FEMA gets no respect.

Consider: The two men who are supposed to be helping run the federal government’s disaster response agency had a pretty quiet late August. Even as a once-in-a-thousand-year storm barreled into Houston, these two veterans of disaster response—Daniel A. Craig and Daniel J. Kaniewski—found themselves sitting on their hands.

Both had been nominated as deputy administrators in July, but Congress went on its long August recess without taking action on either selection—despite the fact that both are eminently qualified for the jobs.

Leaving the roles open as the annual Atlantic hurricane season arrived was the clearest recent sign that FEMA—an agency whose success or failure translates directly into human suffering avoided or exacerbated—barely registers in Washington.

In fact, FEMA has always been an odd beast inside the government—an agency that has existed far from the spotlight except for the occasional high-stakes appearance during moments of critical need. It can disappear from the headlines for years in between a large hurricane or series of tornadoes.

But FEMA’s under-the-radar nature was originally a feature, not a bug. During the past seven decades, the agency has evolved from a top-secret series of bunkers designed to protect US officials in case of a nuclear attack to a sprawling bureaucratic agency tasked with mobilizing help in the midst of disaster.

The transition has not been smooth, to say the least. And to this day, the agency’s weird history can be glimpsed in its strange mix of responsibilities, limitations, and quirks. And then there’s this fun fact: Along the way, FEMA’s forefathers created a legacy that is too often forgotten. Inside those bunkers during the 1970s, the nation’s emergency managers invented the first online chat program—the forerunner to Slack, Facebook Messenger, and AIM, which have together transformed modern life.

FEMA didn’t start off as FEMA—in fact, it has been reshuffled and reorganized more than perhaps any other key agency in recent US history. Harry Truman started FEMA’s forerunner, the Federal Civil Defense Administration, in 1950. One newspaper columnist at the time had a succinct summation of the new agency’s shortcomings: “The Federal Civil Defense Administration has had no authority to do anything specific, or to make anyone else do it.” Unfortunately it’s a criticism that would continue to ring true, straight through natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

Bureaucratic indifference has marked nearly every aspect of the nation’s homeland security operations, a point best indicated by the FCDA’s evolution: Over the following decades, it migrated regularly between different departments and underwent nearly a dozen name changes and agency affiliations before eventually becoming the Federal Emergency Management Agency in the 1970s. After the 9/11 attacks there was yet another organizational reshuffling, and the agency finally ended up part of the Department of Homeland Security in 2003.

Most of these various predecessors to FEMA weren’t all that concerned with civilian natural disasters. They were primarily focused on responding to nuclear war; the evolution to being the first call after a hurricane, flood, or tornado came about in part because it turned out America doesn’t have all that many nuclear wars—and the equipment and supply stockpiles and disaster-response experts at FEMA’s predecessors were useful for something other than the apocalypse.

FEMA was the result of Jimmy Carter’s efforts to restore some primacy to civil defense planning, bringing it back into the spotlight after years of diminishing budgets. The administration threw its weight behind a congressional effort to reestablish what was then known as the Office of Emergency Preparedness under a new name, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, uniting the nation’s disaster response with its planning for “continuity of government,” the secret programs that were supposed to snap into place in the event of nuclear war.

Created in April 1979, FEMA brought together more than 100 programs from across the government; publicly, the agency would be known for coordinating the government’s response to natural disasters like floods, hurricanes, and tornadoes. But few in the public understood that much of FEMA’s resources went instead to its primary mission—coordinating the nation’s post-apocalypse efforts—and that the majority of its funding and a third of its workforce was actually hidden in the nation’s classified black budget. The agency’s real focus and its real budget was known to only 20 members of Congress.

Indeed, FEMA was hobbled from the start, limited by weak central leadership, full of political patrons, and pulled in multiple directions by its disparate priorities—some public, some secret. As one Reagan-era assessment of the agency concluded, “FEMA may well be suffering from a case of too many missions for too few staff and resources.… FEMA itself might be a mission impossible.”

Today, conspiracy theorists fear that FEMA is setting up concentration camps to house political dissidents (Google “FEMA camps” if you want to lose an hour or two in a rabbit hole). The truth is a bit stranger: FEMA, as it turns out, doesn’t construct camps for political dissidents—but it started by taking one over.

The cornerstone of FEMA’s secret world is a bunker in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains that has served as the civilian government’s primary emergency hideaway since the 1950s. Mount Weather’s name comes from its use as a research station and observatory for the Weather Bureau dating back to the 1890s. At the turn of the 20th century, the observatory was known for its pioneering science, using elaborate balloons and box kites to study the atmosphere at a time when meteorology was in its infancy. The nascent Weather Bureau, the forerunner of the National Weather Service, picked the isolated site because it was far away from that era’s cutting-edge technology—electrical trolley lines, whose troublesome electric currents could throw off magnetic observations. “We are looking to the future needs of a rapidly developing and intensely interesting branch of science,” the observatory director explained, “and are trying to build the very best observatory possible.” Using motor-operated rotating steel drums lined with as much as 40,000 feet of piano wire, Mount Weather’s kite team broke its own world altitude record in 1910, flying a kite 23,826 feet into the air and recording the lowest temperature ever (29 degrees Fahrenheit below zero) using a kite-launched instrument.

