The first sign that something was wrong was a continuous busy signal on the home phone of Doug and Peggy Ryen.

Bill Hughes, who lived nearby, wasn’t initially concerned. His 11-year-old son, Chris, had slept over at the Ryens’ and he thought maybe they had all gone out for breakfast. But finally at noon Hughes drove over to pick Chris up and, when no one answered the Ryens’ door, he peered through the sliding glass doors — and his brain couldn’t process all the red. “This is paint, makeup,” he thought wildly.

Then reality sank in, and he kicked the kitchen door in. Blood from the five victims was splattered everywhere. Hughes rushed to his son, but the body was cold. Doug and Peggy Ryen, both nude, had also been stabbed to death, and the bloody corpse of their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, was in a doorway. But Josh Ryen, 8 years old, was moving feebly on the floor even though his throat had been slashed and his skull fractured.

Soon sheriff’s deputies were swarming all over the Ryen house in affluent, suburban Chino Hills, east of Los Angeles, that day in June 1983. Several signs, including Josh’s personal account, pointed to three white attackers, and blond or brown hairs were found in the victims’ hands, as if torn off in a struggle.

Sheriff’s deputies were also contacted by the woman whose boyfriend was a convicted murderer, recently released from prison, whom she suspected of involvement in the Ryen killings. She not only gave deputies his bloody coveralls but also told them that his hatchet was missing from his tool rack and resembled one of the weapons reportedly used in the attacks.

But instead of testing the coveralls for the Ryens’ blood, the deputies threw them away–and pursued Cooper. After a racially charged trial, he was convicted of murdering the Ryens and Chris Hughes and is now on death row at San Quentin Prison.

Gov. Jerry Brown is refusing to allow advanced DNA testing that might finally resolve the question of who committed the murders, even though Cooper’s defense would pay for it. Brown refuses to allow even advanced testing of the blond or brown hairs that were found in the victims’ hands.

This is the story of a broken justice system. It appears that an innocent man was framed by sheriff’s deputies and is on death row in part because of dishonest cops, sensational media coverage and flawed political leaders — including Democrats like Brown and Kamala Harris, the state attorney general before becoming a U.S. senator, who refused to allow newly available DNA testing for a black man convicted of hacking to death a beautiful white family and young neighbor. This was a failure at every level, and it should prompt reflection not just about one man on death row but also about profound inequities in our entire system of justice.

I’m using strong language, I know. But I went to San Quentin to interview Cooper, reviewed trial transcripts and other documents, spoke to innumerable people on and off the record, and in 34 years at The New York Times, I’ve never come across a case in America as outrageous as Kevin Cooper’s. So hear me out.

Smarter people than me have come to the same conclusion. “This guy is innocent,” said Thomas R. Parker, a 30-year law enforcement veteran who was deputy head of the F.B.I.’s office in Los Angeles. “The evidence was planted, he was framed, the cops lied on the stand.”

Parker said the case involved “abject racism,” and he has volunteered his time investigating the case for the last seven years because he is horrified that a man he believes was framed is nearing execution.

Or listen to Judge William A. Fletcher of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. “He is on death row because the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department framed him,” Fletcher declared in a searing 2013 lecture.

This appears to be a replay of a tragedy we’ve seen before: The police are under great pressure to solve a sensational crime, they are sure they have the culprit, and when evidence is lacking they plant it and give false testimony. This is called “testilying,” and it’s more common than we’d like to think. In New York City alone, The New York Times found “an entrenched perjury problem,” with more than 25 instances of probable testilying just since 2015.

How did we get here?

Initially, the authorities searched for three white men, which fit the evidence from the crime.

The coroner initially determined that there had been several assailants using a hatchet, an ice pick and either one or two knives to stab and slash the murder victims some 140 times.

Peggy Ryen was strong and athletic and kept a loaded pistol in the bedside drawer, directly beside where Doug’s body was found. Doug was a 6-foot-2 former Marine and military policeman. His loaded rifle was in the closet behind his body.

It seemed that there must have been several attackers to use multiple weapons, overpower the Ryens and keep them from getting to their guns — not a lone 155-pound individual like Cooper.

