By the time Arthur Harris Jr. turned 17, he had already endured a childhood of grinding poverty in Hartford’s North End, the death of his mother, and the rejection of a community that viewed homosexuality as a sin. It should have come as no surprise to anyone, then, that he went searching for love and acceptance wherever he could find it — a search that landed him in the arms of a man nearly twice his age and, later, in the kinds of risky situations he’d been warned about in his high school health class.

“I was looking for love like everybody else,” says Harris, now 26. “I thought the gay lifestyle would be a safe place.”

But it wasn’t safe. Like thousands of other young, black men, Harris contracted HIV before he was 18. The virus, which can lead to AIDS if untreated, disproportionately affects African-Americans nationwide.

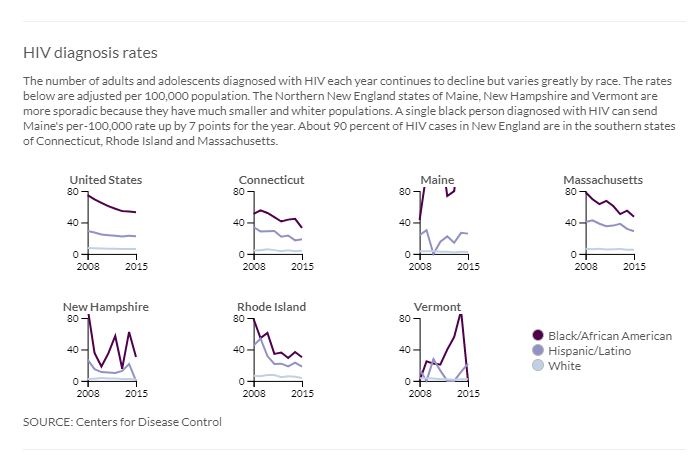

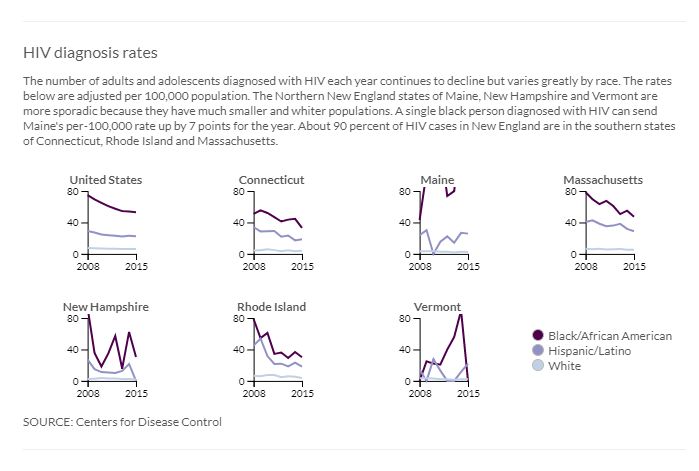

This stubborn racial disparity persists in Connecticut and in neighboring New England states despite years of work to undo it, according to a Connecticut Mirror analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Black males in Connecticut were around nine times as likely as white males to be diagnosed with HIV in 2016, the latest year for which diagnosis data are available, on par with the national disparity that exists between the two groups.

This disparity is especially prominent among men like Harris — black men who have sex with other men.

While the lifetime risk of HIV is around one in 99 for all Americans, the CDC projects that the risk for black men who have sex with men could grow to a staggering 50 percent, if trends continue. That compares with a lifetime risk of one in 11 for white gay and bisexual men, one in 20 for black men and one in 48 for black women.

This disparity is intertwined with some of society’s most persistent and inflexible social problems, according to experts. These include racial discrimination, incarceration, poverty and lack of access to health care — as well as higher rates of some sexually transmitted diseases, smaller sexual networks and lack of awareness of HIV status.

“There are significant health disparities within communities of color which fuel this epidemic,” said Shawn Lang, deputy director of AIDS Connecticut, adding that the disparities are complicated by a distrust of medical providers and the failure on the part of some providers to routinely screen for HIV and other STDs.

The problem is worsened, she said, by the effects of homophobia.

“Homophobia in those communities is often colored by culture and religion,” Lang said. “Conversations about sex, in general don’t happen, forcing the young men to stay closeted to their families and communities.”

