the point,” says Levins Morales.

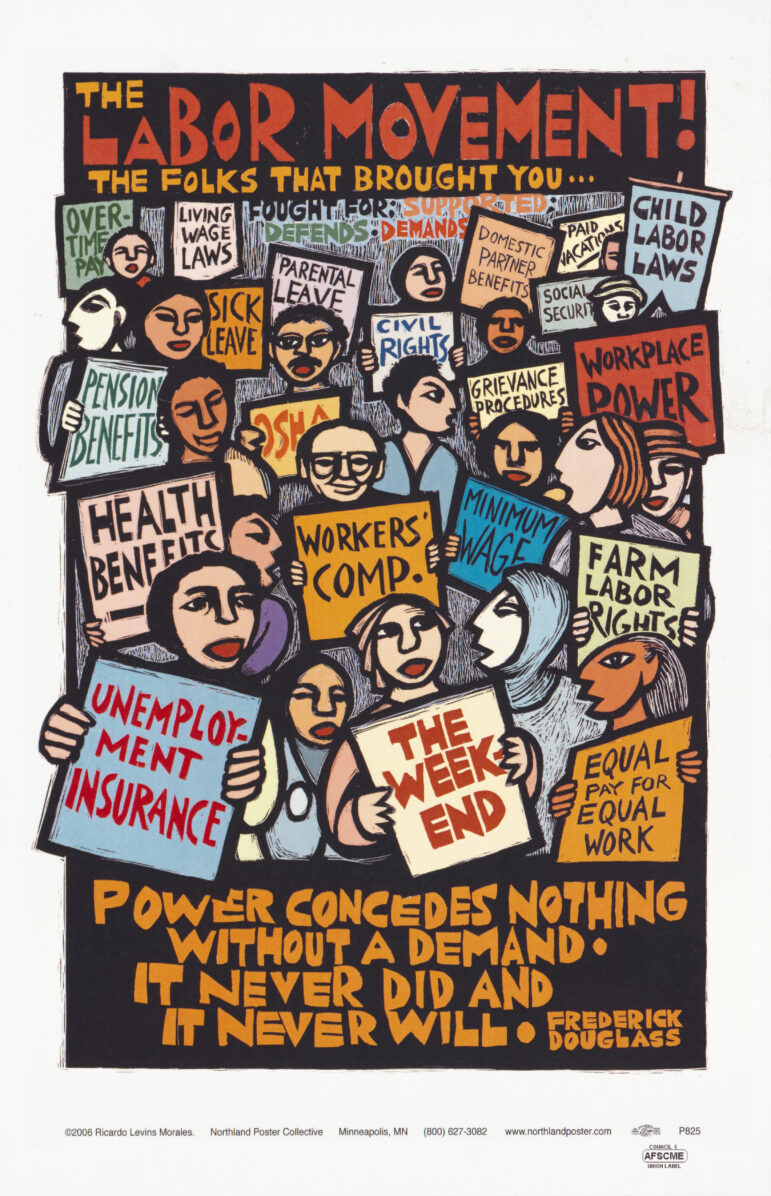

Born in Puerto Rico and hailing from an activist family that moved to Chicago in the 1960s, Levins Morales left high school early. He began working in several industries and started to make art devoted to building social and political consciousness. His work has supported farmers and activists such as the Black Panthers and Young Lords, as well as environmental, labor, racial justice, and abolitionist movements. In 1979, he helped found the Northland Poster Collective, a grassroots silkscreen print shop and poster distribution center that operated in South Minneapolis for 30 years.

The Northland Digitization Project has been working on the Northland Poster Collective Archive, which includes art and oral histories. Ricardo Levins Morales, “The Labor Movement,” Northland Poster Collective Archive, accessed August 21, 2025, https://omeka.northlandpostercollectivearchive.org/items/show/255.

In the past five years of reporting on workers and their struggles, I’ve learned how his work, especially his Tending the Soil zine, has had a prominent role in helping to build a more inclusive visual language and solidarity. In his book, he mirrors a critical and honest analysis of the history of our political and economic systems with his personal history of scrappiness and creativity, survival and resilience. Far from romanticizing suffering and loss, Levins Morales shows us that change, or adaptation through hardship, is an essential part of creating healthy soil that grows movements.

More than 300 pages, the book’s lessons are easy to consume, and reading it feels like talking to your favorite teacher or neighbor. Levins Morales says he is working on an audiobook version.