The evidence from the Ryen home and testimony from Josh pointed to three white perpetrators.

Over the course of the investigation, several witnesses claimed they had seen three white men in a car resembling the station wagon stolen from the Ryens’ home the night of the murders.

Several other witnesses said they saw three disorderly white patrons at the Canyon Corral Bar late on the evening of the killings wearing bloody clothing, in a car that may have been the Ryens’.

The men were surprised when the blood was pointed out — and afterward two bloody shirts were found nearby.

But none of this ultimately mattered to the sheriff’s office after deputies made what they thought was a breakthrough discovery: A 25-year-old black man convicted of burglary had escaped from a minimum-security Chino prison by walking through a fence.

And he had holed up for two days in an empty house just 125 yards from the Ryens’ home.

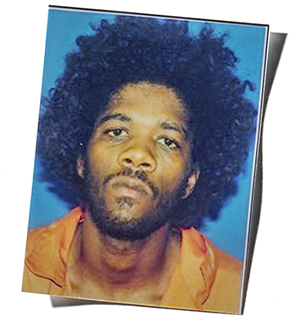

That was Cooper, and deputies who examined his file and mug shot saw a black man with a huge Afro who fit their narrative of an incorrigible criminal. He had a long arrest record dating back to when he was 7 years old.

The sheriff’s deputies were sure they had their man: an escaped felon, one who they thought looked suitably evil. The authorities pivoted and focused on Cooper, ignoring other threads.

Still, the authorities had a problem: Although they were sure Cooper was the killer, they couldn’t find fingerprints, hairs or other evidence implicating him.

So evidence began to turn up in mysterious ways.

Two deputies searched Cooper’s hide-out on June 6, a day after the Ryens’ bodies had been found. The police didn’t find anything suspicious in the house.

The next day, deputies searched the hide-out again, now having identified Cooper as their primary suspect. A bloody green button from a prison uniform materialized on the floor along with a hatchet sheath. (Eventually, it turned out that Cooper had been wearing a brown jacket, not green.)

Deputies claimed they had not entered that room before. But later, one deputy's fingerprints were found inside the closet, indicating he had been in the room — and had lied about it.

Or consider the Ryens’ station wagon.

It was found in Long Beach, 30 miles away, and inconveniently had blood on the driver’s seat, the front passenger seat and the back seat — suggesting at least three killers.A bloody hatchet was also found near the Ryen house, probably thrown out of the station wagon window — on the passenger side.

Areas with blood found in Ryens’ station wagon

A thorough search of the station wagon found no evidence that Cooper had used the car. That problem was remedied when a second search of the vehicle turned up some of Cooper’s cigarette butts; sheriff’s deputies had found such cigarette butts in the empty house where he had stayed, but the butts had vanished.

Another challenge for the prosecution was motive. After escaping from the prison, Cooper was desperate for money, yet some cash had been left on the counter in the Ryens’ house.

The prosecution suggested that Cooper wanted to steal the station wagon. But the Ryens kept the keys in the car; there was no need to enter the house.

Nevertheless, four days after the discovery of the murders, the sheriff announced the crime had been solved: Cooper was being sought for murder.

While the police were desperately trying to connect Cooper to the crime, another man who should have been a prime suspect was not being investigated.

That’s a remarkable element of this case: Not only has the evidence against Cooper largely been discredited, but evidence has accumulated against another individual, who happens also to be a convicted murderer. Fletcher, the federal judge, wrote a long section in a judicial opinion implicating this man, whom I’ll identify only by his first name, Lee.

It was his girlfriend, Diana Roper, who had alerted deputies after the murders made the news to the reasons she believed that he had participated in the Ryen murders.

Roper and her sister said that Lee came home late on the night of the killings in a station wagon like that of the Ryens, wearing blood-drenched coveralls, and that his hatchet was missing from his tool rack and resembled one of the murder weapons described by authorities. She said that on the day of the killing she had laid out for Lee a medium-size tan Fruit of the Loom T-shirt with a pocket; she remembered because she had just bought it for Lee at Kmart. It was exactly like a Fruit of the Loom T-shirt found by the bar with blood on it; testing showed it was the Ryens’ blood.