A decade ago, Dr. Cato Laurencin, a UConn Health orthopedic surgeon and researcher, analyzed the disparities and called for action in a medical journal article. This June, Laurencin and his team conducted additional research and published another article in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities that showed the trends highlighted 10 years ago continued and, in some instances, have worsened.

“It’s really important that we create an all-hands-on-deck situation,” Laurencin said. “There are still views toward men having sex with men which are negative in certain segments of the black community. We need to start being non-judgmental, put away our prejudices, put away our predilections in order to address this issue.”

Two years after Laurencin’s initial article was published, Harris sat in a Hartford clinic as a cotton swab was swiped underneath his upper lip to test for HIV. After 20 minutes, he had his results.

“My whole world was shattered,” recalled Harris. A slender man with a quiet demeanor, Harris has chosen to speak publicly about his diagnosis in the hopes of helping others. On his chest, the word “Fearless” is tattooed in a flowing script.

As he sat on the hard clinic chair eight years ago, however, his brain jammed on two questions.

“How did this happen to me? Who did this to me?”

The impacts of race

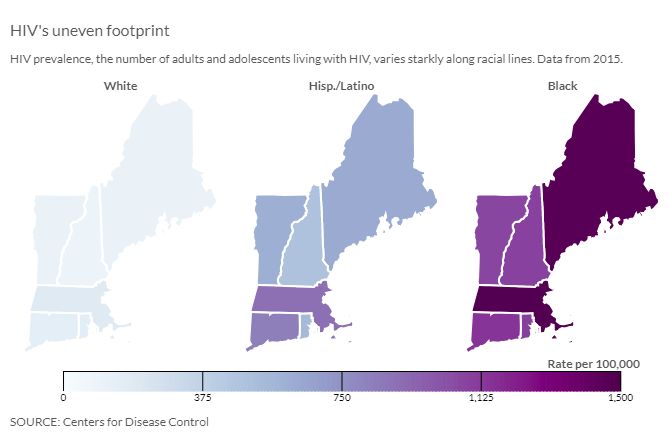

Nationwide, around one million adults and adolescents live with diagnosed HIV, including 36,000 in New England, according to CDC data. Fewer people have been diagnosed with HIV year after year but, despite that progress, the disease affects people of color far more than whites.

The overall prevalence rate for HIV — the number of people living with HIV — was around 363 per 100,000 nationwide in 2015, the latest year for which prevalence data are available.

The impact of the disease, however, is vastly uneven across racial lines.

The nationwide black prevalence rate was 1,238, and the Hispanic and Latino rate was 497. Meanwhile, the rate among whites was 174.

In Connecticut, where black males are about nine times as likely as white males to be diagnosed with HIV, according to 2016 data, Hispanic males were more than four times as likely as white males to be diagnosed with the virus.

Those racial disparities were present a decade ago, indicating that efforts to lower HIV rates are not effective enough in the black and Hispanic communities.

In the June article, Laurencin and his team recommended a five-fold plan to address the racial disparities in HIV rates. The plan, which is intended for health care practitioners and advocates, includes working to eliminate prejudices and unconscious biases when treating patients, and employing new technology and techniques to help prevent or eradicate HIV/AIDs in the black and Hispanic populations.

The team also called for the reduction of secondary factors, such as incarceration rates, poverty, STDs and other circumstances that increase the chances of contracting HIV.

“The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community continues to be of crisis proportion,” the team wrote. “While higher rates of poverty and prevalence of negative socio-economic determinants in African-Americans are important underlying factors, we believe that a concerted, re-dedicated effort (as can be seen with other national health emergencies such as opioid addiction) can create meaningful change in the decade to come. The understanding of the intersectionality between all of these factors is necessary to finding a solution to eradicate this epidemic.”

Citing a 2012 brief by the Center for American Progress, Laurencin and his team also single out racism and the societal inequalities that accompany it, such as residential segregation, as one of the primary underlying factors in HIV rate disparities. People living in low-income, primarily minority neighborhoods, they note, are significantly less likely to receive early HIV testing and treatment, for example.