“I wanted to be able to invite hard-nosed shop floor organizers, veterans of labor battles, with people whose pathway into activism is through spirituality, or people who have come in through adrienne maree brown’s emergent strategy, people from different narrative streams who are comfortable in different ways,” says Levins Morales. “I wanted to throw in enough hints that if you keep reading, I see you, I know you’re here, I have some treats for you.”

Workday Magazine sat down with Levins Morales at his studio in South Minneapolis on a warm, summer day, to talk about his journey making this book, the power of art and stories, and our current moment of social and political consciousness. The following interview was edited for clarity and length.

Workday Magazine: Thank you for writing The Land Knows the Way. Who is this book for?

Ricardo Levins Morales: The most important strata of folks are the people who themselves have constituencies, whether they’re artists or teachers or leaders or shamans. People who are in a position to disseminate. It’s partly “healer, heal thyself.” If one of the big underlying conditions in the culture is a kind of hopelessness, you can’t spread a positive vision that stimulates hope if you don’t feel hope yourself. So partly, this is a way to shift some perspectives, both in analysis and in emotional chemistry, for all of these people who are the people who organize, who preach, who teach.

Workday: That term, “emotional chemistry,” stuck out to me. How do we change the emotional chemistry of community and movements? I think of the metaphor of the soil, and how you point out that conservative think tanks and politicians have prepared the soil for generations that we’re in right now. They’ve exploited the emotional chemistry that we have, the panic and the fear.

Levins Morales: As somebody who came of age in a time when there were radical movements, I’ve always looked skeptically at the blurring of the lines between radical and liberal. You have a dominant liberal narrative, which is, “We need to secure our borders, just not that way. We need more police, just not quite as mean. Corporations are over-regulated, just not as much as the Republicans say.” It’s not a compelling counter argument.

Workday: It’s not. Does it matter what seeds you’re planting if the soil isn’t healthy?

Levins Morales: The right wing accuses the Democrats, extreme radical Marxists that they are, of wanting open borders. Well, what would open borders mean? It would mean friends of mine who came here and got stuck here would have been able to come here and then go back to their families. It would mean that they’d have to raise wages in Mexico in order to keep workers. They wouldn’t have this two-tier wage system here because of people’s vulnerability. If you’re worried about criminals and smugglers and drug dealers crossing the desert, make it legal to cross at checkpoints for everybody. Then the only people who are crossing the desert are the people who have something to hide. I mean, it’s just shifting the narrative in ways that can’t even get a wedge into the conversation among the main people who hold sway in the public square.

Workday: There’s so much logic to shifting these narratives! The book is filled with how to do that. I would love to know more about the writing and editing process. How did you decide what to include?

Levins Morales: One of the ways I decided what to include is by running out of time. When I came to the realization that sometimes people actually finish books, I realized I would have to put a stop on it. So there are multiple sections that are partly written or started that I just had to drop. I had this crazy idea that I was going to try to get it out by the election. So I kind of rushed some of the editing and proofreading process, but ended up not coming out then anyway, so there was an unnecessary hurry based on a false urgency. I should have read my own writing. The writing process started out with intermittent time spent really writing the thoughts, writing down explanations. But I didn’t have a voice, I didn’t have a rhythm. I wasn’t sure how to do it. I’m not an academic. I didn’t want to imitate the authority on high telling you how things are.

Four or five years ago, someone who had walked into my shop once and had a conversation approached me at a public event and said, “Do you want to be writing accountabili-buddies?” I’d never heard of it before. Elle, who’s in the acknowledgments, is a playwright, and we would meet once a week over a cup of coffee. I’m an introvert, which means that I don’t generally share half-done things I wanted polished, but this was really lovely to be able to share that level of raw stuff that’s in process. I hired a local editor, hired a proofreader, and I found an indexer who was very excited at the content of the book, who’s down with liberation, who came up with a great index.

Workday: You write about learning how to read the landscape. Why open the book with that?

Levins Morales: There was a time when I was working with groups, working with organizers, sharing some of these ideas. And some people would attend these events and say that they made their head explode. Then the next day they’d go back to work and still not know what to do. There was no clear way to translate between that and their to-do list, all the calls they needed to make and the logistics they needed to arrange. So I started trying to morph it more in a way that it’s not a prescription of what to do, because there is none, but as people absorb it, it gives more of a sense of guidance. Highlights some of the dilemmas that people face, and tries to demystify them so that it wouldn’t be just back to the grind.

Workday: You write about how organizers and revolutionaries have thought differently about how to reach the audiences that they need to reach. There’s so much that artists can do on that end because they can speak to a larger audience.

