Mathematically it all adds up

All people are equal, but equal to what?

Once you understand there’s a spiritual math

Add soul to the science and subtract the riff–raff

Knowledge ain’t enough, you need funke funke wisdom

—Kool Moe Dee, Funke Wisdom (1991)

Imagine a giant map of the United States with just two words inscribed across it: THE SOUTH. There are no blue states and no red states. Instead, sprinkled across its surface are many clusters of tiny lights marked by names of people, places and events that represent the Black map of America. How, you might ask, can we connect the dots between these points representing James Brown, Sickle Cell Anemia, Ida B. Wells, Mos Def, Zora Neale Hurston, Aretha Franklin, Katrina (the hurricane), Dionne Warwick, Yellow Fever, the Blues, and W.E.B. DuBois, among others?

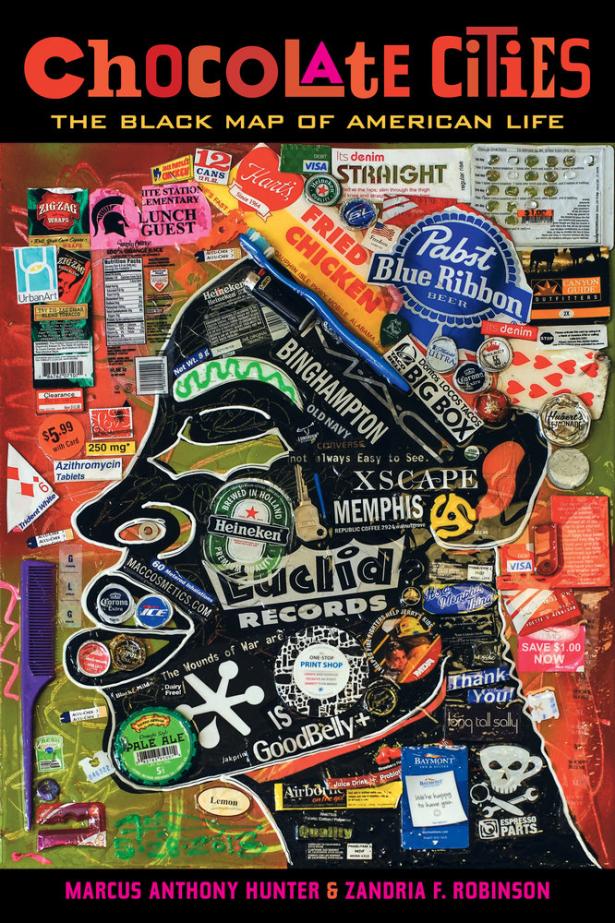

The answers are in Chocolate City: The Black Map of American Life, a very smart new book by two culturally agile sociologists, Marcus A. Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson. They connect these points on the map for us and by so doing offer a vibrant quantified picture of Black migration, survival, cultural production and resistance on American soil.

Adding “soul to the science,” the authors seamlessly combine graphs, maps, census information, Metropolitan Statistical Assessments and community surveys with a vast array of cultural references that run the gamut from Madame C.J. Walker, to Nina Simone, to Assata Shakur, to Biggy and Tupac, to Bounce star Big Freedia to Donald Glover.

The book takes its name from Parliament Funkadelic’s 1975 album featuring George Clinton saying: “We didn’t get our forty acres and a mule, but we got you C C.” Mirroring Clinton’s triumphant proclamation, Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life is neither a cry of despair nor a catalogue of victimization. It is instead an affirmation of the power and persistence of Black people who, in the face of insurmountable odds, continued to migrate, to build, to move their bodies and their homes, to make music and to build Black lives that mattered to them. It is about how Black folks have inhabited places, changed them and clustered densely within them, for safety and community. Ultimately Chocolate Cities is an ode to agency. A work of truth-telling without polemics, this book almost literally breaks new ground, revising our most basic ideas of US geography while questioning the truth claims of social science itself.

Redrawing the map

With equal parts verve and precision, the authors have effectively redrawn the map of the United States, kicking up a whole lot of dust in the process. What this means is that they are exploring not only the racial biases of our geography, but more importantly, our understanding of the way Black Americans build chocolate cities and villages out of a shared sense of “space and place born of language, culture, experience and resistance.” Robinson and Hunter effectively resituate our understanding of what a conventional map represents and misrepresents, helping us to understand that a map is not a fact, it is a stylized fact—a version of reality drawn up by the people who have the power to determine the boundaries of things.

In this way Hunter and Robinson also interrogate the inherent racism of scientific inquiry itself. Science is socially constructed and it is only as enlightened as its practitioners. Racial science (social and otherwise) is rooted in a blindness to its subjects: in the mid 19th century, for example, medical science gave the name Drapetomania to a fictive disease that supposedly afflicted slaves who tried to escape. Well into the 20thcentury, social scientists at Harvard and Yale were measuring the skulls of various ethnics to make the case for “non-whites’” slothfulness, laziness, deviousness and criminal tendencies, thus creating a scientific rationale for racism. Consider if you will Eugenics, The Moynihan Report or even the way some scientists in the early 1980s insisted that AIDS was caused by “poppers”—the party drug of choice at Discos.

Central to Hunter and Robinson’s geographical revision is Malcolm X’s injunction in his 1964 “Ballot or the Bullet” speech:”If you Black, you were born in jail, in the North as well as the South. Stop talking about the South. As long as you South of the Canadian border, you South.” James Baldwin expressed a similar idea when he referred to the North as “up South.” Both Baldwin and Malcolm X were expressing a painful truth about the geography of America.