As meteorology advanced and better technologies arrived, the Weather Bureau handed off the majority of the 100-acre facility to the Army for use as a World War I–era artillery range. The government then spent the better part of the 1920s trying without success to get rid of the property. Later still, beginning in 1936, Mount Weather became a Bureau of Mines facility where the agency tested various boring methods. The rock on the mountain was exceptionally dense, and the bureau began building a narrow but lengthy tunnel into the mountain for experiments on blasting and drilling methods.

During World War II, the government housed as many as 100 conscientious objectors there, pressing them into service as weather researchers to help develop better forecasts for the Northern Hemisphere. After the war, the facility went back to the Bureau of Mines, which redoubled its efforts at developing new boring techniques. In a lengthy 1953 report on the “widely acclaimed” problems solved by the mountain’s engineers, the Interior Department bragged, “From Mount Weather in the last few years has come a mass of technical data on drilling, steels to use in drills and rods, diamond drilling, and related subjects.” Its work on diamond drill bits was considered, well, groundbreaking.

That publication was one of the last public mentions of the site for decades. Even as the Interior report went to press, the government began to slowly expunge the existence of Mount Weather from official mention. The Soviet Union now had atomic weapons; the Cold War was on, and preparations for an all-out nuclear exchange had to be made. Given its distance from Washington, its exceptionally hard rock, the preexisting tunnel, and its pre-located boring machines, Mount Weather was a perfect place to outfit an executive-branch bunker. If the worst happened, the American government could continue to function underground.

Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center in Virginia served as a secret bunker that would house senior US officials in case of a nuclear war. Karen Nutini/FEMA

Beginning in 1954, just a year after the Pentagon’s backup bunker at Raven Rock became operational in Pennsylvania, the Army Corps of Engineers began a four-year expansion project that would transform Mount Weather into the nation’s largest underground complex. “Operation High Point” enlarged the original tunnels, excavating hundreds of thousands of tons of greenstone and hollowing out a cavern large enough for a medium-sized city under the mountain. More than 21,000 iron bolts reinforced the roof. While the facility wasn’t fully completed until 1958, it began serving as the executive branch’s main relocation site almost immediately, hosting Eisenhower’s evacuation drill Operation Alert in 1954. According to a perhaps apocryphal story, the first director of the Mount Weather bunker was given a simple commission directly from President Eisenhower: “I expect your people to save our government.”

By the Kennedy years, Mount Weather included all the amenities and life-support systems of a top-of-the-line bunker: Helicopter landing pads and a sewage treatment plant were atop the mountain, but underneath was where the real facility existed, with underground reservoirs for both drinking water and cooling needs, diesel generators, a hospital, radio and television broadcast facilities, cafeterias, its own fire department and police force. Some 800 blue mesh hammocks sat ready for evacuated personnel, who would sleep in shifts throughout the day. Plastic flowers dotted the tables in the cafeteria.

It was just one of dozens of bunkers and relocation facilities that FEMA’s predecessor agencies built around the country, including what it called Federal Regional Center bunkers in places like Denton, Texas; Maynard, Massachusetts; Thomasville, Georgia; Bothell, Washington; and Denver, Colorado. The Denton center, the first to open in 1964—and still in use today—was a 50,000-square-foot, two-level bunker that could have supported several hundred officials for 30 days. It had its own drinking well, laundry facilities, diesel generators, and 13-ton blast doors. The facility kitchen could have served 1,500 meals a day and its walk-in freezers could double as a morgue. The centers also included duplicates of vital records, to help affected agencies maintain continuity of operations. Any of the facilities could be used by the president or other high-ranking government leaders if they happened to be caught nearby during an attack, and they had broadcast booths ready to connect to the nation’s Emergency Broadcast System.

This elaborate network of national bunkers—and the unique responsibilities they had in hosting US officials after a nuclear attack—made FEMA’s predecessors and the national continuity-of-government program leaders in the developing field of computers and technology. By the early 1970s, Mount Weather and what was then known as the Office of Emergency Preparedness had amassed some of the most sophisticated and cutting-edge computers in the world to help it respond to the complex scenarios of an unfolding attack.

A large specially built bubble-shaped pod inside Mount Weather’s East Tunnel contained several advanced computers, which were disconnected from the network at 9 pm each night so that teams could conduct classified research and computations until 8:30 am the next day. Inside the pod, the room-sized UNIVAC 1108 supercomputer, which retailed for about $1.6 million, represented the cutting-edge technology of multiprocessors, allowing the computer to do multiple functions at once. “I’m at a loss to describe its maximum capacity,” a UNIVAC executive said at the time, awed by the processing power installed at Mount Weather.

Those computers deep inside Mount Weather helped spawn one of modern’s life most transformative technologies.

Murray Turoff was a young PhD graduate from UC Berkeley when he crossed paths, during a NATO conference in the 1960s in Amsterdam, with Norman Dalkey, one of the lead developers on a RAND project known as Project Delphi. Its purpose: to help the government harness group decisionmaking. One evening after the conference sessions were over, the two computer scientists had intended to tour Amsterdam’s famed red-light district, but ended up talking late into the night about the work Turoff was doing on war game simulations. Both men were keenly interested in human collaboration, and Turoff was soon sucked deeper into the government’s secret Doomsday planning operation, joining the Office of Emergency Preparedness to work on collaboration and information sharing. Earlier crisis networks had been frustrating failures; a very primitive one created by the military and US government during the Berlin airlift in the 1940s had been quickly overloaded by the volume of messaging. But by the Nixon years computers had advanced enough to make such communication systems practical.

