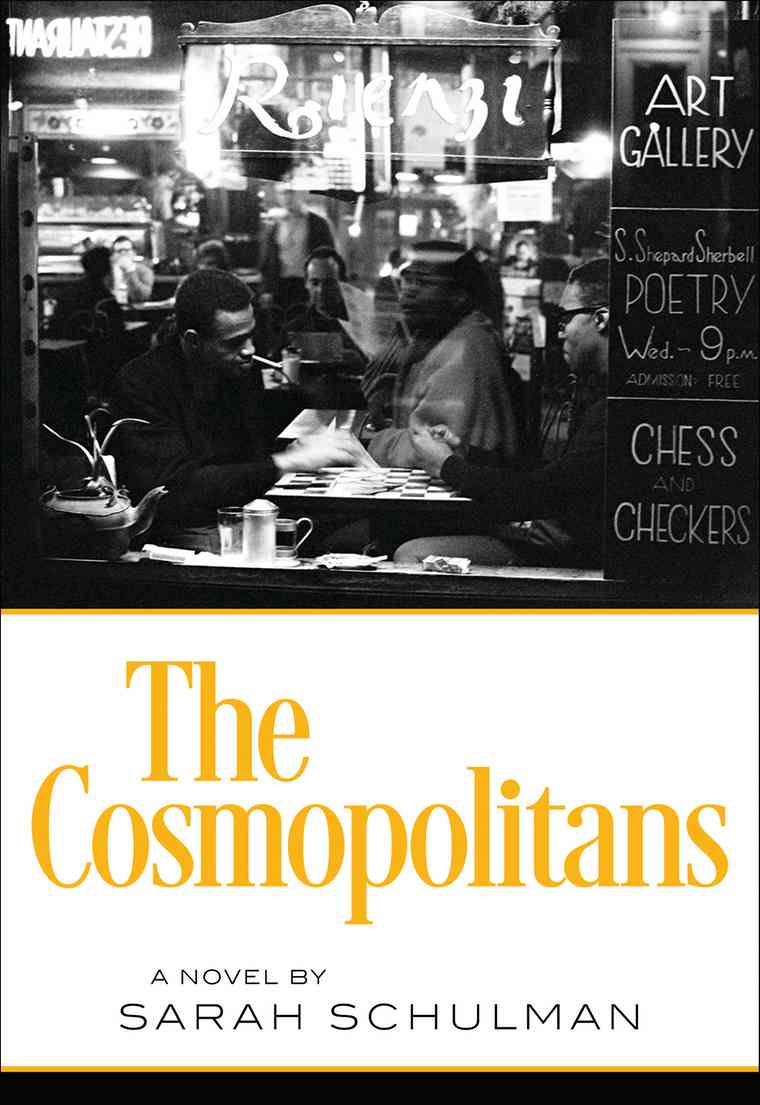

By Sarah Schulman

The Feminist Press at CUNY College, 390 pages

Paperback: $15.95 (order from the Feminist Press for $12.76)

March 15, 2016

ISBN-13: 978-1558619043

Just as the writer Sarah Schulman and I were finishing up our interview, on a rainy March morning in Manhattan's East Village, I asked her: what did she think of the state of lesbian content in the arts today?

"Horrible," she said. The problem with contemporary American representation of lesbians, Schulman continued, lay in the nation's obsession with the family. "There are no representations of lesbians right now that have broken into the popular culture [not about] a person in a family context." The normalizing structure of the family allows the non-normative family member to be seen by broader society: until that structure can be dispensed with and replaced by the honest perception of lesbians as full human beings, Schulman thinks there will be no improvement.

Schulman's career has been devoted to social change. In recent years, she has committed to the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel, and was just last week accused by the the Zionist Organization of America of antisemitism for it. Schulman uses her writing to shed light where there has been darkness - where HIV and Aids should be in the record of American history, and where LGBT lives, especially lesbian lives, should be in the narrative arts. We were meeting to talk about her newest novel, The Cosmopolitans, and its place in a long, illustrious, and underrated career.

