What’s This Janus Case All About?

The Supreme Court will decide an important labor case this year, Janus v. AFSCME Council 31. This deals with the requirement in some states that workers represented by a union must pay either union dues, if they are a union member, or otherwise a “fair share” or “agency” fee, a slightly lower amount that covers the costs of bargaining and representation. Mark Janus, a child support specialist for the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, objected to this fee. He claims that all of the union’s work is like lobbying that is inherently political in nature. Thus the required fee forces him to support political speech by a union he disagrees with, which is a violation of his First Amendment rights. This interpretation is contrary to the Supreme Court’s Abood v. Detroit Board of Education decision of 1977 which allowed agency fees. The Supreme Court voted 4–4 on the similar Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association case two years ago, and with the addition of conservative justice Neil Gorsuch, everyone and their anti-union uncle anticipates a ruling for Janus and against the union. This would extend the “right to work” framework to all public sector workers nationwide.

I apologize right now for using the “right to work” phrase, a misleading but brilliant piece of anti-union propaganda that the labor movement has struggled with for many decades. But it’s how folks generally talk about this issue, so I’ll stick with it, calling it RTW. It originated from the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 which allowed states to ban union contracts that require the payment of union dues or agency fees. Anti-union groups promoted this as a “right to work” without being forced to pay union fees. Unions dislike RTW because they have a requirement to represent all workers in a bargaining unit and RTW allows workers to become free-riders, receiving the benefits of the union without any of the costs. RTW also weakens the labor movement overall. If workers opt out of membership, it reduces the funding for unions and erodes workplace solidarity, hurting the struggle for better wages, benefits and working conditions. This is exactly what anti-union RTW promoters want.

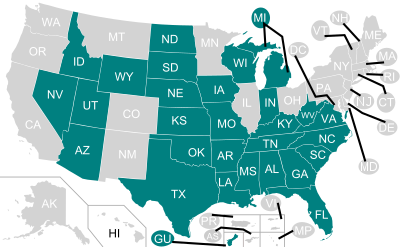

Many states adopted RTW laws in the decade after Taft-Hartley and a number of other states have done so in the last decade as well. Currently there are 28 RTW states, shaded darker on this map.

The Supreme Court recently heard arguments for the Janus case and there has been a lot of hyperbolic press coverage that an anti-union ruling could be devastating for unions because of a mass exodus of members. I don’t think that’s true, but let’s take a look.

How Many Workers Will Quit their Unions?

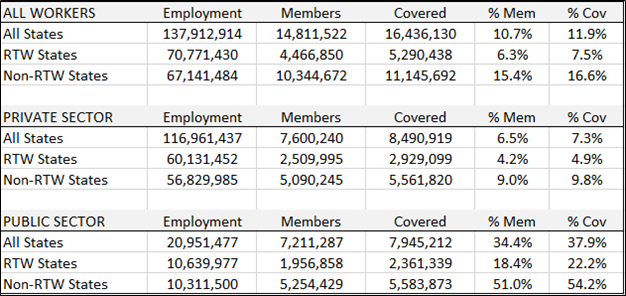

So RTW means workers can quit the union and pay nothing. But how many public sector union members are likely to drop their membership and become free riders? Well let’s review the data and make some estimates. The chart below shows the 2017 data on union membership and union coverage from UnionStats.com, which compiles data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics survey.

Let’s review definitions first. Here are the survey questions, from the BLS Technical Note:

On this job, are you a member of a labor union or of an employee association similar to a union? If the response is “no” to that question, then the interviewer asks a second question: On this job, are you covered by a union or employee association contract? If the response is “yes,” then these persons, along with those who responded “yes” to being union members, are classified as represented by a union. If the response is “no” to both the first and second questions, then they are classified as nonunion.

So the survey asks if the worker is a union member, and if not, are they coveredby a union contract. If they are, this generally means they are a non-member under a RTW scenario.

In the following chart, the % Mem is the percentage of workers who are union members and % Cov is the percentage who are covered by a union contract. The latter number is slightly higher because, as we know, some workers are covered by the contract but have opted out of union membership.

This chart also breaks out the private and public sector data, and aggregates all the RTW and non-RTW states together. It’s no surprise, we see that the % Mem and % Cov numbers are much higher in the non-RTW states. In fact, they are about double in the private sector and more than double in the public sector.