In the June article, Laurencin and his team recommended a five-fold plan to address the racial disparities in HIV rates. The plan, which is intended for health care practitioners and advocates, includes working to eliminate prejudices and unconscious biases when treating patients, and employing new technology and techniques to help prevent or eradicate HIV/AIDs in the black and Hispanic populations.

The team also called for the reduction of secondary factors, such as incarceration rates, poverty, STDs and other circumstances that increase the chances of contracting HIV.

“The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community continues to be of crisis proportion,” the team wrote. “While higher rates of poverty and prevalence of negative socio-economic determinants in African-Americans are important underlying factors, we believe that a concerted, re-dedicated effort (as can be seen with other national health emergencies such as opioid addiction) can create meaningful change in the decade to come. The understanding of the intersectionality between all of these factors is necessary to finding a solution to eradicate this epidemic.”

Citing a 2012 brief by the Center for American Progress, Laurencin and his team also single out racism and the societal inequalities that accompany it, such as residential segregation, as one of the primary underlying factors in HIV rate disparities. People living in low-income, primarily minority neighborhoods, they note, are significantly less likely to receive early HIV testing and treatment, for example.

LaToya Tyson, associate director of prevention at AIDS Connecticut, is blunt when asked about the underlying reasons for the disparity in HIV rates.

“The big elephant in the room is the racism,” she said. “That in itself plays a huge part in how the system works with clients … If black and brown bodies don’t actually have as much validity in the system, then the things that happen to those bodies are irrelevant.”

Forgive, but not forget

Harris grew up in crowded apartments in Hartford’s North End, sleeping on living room floors. At school, he was quiet and soft spoken, and relentlessly bullied by his peers for being gay, even though he hadn’t come out yet.

His mother — who bought him his first radio and taught him how to braid hair — died in a car accident when he was 12. Her death, just as Harris was entering puberty, was a colossal blow to a young boy grappling with the knowledge that he was different from his peers.

When he was 16 and a sophomore at Thomas Snell Weaver High School in Hartford, he told his family he was gay. Not all of his family members reacted well to the news, Harris said, which was painful.

Harris was taught about HIV in his high school sex education class, so he knew he needed to use condoms when he started having sex. He remembers being terrified of contracting the virus.

After he was diagnosed, Harris narrowed down the time he contracted HIV to one of two incidents, both of which occurred when he was 17.