At OEP, Turoff worked with Dalkey’s Project Delphi team to speed up the expert analysis and harness the knowledge of hundreds of informal and formal presidential advisers on emergency situations. His first crisis wasn’t nuclear; it was Nixon’s August 1971 wage-price freeze, which attempted to pull the nation’s economy out of an inflationary spiral. Under orders to deliver a monitoring network in just a week, Turoff developed a system in just four days that came to be known as the Emergency Management Information System and Reference Index—with the inevitable acronym EMISARI, which allowed 10 regional offices to link together in a real-time online chat, known as the “Party Line.”

While the system was meant to work in parallel with the normal OEP conference calls and faxes, Turoff and his team found that EMISARI’s efficiencies quickly outpaced everything else and that the organization’s conversations migrated online quickly. Entries were limited to just 10 lines, to prevent, Turoff recalls, people writing “typical government memos” inside the system.

In the first 10 weeks of the wage-price crisis, the 80 officials on the system turned to EMISARI 900 times to enter data; they exchanged nearly 3,000 messages—a phenomenal rate for the early days of computing. EMISARI proved to be the forerunner of later electronic chat functions like AOL Instant Messenger and text messaging.

The system also included seven master text files that laid out general policies and guidance, a comprehensive list of the actions being taken by headquarters and the various regional offices as well as abstracts of news stories and press releases—all of which could be updated in near real-time and disseminated nationally in an instant.

After its first successful test during the wage freeze, EMISARI and its successor systems became an integral part of OEP’s response to other economic disruptions in the 1970s, like the gasoline shortage and trucker strikes in 1974 and 1979. For an agency tasked with responding to a crisis that could unfold across the country simultaneously, EMISARI represented a huge breakthrough—and one that the regional directors quickly realized would be critical in continuity operations. “A conferencing capability would be highly useful under [a nuclear attack scenario], particularly during the transattack and immediate post-attack period when everybody would have to be holed up and face-to-face conferences would be impossible,” said EMISARI’s project manager, Richard Wilcox.

By 1974, a system for quickly gathering and storing important data was also emerging. As Wilcox explained: “Access to the national resource database and associated nuclear damage estimation models could support analysts attempting to figure out what could be done with what was left after a nuclear attack.”

In fact, EMISARI was an integral part of the growing number of computerized resources that the Office of Emergency Preparedness was building into its facilities like Mount Weather to serve as the backbone of the nation’s crisis response systems. Two other major components of the OEP’s “Civil Crisis Management” system were its “Contingency Impact Analysis System” (CIAS) and its “Resource Interruption Monitoring System” (RIMS), which were meant to help officials respond to critical shortages and to shuffle much-needed resources around the country to respond to unfolding situations.

The systems had preprogrammed crisis scenarios, each of which had clearly delineated steps and notified each stakeholder in turn as their role became critical; for the time, it was very advanced networking technology, containing early versions of what later generations would recognize as email, bulletin boards, and chat functionality. “The computer as a device to allow a human group to exhibit collective intelligence is a rather new concept,” Turoff said presciently in 1976. “Over the next decades, attempts to design computerized conference structures that allow a group to treat a particular complex problem with a single collective brain may well promise more benefit for mankind than all the artificial intelligence work to date.”

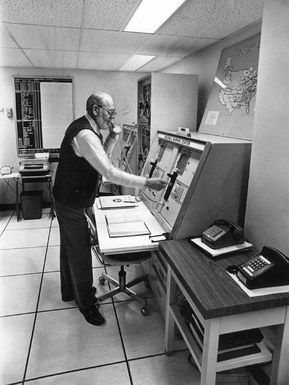

FEMA personnel at the Regional Warning Center were tasked with responding to nuclear emergencies. Dave Buresh/Denver Post/Getty Images

As tech historian Howard Rheingold has written, EMISARI, RIMS, ARPANet, and similar efforts were a major leap forward in information processing. By grouping and processing messages around given subject matter, the scientists and engineers “were all discovering something that had been unknown in previous communication media—the content of the message is capable of also being an address. Far from being a tool of dehumanization, the computer conferencing system could boost everybody’s ability to contact a community of common interest.”

The advanced computers also greatly improved the continuity of government programs’ war gaming scenarios, allowing much more sophisticated modeling of how the nation would respond in the hours following a nuclear attack. “Once we’re briefed, we’re given two hours to develop a strategy or plan of action,” explained one official who played a Cabinet secretary during an exercise at Mount Weather. “The decision of each department is fed into a computer and the display consoles tell us whether our choices had improved the situation or created new problems.”

OEP and its successor, FEMA, carefully collected data, including latitude and longitude, on more than more 2 million structures across the country that it planned to monitor in the event of a nuclear attack—everything from 10,873 grain silos to 8,184 hospitals, not to mention the 316 mines and caves it had scouted over the preceding decades that could be used to house industrial manufacturing and processes in the wake of a nuclear war. Nearly every conceivable statistic had been carefully calculated and stored for later retrieval; a 6,000-megaton attack on the US, for instance, would destroy much more of the production of alcohol and tobacco products than the population itself, meaning that after a war, liquor and cigarettes would require “drastic rationing.” By completing the calculations in advance, government planners would be able to begin to calculate survival rates even when the attack was still underway, although it was difficult to know how accurate the results would turn out to be. “We’ve never had a war to calibrate the programs,” one official explained in the 1980s.