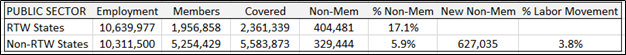

Now, we want to use this data to make an estimate of how many public sector workers in non-RTW states may drop their union membership after the Janusdecision. We can estimate that by looking at another number, the % of covered workers who are not members. The chart below looks at public sector data only, and shows a few new columns, the Non-Mem and % Non-Mem. Non-Mem is just the difference between the number of workers who are covered and members. These would be the covered but non-member workers. The % Non-Mem is just the percentage of the total covered workers. What we see is that in RTW states, we have overall, about 17% of union workers who have opted to be non-members. In non-RTW states, unsurprisingly, that number is much lower, about 6%.

I admit I’m a little surprised that these numbers are fairly low. If the BLS survey data is correct, even in RTW states, unions hold onto over 80% of their members. One reason the non-member percentage is higher in RTW states is that these are mostly more conservative states with anti-union politics which will negatively affect workers’ attitudes toward unions. But the other reason of course is that these workers are allowed to pay no union dues or fees whatsoever. That’s the central goal of RTW, and it works. It’s an incentive to free ride on the benefits of the union contract without paying your fair share. And of course this reduces the funding for unions in those states which makes organizing and bargaining more challenging, exactly what the RTW advocates want.

So to estimate the number of workers in non-RTW states who will drop their union membership, we can start by assuming that the % Non-Mem will rise to the RTW level, from 5.9% to the higher 17.1%. That 11.2% increase of the 5.6 million non-RTW covered workers yields about 627,000 workers who will drop their union membership and thus pay no union dues.

This is of course a huge loss. For comparison, the labor movement gained about 171,000 workers in 2017, and that was a relatively good year compared to most. This loss is well over three times that. But let’s keep it in perspective. Compared to the size of the labor movement, it’s only 4.2% of the 14.8 million union members. That’s hardly a disaster.

It Might Be Worse or It Might Not Be so Bad

Perhaps the number of quitters will be larger than that. The Janus decision will be momentous, indeed one of the most important Supreme Court labor decisions in decades. It will get a lot of press and many union members will hear about it. Moreover, we can expect the National Right to Work group (a Mark Janus supporter) and other anti-union groups to advertise this news widely to reach as many union members as possible with advice on how to drop their membership. As an example, a group called the Freedom Foundation has been contacting union members in Oregon to convince them to quit. Increased efforts like this may raise the number of workers who leave their unions. More workers in current RTW states may also leave their unions. Additionally, some bargaining units may become so weak that if enough workers quit, they will be susceptible to union decertification, where the entire group of workers becomes non-union. Anti-union groups will continue working to spread RTW to the private sector as well. So it could get even worse for unions.

Or perhaps the number of quitters will be smaller than that. There’s the possibility that because these are the more liberal, pro-union states that will make the switch to RTW, fewer workers will opt out of union membership. Moreover, unions have, at some level, been preparing for this decision for years and can be expected to work harder to convince members to stay. If it comes down to a continuous argument between unions and anti-union groups about the importance of union membership, unions have a very strong case and should be able to win most of the time. Fairness, collective action and solidarity are compelling issues. It may not be so bad for unions.

The Double Face of Janus?

This leads to some possible unintended positive consequences of the Januscase. OK hear me out. It will be the biggest change in labor relations in decades and a jolt for the labor movement which may be inspired to fight harder and more creatively to hold and expand its membership. Recent commentary proposes that the spread of RTW could create more labor relations “chaos”, which in some ways may be good for the labor movement. There is a traditional historical trade-off of agency fees for a no-strike agreement during the union contract. Without the fees, unions may want to keep the right to strike at any time. Unions may experiment more, for example, trying to end exclusive representation, kick out the free riders, and represent only their members. There’s also the intriguing possibility that the First Amendment argument could backfire on the anti-union folks and help unions by bringing new protections for their bargaining activity. We’ll have to see.

But mostly, unions would have an incentive to increase their militancy to defend their contracts and make new gains. After all, the best way to build a strong and united union membership is to fight and win, as the West Virginia teachers have recently demonstrated. They remind us that even in a RTW state, where the teachers don’t even have collective bargaining rights, a strong and successful strike is possible. And in this effort, rank and file activity is key and unions should never “third party” themselves, where they talk about “the union” as if it’s something separate from the members. The union is the members and that has to be real.

So the expected anti-union Janus decision is bad news. But it is unlikely to be a disaster for unions, and in an era of declining union density, may even be the wake-up call that they need. Janus is the Roman god of transitions, and this may be a big one for the labor movement.

Eric Dirnbach is a Labor Movement Researcher, Activist, Campaigner, Organizer, Educator & Writer, based in New York City. @EricDirnbach

Spread the word