Roper said in an affidavit : “Lee was wearing long sleeve coveralls … splattered with blood. … He did not have the beige T-shirt. Lee took the coveralls off and left them on the floor of the closet. … A few days after, … Lee had changed his appearance by cutting most of his hair off and trimmed his sideburns and his ‘Fu Manchu’ moustache.”

Roper gave deputies the bloody coveralls. But instead of testing them to see if the blood was from the Ryens, the sheriff’s office threw them out.

Roper said she cannot be sure that Lee’s missing hatchet is the same as the one used in the murders, but she added that “the curvature of the handle is the same” and it had a similar “American Indian pattern to it.” Her sister, Karee Kellison, who was with Roper, confirmed much of her story.

Then there was the peculiar matter of the recovery of the Ryens’ station wagon.

The station wagon didn’t turn up until a week after the killings — near the home of Lee’s stepmother in Long Beach.

But Cooper had made his way south to Tijuana, Mexico. He arrived there the evening after the killings.

The sheriff’s office claimed that Cooper took the Ryens’ station wagon, but aside from the witnesses who reported seeing several white men driving it on the night of the murders, a new witness has emerged who saw the car the next day.

The woman, who is scared of being identified as a witness for now but says she will testify under oath if necessary, said three white people in the Ryens’ car were driving crazily and almost crashed into her vehicle.

Her grandmother, who was with her that day, wrote down the license plate number. Hours later, after the murder was discovered, the authorities broadcast a description of the missing car with its license plate number.

“I ran out to the car and got the slip of paper on which my grandmother had written the license number,” the woman wrote in a formal declaration. “It was exactly the same.” She said that she wrote to the police with her information, but the authorities did not follow up or share it with the defense.

Shown an old photo of Lee, this woman said that it resembled the driver but that she couldn’t be sure it was the same man.

If there’s no apparent motive for Cooper, there are only hints of one for Lee. His previous murder, of a 17-year-old girl, was at the behest of a gang leader, Clarence Ray Allen, who raised the same kind of Arabian horses as the Ryens. There’s some — very squishy, unconfirmed — evidence that Allen may have previously threatened to kill Peggy Ryen, that they had a quarrel over a horse sale gone sour, and that she was terrified of him.

All this said, let’s be clear that if there’s one lesson from the Cooper case, it’s that we should be very wary of assuming guilt on the basis of fragmentary evidence. I tracked down Lee, now 68, and he strongly denied any involvement in the case. However, he did not want to discuss it and asked not to be contacted again.

One point in Lee’s favor: He has avoided serious tangles with the law in the decades since the Ryen killings.

With all these uninvestigated threads, it’s worth considering the motives of the San Bernardino sheriff’s office, which handled the investigation.

Sheriff Floyd Tidwell had recently been appointed to his position and was facing election that year, adding to the pressure to solve the most brutal crime in the county’s memory.

It’s clear that the sheriff’s office wasn’t a stickler for rules. Tidwell was later convicted for stealing more than 500 guns from county evidence rooms. A lab technician who “found” shoe print evidence against Cooper was later fired for stealing heroin from the evidence room.

The sheriff’s office also bungled the forensics, so that 70 people trampled through the crime scene.

Then, a day after the bodies were discovered, the district attorney closed the on-scene investigation for fear, he said, of gathering so much evidence that defense experts could spin complicated theories.

Concerns with the San Bernardino sheriff’s deputies have continued since then.

Almost exactly 10 years after the Ryen murders, there was another terrible murder in San Bernardino County, and a man named William Richards was convicted in part based on evidence “discovered” by the same sheriff’s office lab technician who earlier had “found” evidence against Cooper. Later, it turned out that this evidence was planted, and Richards was eventually exonerated. (The sheriff’s office declined to comment for this article.)

The only witness to the murders themselves, of course, was Josh Ryen, who endured a physical and emotional trauma that is unimaginable. By the time of the trial, he had no clear memory of what happened or of seeing an intruder.

Yet his first memories were clearer. I tracked down Don Gamundoy, who at the time of the murders was a social worker at the hospital to which Josh was rushed. “He was awake and alert,” Gamundoy recalled.