If there were a nuclear war, FEMA would be the first to know. And it had a chillingly rational plan for responding. Through the Cold War, its watch center in Olney, Maryland, ran daily drills of its radio and telephone systems at 1:15 pm and at 1:30 pm. Had the military detected the start of a nuclear war, one of the two FEMA officers at the agency’s National Warning Center inside the NORAD bunker at Cheyenne Mountain, Colorado, would have activated a special dedicated AT&T party line and announced the threat: “Alternate National Warning Center, I have an emergency message.”

“Authenticate,” the watch officer at FEMA’s alternate facility in Olney would have challenged. The authentication codewords for the system were distributed in a red envelope every three months to all the users of the emergency broadcast system; codewords were generally two- or three-syllable words, two for every day of the year—one for the activation of a warning, one for the termination of a warning.

Then, following the NORAD watch officer providing the correct authentication code, the Olney’s watch officer would activate the national alert—bells would sound at Mount Weather and all 10 regional FEMA headquarters, as well as at 400 other federal facilities and more than 2,000 local and state “warning points,” such as emergency 911 dispatch centers. Each warning point would hear the same message: “Attention all stations. This is the National Warning Center. Emergency. This is an Attack Warning. Repeat. This is an Attack Warning.”

The FEMA watch officers would also activate a separate system to announce the attack to the national media, radio, and television broadcast networks—breaking into national programming with the alert. Similar alerts would go out from the FAA to all airborne pilots, from NOAA on the national weather radio network, and from the Coast Guard to mariners afloat. Some of the nation’s warning systems were more unconventional: A plexiglass-shielded Button No. 13 in the DC mayor’s emergency command center, at 300 Indiana Avenue NW, just a few blocks from the US Capitol, would activate “Emerzak,” seizing control of the city’s entire “Muzak” network, replacing the piped-in bossa nova of the city’s elevators, lobbies, medical offices, and department stores with emergency instructions.

Yet even after all that effort, it wasn’t clear how much difference the warnings would make to most of the public. “The people who hear them will run into buildings and be turned to sand in a few seconds anyway,” explained Lieutenant Robert Hogan, New York’s deputy head of civil defense, in 1979.

But the warning would have made a big difference to one of FEMA’s other secret tasks: Figuring out the highest federal official still alive after an attack and designating that person President of the United States.

Beginning during the Cold War and continuing up to the present day, FEMA’s Central Locater System tracks the whereabouts of all the officials who are in the presidential line of succession, 24 hours a day, ensuring the government is ready to whisk them away from their regular lives at a moment’s notice. They work closely with a special team of Air Force helicopter pilots who practice in the skies over Washington daily, ready to drop onto helipads, well-groomed lawns, the National Mall, and even sports fields if necessary, to ensure the survival of those chosen few.

In April 1980 President Carter’s White House Military Office instituted new procedures with FEMA to monitor the attendance of all presidential successors “at major, publicly announced functions outside the White House complex.” While such gatherings of the US leadership had been commonplace in the past—at inaugurations, States of the Union, state funerals, and the like—the rising tensions of the Cold War made continuity-of-government planners questions their wisdom. “The situation provides an inviting target to enemy attack or terrorist activity, and represents an unnecessary risk to national leadership,” the White House Military Office wrote, outlining the new procedures.

When such gatherings seemed imminent, FEMA was to notify the White House and the assistant to the president for national security affairs would recommend to the president which successor should skip the event and serve as the designated survivor. The Central Locator System tracked the whereabouts of the successors daily, and once a month, after the fact, audited a single day to determine whether it had correctly known where each Cabinet member was. The new White House and FEMA procedures got their first test at Reagan’s inaugural—and it’s a protocol that continues to the present day.

While government officials would have been rushed by helicopter to Mount Weather, FEMA also devoted extensive planning in the 1980s to scout where the civilian population would live after a nuclear attack, embarking on a top-secret effort with the FBI known as Project 908 (or “Nine Naught Eight,” as it was called) to map the nation’s commercial buildings for possible refugee resettlement—all part of a larger 1980s program, known as Crisis Relocation Planning, that calculated how to evacuate the nation’s major cities.

Project 908 saw FBI agents, working effectively undercover for FEMA, detailing large warehouses, automobile facilities, Masonic temples, Elks lodges, casinos, camp sites, Coca-Cola bottling plants, Indian bingo halls, country inns, furniture stores, and other potential relocation facilities. In Arkansas, agents lined up a meeting with Walmart executives to discuss using the company’s huge stores for Project 908, explaining as a cover that they wanted to learn crisis management techniques from companies that had large centralized leadership. Denver agents dismissed a closed Coors brewing plant in Colorado because the caretaker was “loose-mouthed.” Meanwhile, in Redding, California, 160 miles north of the state capital, FBI agents approached the owner of Viking Skate Country (“Redding’s fun center for kids!”), known to the government as “Sacramento Site #34,” and outlined their proposal. The owner responded enthusiastically, telling agents he was a “fiercely loyal American” and would “cooperate fully.”