The Cosmopolitans is about a white spinster named Bette and her best friend and neighbor Earl, who is a black, gay actor. The book is indebted to Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin and Balzac's Cousin Bette, something Schulman openly acknowledges in an afterword.

"It's a weird perspective for normative people," Schulman said, meaning, I think, that the books' main characters were not people with whom readers of commercial fiction were ready to identify. "There's no protagonist," and the world of the book isn't very big and social, or family-oriented. The book follows the fates of a "white spinster, who is an icon of literature, but is not the person that any reader wants to identify with" and a "black, gay man in the 1950s in New York", a subject Schulman claims "has only been done by two people, James Baldwin and Samuel Delany". It's a novel about friendship.

Schulman can claim a long history of writing characters whose backgrounds are not from her own experience. Her first novel, she pointed out to me, contained an Asian lesbian character, and she has been writing black, male characters since 1986's Girls, Visions and Everything. She does so by listening first, she says, then by hearing - not the same thing, of course, and not always perfectly done.

Jacqueline Woodson rebuked her for making a black character anxious about her newly discovered white ancestor in her 1998 novel Shimmer. "Jackie pointed out to me that that's a white anxiety, it's not a black anxiety," Schulman said, which was "kind of mortifying to recognize" but crucially important: "That was 18 years ago, so I've had a lot more time to do the work since then."

The Cosmopolitans, Schulman told me, is about two things: being blamed for something you haven't caused, and white supremacy. Bette feels a desperate need to correct and deflect undeserved blame laid at her feet by Earl, but she does so with the tools of racism. Every white person, Schulman explained, has white supremacy at their fingertips, whether they know it or not.

"If representations of white people were accurate and honest," Schulman said, this would be our assumption of every white character in fiction. Instead, "we have almost no white characters for whom this is acknowledged". Bette isn't bad, says Schulman. "She's not a villain while the rest of us are fine. She's just fully candid, and most white representation is propagandist."