Josh could hear but couldn’t speak because of the wound to his throat, so Gamundoy wrote the alphabet, the numbers and the words “yes” and “no” on a piece of paper and asked Josh to point to the letters to spell his name, phone number and birth date. Josh did so correctly, showing that the method worked.

Then Gamundoy asked Josh if the people who did this were black.

“He pointed to ‘no,’” Gamundoy told me. Communicating in the same way, Josh said that the attackers were white, and that there were three or four of them.

This was a chaotic scene unfolding as doctors were struggling to treat the boy, but Gamundoy said he had asked each question twice to make sure the answers were not a mistake. Sheriff’s deputies were present and observing, he said, and in interviews with deputies later, Josh referred to the attackers as “they,” saying that “they” had chased him.

With a good defense, Cooper might have prevailed. But his county public defender was overwhelmed and made a series of practical legal mistakes.

“Kevin got convicted because they framed him and because he didn’t have a half-decent defense,” said Norman C. Hile, his current lawyer. Hile, now retired as a partner in the international law firm Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, has volunteered on the case for the last 14 years because he fiercely believes in Cooper’s innocence.

This is a familiar pattern: Inmates have third-rate defenders at trial, but after they are sentenced to death they get the help of brilliant free counsel; by then it is often too late to undo the damage.

Cooper’s trial unfolded amid the ugliest racism. At a hearing, a crowd displayed signs reading “Hang the Nigger.” One man displayed a noose around a stuffed gorilla.

Newspapers carried inaccurate reports, apparently based on prosecution leaks, that tied Cooper to the murder scene and suggested falsely that he was gay (seizing upon 1980s homophobia as well as racism).

Still, the trial outcome was close. The jury took a week to convict Cooper, and one juror told reporters that there would have been no conviction “if there had been one less piece of evidence.”

Cooper was scheduled to be executed at 12:01 a.m. on Feb. 10, 2004. On Feb. 9, he was offered a last meal (he turned it down), and led on the “dead man walking” path to a holding area beside the execution cell. He was strip-searched, given new clothes to die in, and guards searched his arms for veins that could be used to administer lethal injections. A pastor visited to pray with him.

Yet on what was supposed to be his last day, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit granted a stay of execution, and a few hours before the end, the warden halted the machinery of death.

Cooper was now permitted to conduct a new test on the tan T-shirt, and this time the labs found something extraordinary. Yes, that may have been Cooper’s blood on it — but the blood had a chemical preservative called EDTA in it. That suggested that the blood came not from Cooper directly but from a test tube of his blood. Sure enough, the sheriff’s deputies had taken a sample of Cooper’s blood and had kept it in a test tube with EDTA.

Now the lab checked a swatch of blood from that test tube. More wonders! The test tube miraculously contained the blood of two or more people.

This indicated that the sheriff’s office may have used the test tube of Cooper’s blood to frame him, and then topped off the test tube with someone else’s blood.

Cooper’s case began to get traction. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals en banc refused to hear an appeal by Cooper, but Fletcher wrote a remarkable 100-page dissent, concluding, “The State of California may be about to execute an innocent man.” Four judges joined in this extraordinary judicial opinion.

Likewise, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights found in 2015 that there had been profound flaws in the case and called for a review. The deans of four law schools and the president of the American Bar Association expressed concerns. At the end of his term in office, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger urged a “thorough and careful review” of the case.

Five of the original jurors signed declarations expressing concerns about the case and calling for new DNA testing or for clemency. An award-winning book, “Scapegoat,” concluded that Cooper had been framed. In February 2016, Hile and the Orrick law firm submitted to Governor Brown a 235-page clemency petition, pleading for advanced DNA testing of evidence from the case.

Cooper’s lawyers ask above all for new “touch DNA” testing — capable of detecting microscopic residues — of the tan T-shirt, the hatchet and the blond or brown hairs found in the victims’ hands. This might determine who wore the tan T-shirt or handled the hatchet, and whom the hairs came from. Was it Kevin Cooper? Or was it Lee?