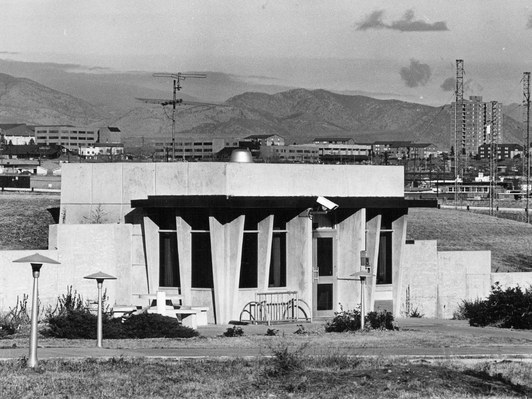

Underground bunker at Denver Federal Center. Dave Buresh/Denver Post/Getty Images

FBI agents presented cooperating business owners with secret agreements to “rent” their facilities for nuclear war. Lengthy addendums to the contracts outlined required utility and infrastructure upgrades needed to support crisis operations, the costs of which were fully paid by the government, as were separate telephone lines installed at each facility. The government also paid a token annual fee on the order of $1,000 or $2,500 to ease cooperation. During an emergency, the FBI would also pay a daily fee for each day it occupied the facility. Nowhere was any government agency other than the FBI mentioned—FEMA kept its fingerprints far from the program.

Under the Crisis Relocation Plan, nearly 150 million Americans—out of the country’s then total population of 225 million—would be evacuated out of 400 “high-risk” cities into smaller surrounding towns and these preselected buildings; under FEMA’s estimates, some 65 percent of that population could be evacuated in as little as one day and fully 95 percent could be evacuated in three days. Such strategic warning, FEMA estimated, would be achievable under most circumstances, since it was “more likely that [a nuclear attack] would follow a period of intense international tension.”

Under FEMA’s plans, the agency had a multistage effort for informing civilians about how best to evacuate. First would come “Protection in the Nuclear Age,” a 25-minute bilingual film produced in 1978 that would air across the country, outlining the threat—and the hope. Copies of the film were distributed in advance to civil defense officials and some television stations, and 15 prewritten newspaper articles distributed by FEMA covered much of the same ground.

The low-tech film featured only illustrations and animations of stick figures—no live action—because by the 1970s civil defense planners had grown tired of retaping propaganda films every time fashion or car styles changed. As one FEMA official explained, “Stick figures don’t get obsolete.” The film tried to put an optimistic spin on nuclear war, providing hope and underscoring that survival was not only possible but—with planning—probable. “Defense Department studies show that even under the heaviest possible attack, less than 5 percent of our entire land mass would be affected by blast and heat from nuclear weapons,” the film’s narrator explained, as red flashes exploded across the United States.

As the film closed the narrator warned, “The greatest danger is hopelessness, the fear that nuclear attack would mean the end of our world. So why not just give up, lie down, and die? That idea could bring senseless and useless death to many, for protection is possible. And your own chances of survival will be much greater if you remember these facts about Protection in the Nuclear Age.”

Then would come detailed evacuation instructions: FEMA would distribute millions of preprinted brochures, perhaps going door to door or perhaps by distributing it with local newspapers. They also took out ads in local telephone books. “As the crisis intensifies and evacuation appears imminent, if you have a vacation cabin or relatives or friends outside the Risk Area, but within a safe distance, go there as soon as possible,” the brochures explained.

Together, FEMA estimated the multimedia campaign would boost survival rates by 8 to 12 percent. All told, FEMA officials during the Reagan years were surprisingly optimistic about nuclear Armageddon. “You know, it’s an enormous gigantic explosion,” FEMA’s head of civil defense, William Chipman, said in one interview. “But it’s still an explosion and just as if a shell went off down the road, you’d rather be lying down than sitting up, and you’d rather be in a foxhole than lying down. It’s the same thing.”

Nationally, FEMA estimated that the efforts, given three or four days warning, would save about 80 to 85 percent of the US population—roughly 15 to 20 percent of the population, planners estimated, would die simply because they refused to evacuate or because they couldn’t evacuate, “the sick, the disabled, and handicapped, people with mental problems, alcoholics, drug addicts, and some of the elderly lonely.”

Even the evacuation of major cities like New York City were carefully planned. “Nobody’s suggesting you could move New York City in 15 minutes. That’s stupid,” Reagan’s FEMA chief, Louis Giuffrida, explained. “But we could do New York if we had a plan in place; we could do New York in five days, a week.”

However impractical in reality, there was no faulting the level of detail of the 152-page plan for evacuating New York, which included both a primary plan and 11 alternatives. Each of the five boroughs would rely on different transit modes to evacuate over the course of precisely 3.3 days. Everyone was to flee to “host areas” within 400 miles of the Big Apple. The per-hour capacity of each road out of New York had been carefully calculated; prepositioned bulldozers would help ensure smooth travel, quickly removing disabled automobiles. More than 4.8 million “carless” New Yorkers would be evacuated by subway, train, ferry, barge, cruise ship, and by civilian and commercial aircraft, as well as by more than 20,000 bus trips. Some 75,000 Manhattan residents would travel up the Hudson to Saratoga using three round-trips of five requisitioned Staten Island ferries. Another 300,000 Manhattan residents would travel by subway to Hoboken and be loaded into boxcars for the trip to upstate New York near Syracuse.

As evacuees were flooding into their new “host area,” construction crews—some of them made up of paroled prisoners—would be hard at work transforming the preidentified buildings into fallout shelters, boarding up windows as dump trucks delivered load after load of dirt, and bulldozers and front-end loaders piled the dirt up against the walls; work crews were to spread dirt over building roofs to the required depth using forklifts or bucket brigades. Extensive surveys, physical inventories, and “cubic yards per hour” calculations by FEMA and its predecessors had shown that most parts of the country possessed sufficient heavy equipment to construct and fortify adequate shelters within the three-day time window.

Each host area was expected to absorb five times its normal peacetime population in evacuees and, after registering, all evacuees would be directed to and housed in the various government, community, or commercial buildings identified by the FBI in Project 908. Local families in the “host areas” were to be encouraged to take in relocated strangers as well. “Your neighbors who have evacuated their homes need your help,” FEMA’s preprinted literature explained. “Volunteer now to bring a family to live with you.”