Because at the end of any day, it is a fact that racism is embedded in the very bone marrow of this country. Consequently, as historian Nikhil Singh has explained in his book Black is a Country, Black migrants “who came North between World War I and the 1960s had their chances curtailed and confined by racial separation…hate strikes, restrictive covenants, urban renewal, red-lining, and Black-busting. Few social groups in human history have experienced the depth and duration of residential segregation that has been imposed on Black internal migrants in the United States.”

The realities that Black migrants encountered as they fled from danger, or searched for greener pastures, are reflected in the names of the regions on the maps in Chocolate City, many of which detail census data reports on Black populations from 1900-1990. On these maps the West becomes West South; the North is Up South; the Middle West is Mid South. What conventional maps dub the South is divided into the Deep South and Down South. Alaska, Oregon, Colorado, North Dakota, Hawaii, Washington State and parts of Northern California become Out South. This renaming is not a series of geographic one liners. These new maps tell the story of how and why Black Americans, in spite of the constant threat of racial violence, fanned out across the nation in search of safety, community, and opportunity.

Hunter and Robinson’s new maps also embody a central truth about America which is that there really is “no moral distance between white Northerners and white Southerners.”

This lack of moral distance will come as bad news to many White “Northerners” who like to believe that there is a moral distance between the regions and who think of racism as a Southern thing. This perhaps helps explain the popularity of such films as Twelve Years a Slave, The Help, and even the far more nuanced Mudbound, which enable Northern white folks to witness white Southerners (usually in the past) running around in white sheets, using the N word and lynching Black people. This also may explain why film a film like Fruitvale Station, about the 2009 murder of Oscar Grant at the hands of the BART police, (in the North and in the present) struggled to find an audience.

Using geography as a way of understanding a whole lot of things, Chocolate Cities illuminates the mechanisms cultural and practical by which “Black people have used the resources at their disposal to change their circumstances and change the places in which they find themselves to make them a bit more amenable for survival, even in places where they are not meant to survive or thrive.” And thrive they did albeit through a world of trouble.

A nexus of interconnected communities

What lies at the core of this book is a celebration of the creativity of Black survival and resistance. Whether it is Aretha’s trajectory from Memphis to Detroit, or the cathartic nature of the blues, or the way that twerking provided a jubilant (and embodied) critique of both the reduction of Black women to their asses and a form of resistance to the idea of Black hypersexuality, the authors created a nexus that forms a larger picture of vibrant adaption within interconnected communities.

The authors ask: ”What has it cost Black people to leave for love or freedom or truth, from one place to another on the chocolate map?” While some migrations represent a hopeful refusal to accept the limitations of race or place, other more brutal journeys are forced. Robinson and Hunter are particularly acute on the multiple jeopardy encountered by members of the LBGT community in their migrations both in and out of the South as they fled homophobia. They point out the way that respectability politics served to erase certain Black heroes and heroines from the historical record, especially Black LGBT Americans. In the section entitled “The Two Ms. Johnsons” the authors focus on the movements of Marsha P. Johnson and Duanna Johnson, two Black trans women born twenty years apart. These women and many others “femme, butch, woman-loving, trans, like all Black people, at all of their intersections,” were “looking for, moving to, creating and demanding places to be Black and Free.”

Katrina – a momentous event on the chocolate map – tells a story of displacement and involuntary migration. Skillfully interweaving the the history of New Orleans, the history of Bounce and the story of the hurricane, the authors’ approach Katrina as a way to express some larger truths about America. First, that Black people, using whatever resources were available to them, have long created “Negrotowns” in forbidden spaces—back-alleys, alongside the tracks, bottoms and lowlands. In “sunken places” to steal a phrase from Jordan Peele. And second, that these Black spaces have remained largely unprotected, or as Kanye opined on national TV in the aftermath of Katrina: “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people.” Forced from their homes, “Black New Orleanians who could move influenced chocolate maps as they made homes out of pain and promise.” After Katrina, Bounce, “part of the city’s sonic landscape” since the early 1990s, became a kind of anthem of “nostalgia, resistance, anger, protest and mourning.”

Whether people displaced by Katrina went to Houston, or Oakland, Nashville or Birmingham, these places were not home. As Frank Ocean says in “A Home Without Houses:”

After ‘trina hit I had to transfer campus

Your apartment out in Houston’s where I waited

Staying with you when I didn’t have an address

F—king on you when I didn’t own a mattress

Working on a way to make it out of Texas

Every night.

Even when Black New Orleanians made it back to their city, the “revitalization” that had taken place in their absence squeezed them into smaller and smaller areas as “rices went up and so did incarceration.”

It is mass incarceration that represents the supreme example of involuntary migration, disproportionately affecting Black men and women who are forced into “chocolate cities of constriction.” This forced march profoundly alters the lay of the land, shattering families, decentering communities and relocating millions of people of color into prison nations where they languish, often far from the families and the chocolate places they called home.

While Chocolate Cities is a story of inventive adaption, fierce survival and Black joy, it is also a history of trauma and communities under siege. This book stands as a witness to the investment of struggle, skill and resources it has taken to build and sustain chocolate cities. It is also a testament to the criminal failure of America to see and honor these essential points on the map.

Read an excerpt from Chocolate Cities.

Mary F. Corey is a Senior Lecturer in American history at UCLA specializing in popular culture. She is the author of The World Through a Monocle: The New Yorker at Midcentury (Harvard University Press) and is currently working on a book about Black Blackface performance, tentatively titled “They Stooped to Conquer.”

Spread the word