As state attorney general, Kamala Harris refused to allow this advanced DNA testing and showed no interest in the case (on Friday, after the online publication of this column, Senator Harris called me to say "I feel awful about this" and put out a statement saying: "As a firm believer in DNA testing, I hope the governor and the state will allow for such testing in the case of Kevin Cooper."). As for Brown, he has not responded in the two years since the petition was filed, and he refused to be interviewed. His spokesman, Gareth Lacy, told me that the petition “remains under review.” Brown leaves office in January, and I think he is running out the clock.

One reason Brown may be hesitant to weigh in: For four years before becoming governor, he was attorney general, and during that time he suggested that no one on death row was innocent. I hope that this won’t keep him from allowing advanced DNA testing.

California voters in 2016 approved a ballot measure to hasten executions. So, depending on how litigation unfolds, Cooper could again be led to the execution chamber sometime in the next year or so — and even if he delays execution, he feels he is wasting away.

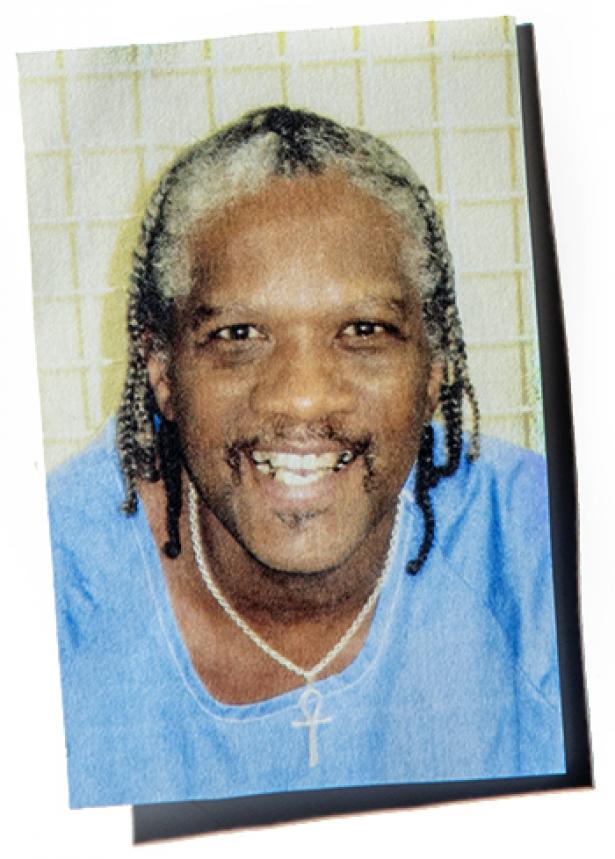

“Look at how white my hair is,” Cooper told me, bending over to show how his hair is graying. “I don’t have as much time left. Every day is one I won’t get back.”

I was speaking to him in San Quentin Prison, in a cage where inmates are allowed to meet outsiders. Cooper lives on death row in San Quentin, in a 4.5-foot-by-11-foot cell.

Cooper told me about his abusive and troubled childhood in Pennsylvania, where he was adopted as a baby. When prosecutors said that Cooper had tangled with the law since the age of 7, they were right, but he says that the reason is that he was running away from home to escape beatings. His childhood involved shoplifting, marijuana smoking, juvenile detention and negligible education; he never graduated from high school.

These days in prison, Cooper has remedied his lack of education with a G.E.D. diploma and comes across as smart, passionate and articulate. But he’s not optimistic that the governor or courts will block his execution.

“I don’t have any confidence,” he told me. “I don’t believe in the system.” He also spends his time writing a memoir, which now stands at more than 300 pages. “That’s my motivating factor to get out of here, to tell my story and tell the truth about this rotten-ass system,” he said.

I asked Cooper whom he blamed. The sheriff? The jury? “I blame myself first and foremost, for walking out of Chino prison, for letting those people get their hands on me,” he said. “I regret that every day of my life.”

Time and again, Cooper came back to a larger point: The criminal justice system is unfair to poor people and members of minorities.

“I’m frameable, because I’m an uneducated black man in America,” he said. “Sometimes it’s race, and sometimes it’s class.”

“The only people here on death row to my understanding are the poor,” he added. “Even the white people on death row, they’re poor. If they’re white, racism goes away and classism jumps in and takes its place.”

Although Cooper’s defenders note that before the murders he had never been convicted of a violent offense, or even charged with one, it’s a bit more complicated: He has been accused of rape without being charged.