For those who weren’t adopted and lived inside the shelters, conditions were expected to be tight. The plans called for evacuees to sleep alternating head to toe, “the best position for sleep, in that it decreases the spread of respiratory ailments,” explained FEMA’s comprehensive 1981 guide “How To Manage Congregate Lodging Facilities and Fallout Shelters.” Family groups would be placed in the middle of each shelter, with unmarried men and women separated on either side to encourage “high social standards, particularly for sexual behavior.”

In an emergency, the US government intended to pay for all the food and supplies necessary to shelter and feed evacuees across the country—all told about $2 billion a day—although the money might not be available immediately, so private businesses “must maintain complete and accurate records to justify claims submitted after the Crisis Relocation emergency.” Stores, medical facilities, laundries, and other vital necessities would be kept open in host areas for a minimum of 16 hours a day, to ease access, and most would operate 24 hours a day—after all, there wouldn’t be any shortage of available labor.

Many local leaders were understandingly dubious of the FEMA plans—even on paper they seemed difficult to coordinate and implement. In October 1982, as the autumn foliage began to turn in the Green Mountains, local officials from Connecticut journeyed north to Vermont to familiarize themselves with the locations where 653,000 residents of the Nutmeg State would evacuate if plans were activated. In an evacuation, designated local leaders from each “high risk area,” like city council members or county commissioners, would be dispatched to the “host areas” to form provisional joint governments to oversee evacuees and host areas.

Across the state line in New Hampshire, locals in Barrington looked at the pitched roof of their congregational church, some 40 feet off the ground, and wondered exactly how Washington bureaucrats expected them to bury the church under a foot of dirt to provide the adequate fallout protection required for a portion of the 8,900 residents of Monroe, Connecticut, who would be housed in the small town in an emergency. “Damned foolishness,” one local said. And what happened if the nuclear attack came during the roughly one-third of the year when the ground was frozen solid? You couldn’t exactly dig up the dirt then.

As the Cold War ended in the late 1990s, some of FEMA’s deepest secrets leaked into public view. The Washington Post’s Ted Gup broke the news that the agency ran a massive relocation bunker for Congress, hidden underneath the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia. The facility had meeting rooms for the House and the Senate, a cafeteria, medical facilities, and dormitories so elaborately stocked that they even included the prescription eyeglasses for members of Congress. As the Post story ran, the secret FEMA front company that ran the bunker—Forsythe Associates, which purported to be the audiovisual technicians for the resort—rushed to remove the bunker’s small arsenal of weapons: racks of M-16 rifles, M-60 machine guns, and a small contingent of grenade launchers that could have equipped a light infantry platoon. When one Greenbrier executive asked why they were taking away the weapons cache, the head of Forsythe explained that FEMA feared congressional officials would descend on the facility to inspect it—and then raise the obvious question about how FEMA intended to use such weaponry on US soil.

In fact, peacetime operations didn’t come naturally to FEMA. For the Cold War, it had created a special mobile command centers, known as Mobile Emergency Response Support (MERS) units—eventually building some 300 special vehicles and stationing them across the country at its regional facilities. It tried to repurpose them for natural disasters. Following Hurricane Andrew in 1992, FEMA dispatched MERS units to help the residents of hard-hit Homestead, Florida, but found the vehicles were too high-tech to be of much use—the souped-up tractor-trailers could communicate on encrypted channels with military forces around the world but lacked the basic hand-held radios and telephones necessary to communicate with first responders down the street.

US President Bill Clinton, (R), with FEMA Director James Lee Witt, (L), tour a neighborhood hit by the tornado in Birmingham, AL, April 1998. STEPHEN JAFFE/Getty Images

Its inadequate response to those public disasters made it an easy target for attack. And the critics were blunt: After FEMA fumbled its response to Hurricane Hugo slammed South Carolina in 1988, US Senator Fritz Hollings had labeled FEMA “the sorriest bunch of bureaucratic jackasses I’ve ever known.” A year later, after it bungled the response to the Loma Prieta earthquake that disrupted baseball’s World Series in San Francisco, Representative Norm Mineta declared that FEMA could “screw-up a two-car parade.”

The agency’s history as a dumping ground for political patronage did little to help its reputation—just as predecessor civil defense agencies had been parking lots for presidential friends and one-time governors, FEMA had nearly 10 times the normal proportion of political appointees.

In the wake of 1992’s Hurricane Andrew, as FEMA stubbornly waited three days to provide aid to a devastated Florida until officials had filed the correct paperwork, Dade County’s head of emergency preparedness called a press conference and begged, “Where the hell is the cavalry on this one? We need food. We need water. We need people. For God’s sake, where are they?” By the end of President George H.W. Bush’s administration, FEMA was widely seen as the most incompetent agency in the US government. Other government workers labeled it the “turkey farm.”

To reform the agency, President Bill Clinton brought in an old friend—like so many of his predecessors—but that friend turned out to be perhaps FEMA’s most effective leader in its history. James Lee Witt seemed perhaps an odd fit at first. A Skoal-dipping son of a farmer who became known in the capital for his ostrich-skin boots and Southern drawl, he had never graduated from college, but he had a forceful personality and a strong background in emergency management from Arkansas. In short order Witt reshuffled nearly 80 percent of the agency’s senior leadership. FEMA streamlined its public mission to just four priorities that would become familiar hallmarks in the years ahead: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. Witt launched a public relations campaign on Capitol Hill to reassure representatives and senators that their states would get the help they needed.