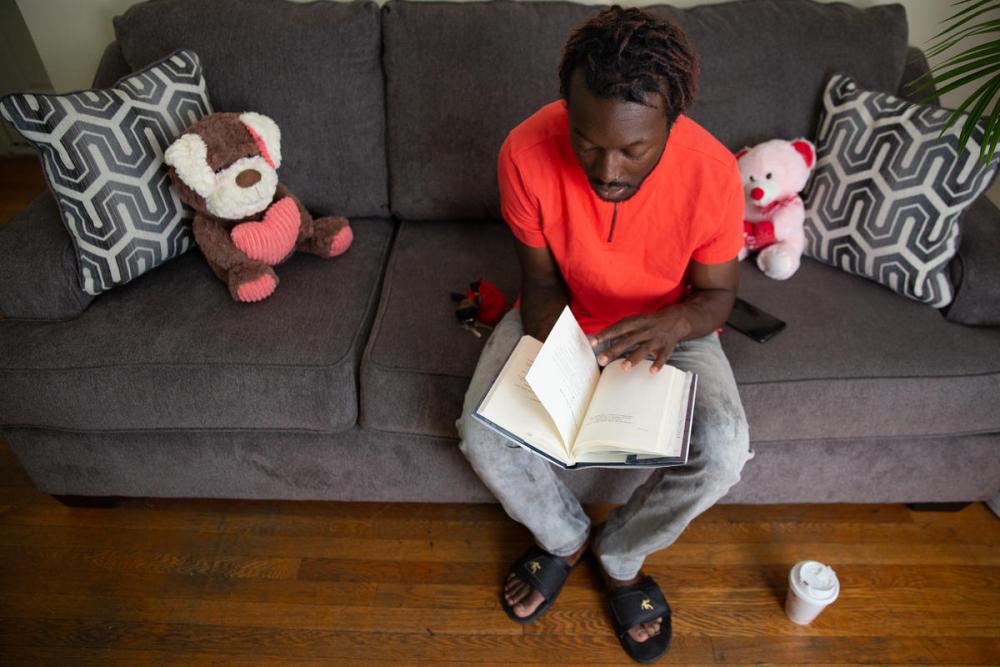

Arthur Harris Jr. CREDIT RYAN CARON KING / CONNECTICUT PUBLIC RADIO

In the first incident, Harris said, he went to a hotel with his partner of several months, who was about twice his age, and had sex. There were other men in the hotel room, but Harris said he didn’t have sex with any of them. Eventually, his partner left him in the hotel room alone, so Harris called a friend. His friend found Harris blacked out in a parking lot after he had been drinking that night.

Harris later learned that his partner, whom he trusted, hadn’t used a condom that night. He thought he had.

In the second, Harris said he connected with a gay couple online and went to visit them at their apartment. He says now that he thought he was just going to hang out, and maybe make some new friends.

One of the men kept insisting that they have sex, but Harris refused.

“He kept pushing himself on me,” Harris recalled recently. “I told him I didn’t want to do it … I was drinking, I couldn’t push him off. I felt helpless.”

Harris blacked out and when he woke up, he said, he was being raped.

Harris told his mentor at True Colors, a nonprofit in Hartford that provides services to LGBTQ youth. His mentor told him that he should get tested for HIV, so they went to the local clinic, where he received the swab test. Days later, he got blood work, which confirmed the diagnosis.

Dr. Cato Laurencin CREDIT PETER MORENUS / UCONN PHOTO

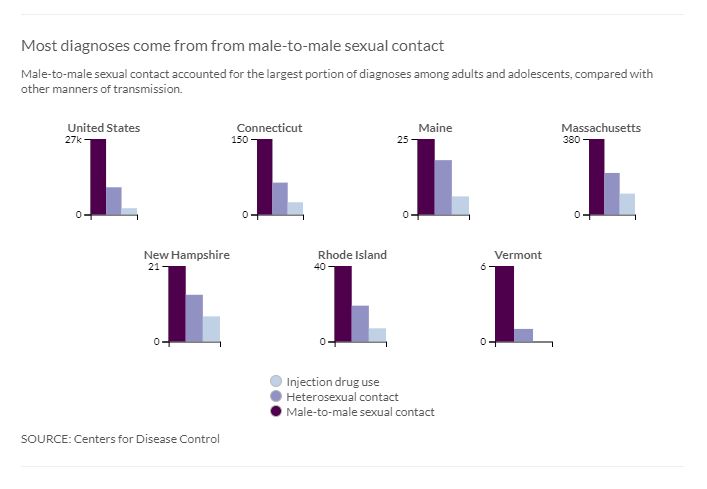

Within the black population nationwide, nearly 80 percent of the HIV cases among black males and adolescents in 2016 were attributed to men who have sex with men. There were 10,223 HIV cases among black men who have sex with men in 2016, up 154 percent since 2005, according to Laurencin’s article.

In Connecticut, more than 60 percent of HIV diagnoses in 2016 were transmitted by men having sex with men, also known as MSM, compared with other manners of transmissions, the Mirror found. The number of diagnoses from men having sex with men has not decreased since 2008, and all of the progress in reducing Connecticut’s overall diagnosis rates has been among heterosexual contact, injectable drug use and other causes.

“I believe that HIV infections amongst MSM are still high and refuse to decrease as much as they could because MSM of today do not have the experience of the MSM of yesteryear,” said Tyson, who has worked in HIV prevention for nearly two decades.

“When this infection began, in its onset, there were deaths, weekly deaths, several funerals every week, and the MSM of that time watched their friends, their family, their loved ones dying consistently around them,” she said. “That’s not the case anymore. The MSM community now are aware of HIV. They are aware that they don’t want it. They are aware of the ways to protect themselves to stay healthy.

“What they are not as aware of is the history behind how we’ve gotten to where we are today in HIV treatment. They are unaware of the true devastation that HIV can actually cause,” she concluded.

Lang said another issue in the field is a lack of resources to ramp up efforts in prevention, care and housing.