I’m particularly troubled by one episode. Cooper admits forcing a 17-year-old girl into a vehicle in 1982. She says that he also hit her, threatened to kill her and raped her, and she went afterward to a hospital to seek treatment; he flatly denies hitting or raping her. Hile says that if the evidence had been strong, Cooper would have been charged with rape. For my part, I can’t think why the girl would have lied, and although it’s impossible to know after 36 years what happened, it bothers me.

It’s obvious to you by now that this is not a usual column — I’m not sure The Times has ever published a column of this length — so why am I exploring the case with such passion? I became interested primarily because Fletcher and other respected federal appeals judges had said he was framed. That just doesn’t happen.

I’m also haunted by something else. In 2000, I proposed reporting a lengthy piece about doubts about the conviction of Cameron Willingham, who was then on death row in Texas for the arson murder of his three children. An editor talked me out of it, and I never did write about Willingham, who was executed in 2004. Since then, growing evidence has emerged that he was innocent, and perhaps it’s partly to atone for my earlier failure that I’ve taken up Cooper’s case.

If Cooper is innocent, he would have plenty of company. The Death Penalty Information Center says that since 1973, at least 162 people sentenced to death have been exonerated. One peer-reviewed study estimated that at least 4.1 percent of those sentenced to death in the United States are innocent; that would mean that on California’s death row alone, where 746 people await execution, about 30 have been wrongfully convicted.

Moreover, there’s abundant evidence that executions in America are linked to race: One study in Washington State found that jurors were three times as likely to hand down a death sentence for a black defendant as for a white defendant in a similar case.

Decades after Cooper’s trial, many of the people involved have died or didn’t want to talk to me. Some who were willing to talk insist that the trial was fair and Cooper was properly convicted.

William Baird, the sheriff’s office lab expert who in 1983 found suspicious shoe print evidence supposedly linking Cooper to the crime scene, told me that the evidence was real. He acknowledged having stolen heroin from the evidence room but said that had nothing to do with the evidence against Cooper.

I also spoke to Bill Hughes, who discovered the bodies of the Ryens and of his son, Chris. He is certain that Cooper is responsible: “There is no doubt in my mind that he did that.” His wife, Mary Ann, is equally passionate: She spoke of her family’s suffering as the case drags on without closure, of her certainty that Cooper is simply trying to distract from overwhelming evidence against him, of her frustration at calls for further testing when there has already been forensic testing for 35 years.

I told Bill and Mary Ann Hughes that my heart breaks for them. And of course, I can’t be sure that Kevin Cooper is innocent. One lesson to absorb from the criminal justice system’s past mistakes is that we need some humility about our own ability to ferret out truth.

That’s why the governor should allow advanced DNA testing, especially of the hairs and of the T-shirt and hatchet, and why Dianne Feinstein, Gavin Newsom and other California politicians should back the call.

I know readers will ask me what they can do, and I don’t have a good answer beyond contacting Brown’s office or signing a petition calling for clemency. Another takeaway is to regard our criminal justice system, especially in its interactions with the poor or racial minorities, with greater skepticism.

Maybe in the grand scheme of things, the fate of one man on death row doesn’t seem so important; innumerable people die tragically every day. Yet we aspire to be a nation where we are all equal before the law, and if we execute a man in so flawed a case without even bothering to test the evidence rigorously, then a piece of our justice system dies along with Kevin Cooper.

Governor Brown, if you’re reading this, I understand that you may believe that Cooper is guilty. But other smart people, including federal judges and law school deans, believe him innocent. So how can you possibly execute him without even allowing advanced DNA testing, at the defense’s expense, to resolve the doubt? What’s your argument for refusing to allow testing?

The former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor once wrote that “the execution of a legally and factually innocent person would be a constitutionally intolerable event.” She’s right: It is not just Cooper’s life that is at stake, but also the legitimacy of our system of laws. This is a test of Governor Brown, of our justice system, of our politicians, and of us.

“This is bigger than me,” Cooper told me in our prison meeting. “This is bigger than any one person.”

See the original article for interactive visual online illustrations weaved into this essay.

Spread the word