Quietly, the agency had mothballed relocation sites and put into standby many of its nuclear war preparations—or repurposed them to deal with natural disasters. FEMA updated the MERS command posts to be useful for civilian emergencies and deployed 43 of them to help communications during massive flooding in the Midwest. Even some of FEMA’s fifth-floor at its headquarters near the National Mall, where the classified continuity of government plans were run, was opened up to other projects. Between 1993 and 1994, FEMA’s classified budget dropped from more than $100 million to just $7.5 million as Witt transferred many of its cold war programs into general disaster preparedness efforts.

Meanwhile, the agency was getting downright innovative as well as effective. As part of its response to the Los Angeles earthquake in 1994, it distributed assistance forms right in the daily Los Angeles Times to ensure as many people as possible could access help quickly. And to help boost FEMA’s visibility and power within the federal government, Clinton had promoted FEMA to Cabinet status—meaning it reported directly to the Oval Office.

By the time George W. Bush took over the White House, FEMA had the highest public approval ratings it had ever had—and was publicly known primarily as a natural disaster response agency. “He’s taken a very positive attitude toward the workers,” Leo Bosner, a former FEMA union president said of Witt. “He has focused us on the hazards we face—earthquakes, fires—rather than on what we should do when the bombs start flying.” But for those who knew where to look, FEMA’s continuity of government capabilities had continued to chug along, out of sight. The agency manual, version 1010.1, laid out the responsibilities for its two most generic and innocuous divisions—the Special Programs Division and the Program Coordination Division, the two wings of FEMA that continued to run its secret continuity operations.

In the Blue Ridge Mountains, the FEMA staff continued to keep watch at Mount Weather right through 9/11, when the facility suddenly seemed newly relevant—and Air Force helicopters descended on the mountain, ferrying the congressional leadership and other high-level officials to the bunker.

Just how little had been invested in FEMA was evident inside the agency that day: As the Central Locator System began to track down the presidential successors, it was relying upon Zenith Z-150 computers from the early 1980s.

After overcoming initial communication and response hiccups in the hours and days after 9/11, FEMA eventually earned high marks for the nearly $9 billion in aid it plowed into the New York region. In the wake of the attacks, the White House recruited Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge to launch an Office of Homeland Security, the first step toward the creation of the Department of Homeland Security in 2002. The new department took control of 22 far-flung agencies—from the Treasury’s Customs Service and Secret Service to the Transportation Department’s TSA and Coast Guard to other bodies like FEMA—creating a $36 billion behemoth with nearly a quarter million employees.

The resulting reorganization was the largest government restructuring since the beginning of Cold War when the National Security Act of 1947 had created the modern Pentagon, the CIA, and other entities. The thinking was that by bringing together so many resources focused on domestic security, emergency planning, preparedness, and intelligence, the nation would be more secure and, in a phrase that became a DHS buzzword, more “resilient.” While the Cabinet department—which officially launched on March 1, 2003, with Ridge as its first secretary—was new, DHS was in many ways just the modern incarnation of the Department of Civil Defense that had been advocated by various committees and officials since the 1950s.

Bush’s first FEMA head, Joe Allbaugh, had argued strongly against including FEMA in DHS, believing that having it report directly to the president helped ensure its capability and authority in a disaster—rearranging the deck chairs threatened all the progress the agency had made over the previous decade. But the original plan for placing FEMA inside DHS had been compelling—the 25-year-old agency would become larger, stronger, and more robust, by combining its existing resources with related offices from the Justice Department and the FBI, as well as the Department of Health and Human Service’s National Disaster Medical System. But none of that happened as planned, and the FEMA that became a component of DHS was actually weaker than it had been as a standalone agency.

The DHS reorganization devastated employee morale and cost FEMA its coveted direct access to the president as it was subsumed into a new Cabinet department. The General Accounting Office had warned against the move, saying, “Concerns have been raised that with the emphasis on terrorism preparedness in the aftermath of September 11th, the transfer of FEMA to DHS may result in decreased emphasis on mitigation of natural hazards. Opponents of the FEMA transfer, such as a former FEMA director [James Lee Witt], said that activities not associated with homeland security would suffer if relocated to a large department dedicated essentially to issues of homeland security.”

Within two years of DHS’s creation, that fear came true.

The new focus on terrorism preparedness led FEMA to pour resources into its secret continuity planning—including taking some steps so blindingly obvious that it seemed horrifying that they hadn’t been taken already. In December 2003 FEMA put 300 of its staff through a little-publicized exercise known as QUIET STRENGTH, where its emergency group relocated to Mount Weather. It was the first time that FEMA had ever run a full exercise of even its own ability to notify, evacuate, and relocate its own emergency workers.

The following spring, in May 2004, a much larger FEMA-led exercise, known as FORWARD CHALLENGE, brought together upward of 2,500 federal officials from 45 different departments and agencies to test emergency preparedness procedures. The exercise began with an imagined suicide bombing on the Washington DC Metro, followed by the death of three Cabinet secretaries leaving an event at the National Press Club. Then hackers began an attack on government computers systems, air traffic control networks, and even the nation’s power grid. That evening, a person playing the president activated continuity of government measures.