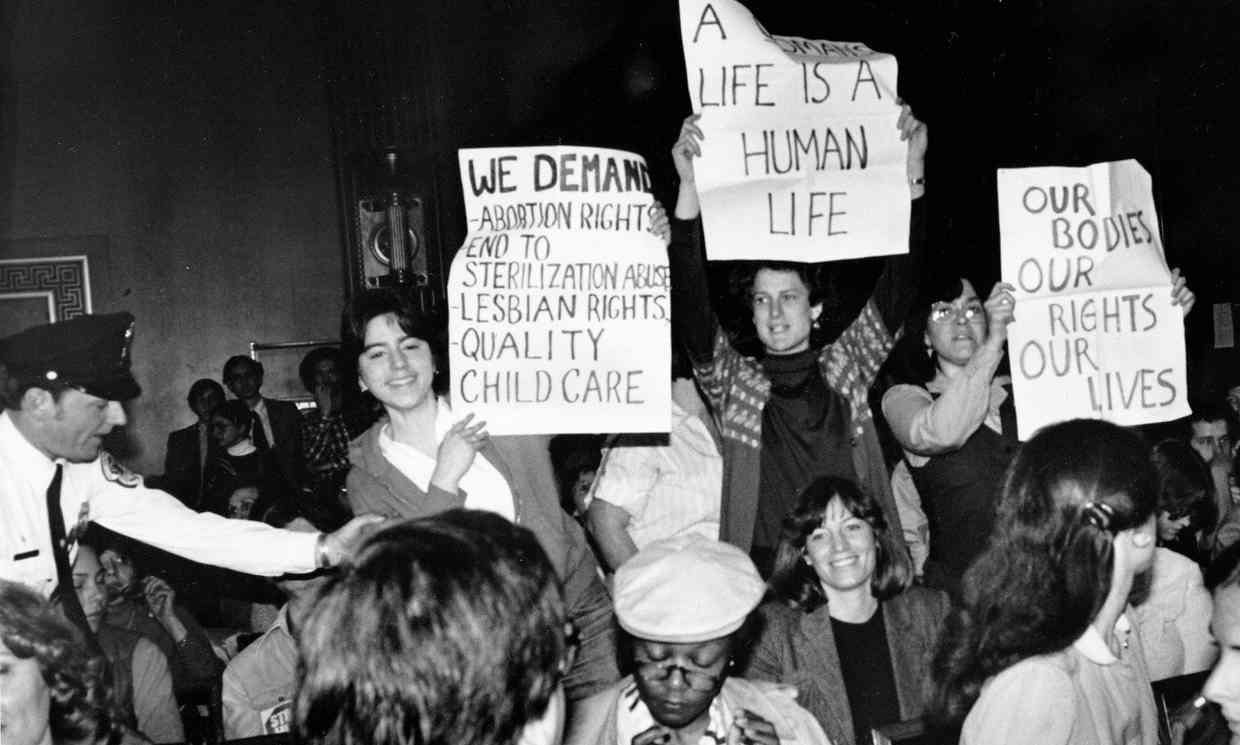

Schulman has another nonfiction book coming this fall, Conflict is not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility and the Duty of Repair, about the culture's dominant tendency to overstate conflict as harm: white cops interpreting conflict with black men as direct threats to their safety, for example. And in her life generally, she has directed equal energy to political activism and to literary expression. Her activist career reaches back to her childhood protesting the war in Vietnam with her mother. She and other feminist organizers disrupted a 1982 anti-abortion session in Congress.

Schulman at a pro-choice protest in the 1980s.

Photograph: Feminist Press

Schulman was also a longstanding member of Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power), a group founded in New York in 1987 and dedicated to direct action advocating for people with Aids. More recently, Schulman founded the Act Up Oral History Project with Jim Hubbard to record the organization's legacy "while also revealing the complexity and diversity of the organization and the immense ingenuity and talent that made it possible for Act Up to change the face of Aids in America".

In her recent, affecting book Gentrification of the Mind, Schulman gives a heart-shattering account of the lives and deaths of the awful number of her friends who died in the "plague years" of Aids:

The years from 1981 to 1996, when there was a mass death experience of young people. Where folks my age watched in horror as our friends, their lovers, cultural heroes, influences, buddies, the people who witnessed our lives as we witnessed theirs, as these folks sickened and died consistently for fifteen years. Have you heard about it?

Schulman goes on to explain how the gentrification of the Lower East Side coincided with this mass death, properties flipping to market rate as their tenants died and their partners could not inherit them, all overseen by a totally indifferent government. "Strangely, this relationship between huge death rates in an epidemic caused by governmental and familial neglect, and the material process of gentrification is rarely recognized. Instead gentrification is blamed on gay people and artists who survived, not on those who caused their mass deaths."

Schulman's point about our quickness to blame gay whites for a gentrification process really engineered by policy is well taken. The text is important in my own little queer community, such as it is, but everybody has their objections. The book raises more questions than it answers. Why bother to exculpate a generation of whites, for example, when there's so much to be done now, so much responsibility left to be taken?

I was about to explain some of these objections to Schulman in our corner of the coffee shop, but she interrupted: "You know I'm an artist, right? I'm not an academic, so when I write something, I'm not claiming that it's right. I don't have footnotes. I can't prove anything that I say. I don't do the one long, slow idea. I do a hundred ideas. There are a hundred ideas about this subject and I want the reader to go, `Yes! No.' I want that interactive relationship with the reader."

It's a convenient argument, but also a convincing one. Certainly, the debates I've had with friends about gentrification have been consciousness-raising, and this, Schulman says, is what she's trying to do in both her fiction and nonfiction. "Maybe that's the link," she conceded. "Maybe I write nonfiction as an artist." Her writing constantly intervenes, but always seeks to initiate new discussions rather than joining old ones. Schulman's is a literary-activist practice of remarkable elasticity: she continually demands a new world through creative engagement, and fills in the gaps as she goes.

[Josephine Livingstone is a doctoral candidate and teacher at New York University.]

Spread the word