“Funding has been stagnant or cut over the past decade on the state and federal levels. We’re consistently having to do more with less,” she said. “We’re seeing the consequences in the rise of new infections, many of whom are what we call ‘late testers,’ meaning they don’t get routinely tested,” she added, “and when they do — it’s usually due to a health problem — they get an AIDS diagnosis within a year.”

The statistics are equally grim for black men who have contracted HIV. The CDC reported in February 2017 that only 48 percent of African-American gay and bisexual men effectively suppress HIV with consistent medication, and the numbers are even lower for black men who has sex with men in their late teens and 20s. In 2014, one in five black men having sex with men had progressed to AIDS by the time they learned of their infection, according to the Laurencin article.

Harris, however, is determined this will not happen to him. Months after his diagnosis, Harris started receiving treatment at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. That’s where he met Ty Waterman, a case manager with the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and the UConn Health Pediatric, Youth and Family HIV Program.

Harris eventually opened up to Waterman and told him about the two incidents in which he could have contracted the virus. Together, they called the police to report the rape. Waterman said the police came and talked to Harris alone, but that he never heard anything come of the report.

Waterman, now 40, worked with Harris for about three years and recalled recently that, even in Harris’ darkest hours, the young man wanted to share his story — and his HIV status — even though many in his life were telling him to stay silent.

Although Harris was initially shy and timid, Waterman said, he became more confident and outspoken as he matured and became more educated about HIV — primarily because he wanted to prevent others from contracting the virus.

“Most of the youth I encountered in field were outspoken, but quiet about their status,” Waterman said. “Arthur was soft and fragile, but roaring about his status. He did not want anyone to be put in his predicament. Arthur always worried about others before himself.”

Harris started off by telling a few friends and now his Facebook cover photo says in bold letters, “HIV POSITIVE.”

Arthur Harris Jr. CREDIT RYAN CARON KING / CONNECTICUT PUBLIC RADIO

These days, Harris finds joy through writing poetry, drawing, listening to music, and spending time with his dog, Brady, and his fiancé, to whom he recently proposed.

He stays at his fiancé’s apartment in the West End of Hartford a few days a week — and the rest of the week at the St. Elizabeth House, transitional housing for the homeless in Hartford, where he’s lived for a year and a half.

In his fiancé’s one-bedroom apartment, a clear glass plaque sits on the mantle, displaying Harris’ GPA at Goodwin College, where he graduated in 2014 with a bachelor’s degree in human services.

To stay healthy, Harris takes one prescription, Stribild, every day to keep the virus suppressed.

Eight years after his diagnosis, Harris said, he is not angry that he has HIV.

“I had to forgive the people that did it to me,” he said. “Forgive, but not forget.”

Connecticut’s efforts

The Connecticut Department of Public Health recently announced the launch of “Getting to Zero,” a campaign to prevent all HIV infections, AIDS-related deaths, and HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.

The campaign will be launched in the five cities with the highest number of people living with HIV: Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, Waterbury and Stamford.

A 23-member commission appointed by DPH Commissioner Raul Pino, comprised of advocates from the at-risk populations in each city, AIDS service organization representatives, local health advocates, people living with HIV, and researchers from New Haven and Hartford, is currently collaborating with the health directors of the state’s five cities.

This summer, listening sessions will be held in each city to learn from community members what barriers exist that prevent or inhibit the effective delivery of HIV services to the impacted populations.

The commission will then develop specific recommendations for “Getting to Zero” in each city. A final report will be presented to the commissioner in December.

For years, DPH has been tracking and targeting HIV disparities in communities across the state. In 2012, the department disseminated nearly 1,500 posters and placed advertisements on Metro-North train platforms.

The posters featured black men between the ages of 18 and 64.

The men wanted to share their stories — some were HIV positive, others were HIV negative, and some weren’t sure of their statuses. The campaign led to community forums in two black churches in Waterbury, according to DPH.

Harris also wants to be part of the solution. He plans on creating his own public service announcement videos, featuring his personal story, to post on his Facebook page.

“It will convey a message,” he said. “No one in the community is really advocating and we need education to the public to kill the stigma of what the face of HIV is.”

The data and analysis code for this report are available here.

CT Mirror Data Intern Jamie Kasulis contributed to this report.

This series is a collaboration between The Connecticut Mirror, Connecticut Public Radio, and the New England News Collaborative.

Spread the word