Levins Morales: And organizers who learn how to speak in artistic terms. I don’t know if you’ve heard my snarkiness about the two kinds of organizing—the kind that puts narrative and story at the heart of organizing, at the tactical, strategic and vision level, and then there’s the kind that hasn’t figured it out yet.

Workday: One of the most impactful chapters for me is the one on tide pools. The section on living through moments with huge protests happening and more people wanting to be plugged in. Do you think we’re in one of those moments right now?

Levins Morales: I find myself, a lot of the time, trying to convince people that the moment that we’re in isn’t the way it’s always going to be, when the tide is out. Yes, movements will return when the tide is in. This is not going to last forever. In fact, we’ve gone through several of those since I started writing this book. The George Floyd uprising brought people into the streets who had never been in the streets before. Most of those people, given the scale, all these little white towns marching for Black lives, means that some of the changes in consciousness are real, but the people have nowhere to go. They don’t know what to do, they don’t have experience, they don’t have organizational structure. They’re waiting for opportunities that will once again engage them and allow them to do something with what they now feel deeply about and what just happened.

Workday: I started reporting on workers in the fall of 2020, after the uprising. And a lot of the organizing that was happening was workers saying, “We were in the streets, and nothing really changed. So we have to go into the places where we spend most of our lives and change things through unionizing or other organizing efforts.” So much resulted from that, and the violence that caused that. And especially right now, it’s such a scary and hard moment, and there are so many connections and so much community being made, right?

Levins Morales: One of the few silver linings of fascism is that they attack everyone at once. Solidarity starts looking like an attractive option. We’re seeing more and more people stepping forward with real passion and commitment in defense of communities that they’re not a part of, starting to see those connections in a way that have not been front and center for a long time.

The workers of RLM Art Studio, located in South Minneapolis, are represented by the Newspaper and Communications Guild/CWA. Photo by Amie Stager.

Workday: You take us on journeys through space, from microscopic communication between the cells in our bodies to global patterns of extinction and resistance. Then you take us through time, including deep time and ancient history all the way up to recent memory. And through it all, the story of planet Earth as ultimate liberator. Humanity has at times lived with that story and limited that story. How did you get a sense of that? How did you balance scale?

Levins Morales: There’s a question I can’t answer, except to say that we live in all of these scales simultaneously, right? I think partly it has to do with curiosity being something that was encouraged in my family and nurtured. Thinking about the stars, thinking about the dirt that I played in, thinking about the parasites I got into me from the dirt that I played in. Thinking about all these things, and then over time, seeing the connections among all of them. I didn’t grow up writing poetry or anything. But I did remember in my brief stint in high school, there was a class assignment where we had to write a short poem. And what I wrote, what I chose, was something about a little bead of glass being formed on a beach of sand under the pressures of heat. This tiny little fragment reflects the stars at night. That juxtaposition between entirely different scales coexisting has always fascinated me.

Workday: You write about your sister a lot too. I feel like that sibling relationship is important. There’s a kind of solidarity there, within the scale of a family household, having someone alongside you helps.

Levins Morales: When you’re in alignment!

Workday: And of course there are times when you’re not in alignment, and that’s where I’ve learned a lot about how to repair things. We’re almost forced to learn how to do that, because we’re in this environment together.

Levins Morales: In the organizing world, I have often described family as a gift to organizers, because you often end up in relationship with people who you disagree with on everything and you still either love them or have to at least tolerate them and remain in relationship. You can’t throw them away.

Workday: There’s a lot of labor history in here that I learned about, but also, critiques of the labor movement and unions. There is a lot of restoring, or re-storying, that needs to happen. What are your thoughts on how the labor movement can be better at building solidarity with the land? How do we re-story those relationships?

Levins Morales: It comes with that same formula that I keep drumming like a rhythm throughout this book. You ask a bigger question. If your mission is defined narrowly, then you’re in competition with everybody. If it’s performed broadly, you’re in solidarity. The classic, engineered conflict between environment and jobs, right? That’s totally manufactured. Why do we want jobs? So that our children can be fed, so that we can have a better life? Okay well, what else contributes to a better life? How do we bring those things into alignment, rather than choosing one over another and paying a heavy price for it later?

I want to give people permission to think unthinkable thoughts. To go there and try out different ways of questioning the orthodoxies we’ve inherited. Sometimes after that questioning, we realize how wise they were, sometimes not so much, or that there’s a kernel that’s worth salvaging and other things that need changing.

Workday: There’s a part where you write about democracy and how exploitation happens hand in hand with “elite democracy.” There’s a lot of frustration in the movement history you write about regarding democracy. Why are we propping up a system that still doesn’t serve the needs or desires of the majority of the people or the planet?