A FEMA truck sits in floodwaters on the Beltway 8 feeder road in Houston, TX on August 30, 2017. THOMAS B. SHEA/Getty Images

The FORWARD CHALLENGE teams scattered across a reported 100 alternate relocation sites and spent two days running through the nation’s response to such a coordinated attack. “There has never been an exercise of this nature or of this magnitude, even during the Cold War,” bragged FEMA’s head Michael Brown, who under the new DHS reorganization served as both the FEMA chief and the DHS undersecretary for emergency preparedness and response. “Our attempt was to get people focused on plans in the event of another 9/11. You don’t want to wait until disaster hits.”

But it was clear FEMA wasn’t in good shape to respond if a disaster other than a terrorist attack hit. A July 2004 exercise, aimed at responding to a mid-level Category 3 hurricane hitting New Orleans, left agency officials fearful of how poorly FEMA had performed, and DHS budget cuts for the upcoming year left the agency unable to address many of the fixes it wanted to institute.

In the summer of 2004, a year before Hurricane Katrina, senior FEMA officials were warning that the nation’s need to restore balance between the new focus on counterterrorism and more run-of-the-mill natural disasters. “We are now letting terrorism overshadow our preparedness and response to natural disaster,” one official said. Under the Bush administration, the agency had also once again become home to a wide variety of seemingly inexperienced political appointees.

One FEMA union leader complained to Congress, that “emergency managers at FEMA have been supplanted on the job by politically connected contractors and by novice employees with little background or knowledge.” FEMA itself was undergoing an identity crisis, as DHS officials tried to discourage the use of the agency’s initials and instead referred to it as EP&R, the “Emergency Preparedness and Response” directorate for DHS, and its longstanding “Federal Response Plan,” the guidebook for responding to disasters, had been replaced by a DHS-written version known as the National Response Plan that badly blurred lines of authority.

This confusions and lack of focus all came home to roost in August 2005 as Hurricane Katrina churned through the Gulf of Mexico toward New Orleans. The federal government’s response to the hurricane—combined with mistakes at the local and state government level—was an epic disaster in its own right. It triggered the strongest indictment of governmental incompetence of the 21st century. FEMA Director Michael Brown, a one-time horse breeder who lacked any emergency management experience, became a national punchline.

In the end, the only arm of the federal government with the resources, logistics, and manpower necessary to help on a massive scale—the US military—had to step in. The scenes of the swaggering, beret-wearing Lt. General Russel L. Honoré marching into New Orleans restored confidence in an incompetent-seeming national and state government. As the Army commander said himself, he tried to “present a voice of calm and reason when the politicians could not.” And his voice was backed up by hundreds of troops and heavy war materiel. “Brown was a coordinator, not a commander, and had few resources at his immediate disposal. He was a cowboy hat with no cattle,” Honoré said later.

When Barack Obama took control of the executive branch, he tried to restore some of the prestige and emphasis on competence, appointing as FEMA’s head a seasoned emergency manager, Craig Fugate.But he didn’t follow through on his campaign pledge to elevate the job to Cabinet-level. In recent years, FEMA has continued to build out its preparedness infrastructure; it now runs eight major logistics centers scattered across the country, as well as 50 additional supply caches belonging to its National Disaster Medical System and 252 pre-positioned containers of disaster supplies scattered across 14 states. It has nearly 750,000 square feet of warehouses in two locations outside Washington, DC, alone.

The agency’s secret facilities continue to exist in plain sight. On its website you’ll find a fact sheet on “Mt. Weather Emergency Operations Center” that lists a lot of mundane details about its motor pool and 280-seat café but nothing about the massive underground city buried in the greenstone mountain. Instead, it offers a single throwaway line that’d be easy to overlook if you didn’t know what it really meant: “The MWEOC supports a variety of disaster response and continuity missions, mostly classified.”

At Mount Weather, where FEMA still runs regular emergency preparedness seminars and conferences, personnel and authorized visitors can gather in the Balloon Shed Lounge, a little bar in one of the aboveground buildings whose name hints at the facility’s origins as a weather station. There, officials drink beer and wine, eat popcorn, and relax with a game of foosball or pool. Upstairs, a larger cafeteria serves the facility’s masses, both permanent staff and conference attendees alike.

Today, FEMA still spends tens of millions on its continuity programs—the unclassified portion of that budget is around $50 million a year. Mount Weather, whose annual operating costs are more than $30 million a year, is in the midst of what FEMA calls “a significant infrastructure upgrade to replace old infrastructure, correct life/safety items, upgrade IT, and develop a more resilient facility capable of supporting 21st century technology and current federal departments and agencies requirements.” The modern successor to the Emergency Broadcast System, known as IPAWS, last year saw $1.5 million in upgrades for the broadcasting facilities at WLS AM-890, Chicago’s big talk radio station and one of the designated “Presidential Entry Points” for FEMA’s emergency messages. The upgrade is designed to protect the commercial station against an electromagnetic pulse. It is just one part of FEMA’s nationwide broadcast network, which it promises can “reach and communicate with over 90 percent of the US population under all operating environments.”

But it’s clear that the Trump administration isn’t necessarily giving FEMA any more respect than previous administrations: Months before Hurricane Harvey, the administration proposed a budget for DHS that included an 11 percent cut for FEMA to help pay for the border wall.

__________________________________________

Garrett M. Graff (@vermontgmg) is a WIRED contributing editor and the author of Raven Rock: The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself—While the Rest of Us Die (Simon & Schuster, 2017), from which parts of this piece have been adapted and expanded. He can be reached at garrett.graff@gmail.com.

Spread the word