On July 16, 1979, the worst accidental release of radioactive waste in U.S. history happened at the Church Rock uranium mine and mill site. While the Three Mile Island accident (that same year) is well known, the enormous radioactive spill in New Mexico has been kept quiet. It is the U.S. nuclear accident that almost no one knows about.

Just 14 weeks after the Three Mile Island reactor accident, and 34 years to the day after the Trinity atomic test, the small community of Church Rock, New Mexico became the scene of another nuclear tragedy.

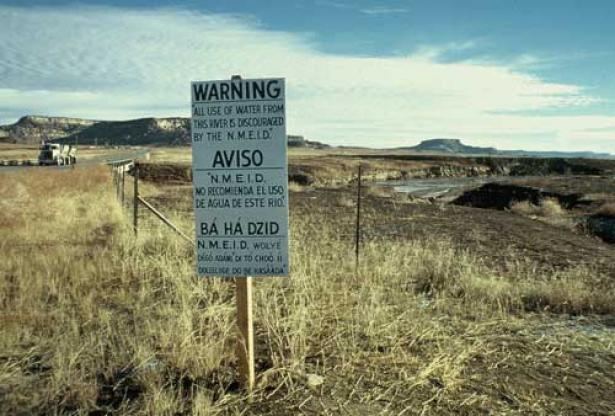

Ninety million gallons of liquid radioactive waste, and eleven hundred tons of solid mill wastes, burst through a broken dam wall at the Church Rock uranium mill facility, creating a flood of deadly effluents that permanently contaminated the Puerco River.

No one knows exactly how much radioactivity was released into the air during the Three Mile Island accident. The site monitors were shut down after their measurements of radioactive releases went off the scale.

But the American public knows even less about the Church Rock spill and, five weeks after it occurred, the mine and mill operator, United Nuclear Corporation (UNC), was back in business as if nothing had happened. Today, the Church Rock accident is acknowledged as likely the largest single release of radioactive contamination ever to take place in U.S. history (outside of the atomic bomb tests).

Why is the Church Rock spill – that washed into gullies, contaminated fields and the animals that grazed there, and made drinking water deadly – so anonymous in the annals of our nuclear history? Perhaps the answer lies in where it took place and who it affected.

Church Rock was a small farming community of Native Americans, mainly Navajo, eking out a subsistence living off the arid Southwestern land. Nearby, several hundred million gallons of liquid uranium mill tailings were sitting in a pond waiting for evaporation to leave behind solid tailings for storage. On the morning of July 16, 1979, part of the dam wall collapsed, releasing a roaring flood of radioactive water and sludge.

It was both a predicted and preventable failing. But steps were never taken to avert the disaster. UNC CEO, David Hann, in later Congressional hearings, described the accident as “a risk, and we undertook this.” Several state regulatory agencies had remained silent in the face of warnings by UNC’s own consultant that the dam, as constructed, was vulnerable.

When UNC was required to “clean up” the mess, the company completed removal of just one percent of the spilled tailings and liquids. Stagnant pools, where children played, were found to have levels of radiation 100 to 500 times natural background. Sheep and goats were too contaminated to eat. Wells and other drinking water sources were shut down.

However, the accident happened “far from civilization” in a remote area inhabited by possibly the most poverty-stricken and disenfranchised community of people in the country – Native Americans. The massacres and smallpox blankets were over, but another deliberate act of racially-based discrimination – the avoidable radioactive contamination of the Navajo community and likely well beyond it – went unpunished and largely unreported.

Today, the Three Mile Island Accident is remembered, marked and rightly alluded to as a further example of the deadly risks of nuclear power. Wrongly, it is also referred to as this country’s only major nuclear accident. Rarely is the Church Rock anniversary either known or noted. The long-term effects of this enormous level of radioactive contamination are not yet fully measurable given that health effects resulting from radiation exposure can take decades to appear and can affect future generations.

Native American lands in the Southwest are riddled with disused uranium mine and mill sites. The communities have observed high levels of kidney diseases and cancers. Yet only one population-based epidemiological study of health effects associated with uranium mining has ever been conducted on the Navajo Nation. No health study has ever been carried out in the Church Rock area.

Instead, Uranium Resources Inc., (URI) which took over the property from UNC, applied to open a new, in-situ leach uranium mine at Church Rock. But a state groundwater discharge permit for the project was terminated in March 2016. Without it, the mine could not go forward. It was a rare victory. As Larry King of Eastern Navajo Diné Against Uranium Mining, said at the time, his people “live every day with environmental legacy from past uranium mining.”

But it wasn’t over. A Canadian company, Laramide, acquired URI. Exploratory drilling will resume at Churck Rock and at Crownpoint, just 30 miles from Church Rock. The goal, says Laramide, is to “to satisfy New Mexico Environmental Department Groundwater Discharge Plan requirements whereby Laramide must demonstrate in a laboratory environment the ability, post leaching, to restore groundwater in the mining aquifer to an acceptable level.”

History is only waiting to repeat itself.

[Linda Pentz Gunter is the editor and curator of BeyondNuclearInternational.org and the international specialist at Beyond Nuclear. She can be contacted at linda@beyondnuclear.org.]

If you’d like to be the first to read stories like these, sign up for our Monday email digest. We will send you a very brief synopsis of the new stories on our site, with links to read them and learn more. Sign up today!

Spread the word