Levins Morales: It’s about diagnosis, right? If you misdiagnose, you’re going to come up with a treatment plan that doesn’t get you where we’re going, and the outcomes won’t be good. So if you’re diagnosing that these things need to be tweaked so the system will work, then you’ll forever be tweaking the system. I say in the book, the way the system actually works is, after enough tweaks, it triggers a reset. Which is something that is a new idea to most organizers. They think that it’s this back-and-forth pushing and whoever pushes hardest. I think it has to do with clarity, one of the three essential elements of organizing. You have to have that clarity in order for your interventions to go to the root of the problem. Because if you don’t go to the root of the problem, of course you’re going to still keep experiencing the same struggles. Well, duh, the same empire is in place. The same substructures are in place. It’s interesting to live in a time where it’s actually possible to talk at least somewhat about these things. For much of my organizing life, you couldn’t hold a rational conversation that mentioned the word “capitalism.” And now even the mainstream talks about it because it functions so badly. They don’t talk about it being inherently problematic, but they do talk about it being in crisis.

It’s partly about communicating on multiple frequencies. At this moment, I think something as broad as “No Kings” is a good thing to bring the maximum number of people into the street. But on top of the Palestine movement, on top of the Black Lives movement, the seeds of deeper analysis are there. A lot of people are at, “No, let’s just return to a rational, well administered Empire.” But a lot aren’t. People with a deeper analysis have to keep drumming that deeper analysis. Doing that while simultaneously blocking a fascist coup is important because fascism is nothing to trifle with, and people just think “oh, well, we’ve lived through that before. We’ve lived through police repression.” No, it’s not like what people have lived through. When you have a real fascist state, you have very little room to breathe. And if you read the lives of people who have lived clandestinely in struggle, you know, you can spend three weeks setting up a clandestine meeting with somebody in a public place. Be sitting there for the rendezvous and just get a creepy feeling at the back of your neck and jump on the next bus and go away. All that effort is lost because there might have been somebody surveilling you.

Hundreds of thousands of people have participated in “No Kings” and “Hands Off” rallies across the U.S. this year to protest the Trump administration’s policies targeting of working class communities. Photo by Amie Stager.

Workday: There are so many nuggets of wisdom I’m gonna take with me. There’s a part where you unpack the saying about the definition of insanity, doing things over and over again and expecting a different result, and also your mother’s saying about preaching to the choir, “That’s how you get them to sing!”

Levins Morales: Notice that both of those examples that you gave are flipping something that’s very well known and widely accepted frameworks.

People are hungry for truth telling, but truth telling has a smaller audience to begin with, because it’s not within people’s realm of comfort or familiarity. That’s how the Right came to dominate, by continuously telling their story even when it was a story that most people didn’t take seriously. Instead of watering it down to be more widely accepted, they just kept up the drum beat.

Workday: What kinds of art should working people or unions be looking into and making?

Levins Morales: The answer is, whatever’s needed and whatever’s useful. Possibly as far back as the 1980s I’ve been doing workshops on creative organizing at Labor Notes. For a long time, we had a parallel sub conference called the conference on creative organizing, which was trying to bring organizers, not just artists, in to use that kind of creativity. What about working with union members to create art about their workplace? Tapping into creativity where it is embedded in the workplace, and not necessarily getting these outside artists to do big, showy stuff.

Ricardo Levins Morales, “ABCs of Organizing,” Northland Poster Collective Archive, accessed August 21, 2025, https://omeka.northlandpostercollectivearchive.org/items/show/147.

Workday: You write about people of different streams and lineages of thought, the history of people who have asked these questions before and how the questions and answers have evolved. A lot of the questions we’re asking now have been asked before, right?

Levins Morales: They might have found answers that had a shelf-life. That’s also an ecological sensibility. The plants that grow in a newly disturbed area create the conditions for the next wave of plants. Weeds that grow by a roadside that’s been disturbed or after a fire need sunlight, which means that their own seeds can’t grow in their shadow. They have to be blown away by the spores and then the next succession. The answers that were found by one generation were the right answers, as right as they could be at that time, but they’ve created conditions that have changed. The answers need to be different now.

Amie Stager is the Associate Editor for Workday Magazine.

Workday Magazine holds the powerful to account while bringing the perspectives of everyday workers, and the organizations that defend their rights, to focus. We emphasize long-form investigative journalism to unearth the concealed and buried. Our publication is based in Minnesota and covers the greater Midwest, along with international issues that affect workers, like climate change and U.S. militarism.

Spread the word