The 2019 mayoral race has revived prospects of an African-American and Latino led rainbow coalition in Chicago and stands as a watershed election in the city’s history. No matter the outcome of next week’s run-off election, Chicago will once again have an African-American mayor—either Lori Lightfoot, former federal prosecutor and chair of the Police Accountability Task Force, or Toni Preckwinkle, president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners and chair of the Cook County Democratic Party. The question remains, however, what this will mean for the continuing quest for African-American and Latino socioeconomic and political parity with whites in Chicago.

Will the outcome signal a new chapter for a “rainbow coalition” that is committed to the needs and interests of the majority minority population, or will it be a sign of the rainbow’s end? We believe that the seismic shift in the coalition between African-Americans, Latinos and progressive whites in Chicago may signal the rise of an African-American led coalition that is unbeholden to the needs and interests of Chicago’s racial minorities. The African-American quest for a black mayor will finally be fulfilled, however will stand in direct contrast to Harold Washington’s monumental victory.

The prospects for an African-American and Latino political coalition have loomed large since the 1980s. It was thought that the marginalized socioeconomic status of both groups relative to whites, and their histories of oppression, made them natural allies in an attempt to gain political influence over the spoils of local politics—jobs, contracts, and city services. Reality however, has challenged this assumption. Black and brown alliances have been shown to be less cooperative than originally believed.

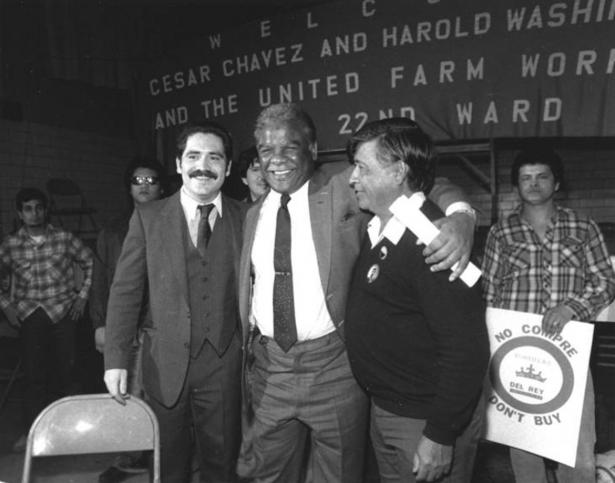

The rainbow coalition that elected Harold Washington was primarily led by the African-American community, with Latinos and North Lakefront whites serving as junior, albeit necessary, partners against entrenched white racial interests. In the wake of Harold Washington’s sudden death in November of 1987 the coalition began to unravel and by 1989 it had completely torn asunder. The first rupture occurred within the African-American community, and subsequently affected the viability of an African-American and Latino Coalition. In the absence of strong and reliable African-American political allies, the Cook County Democratic party was able to bring Hispanic leadership into a coalition designed to curb the power of the African-American electorate.

Harold Washington was the glue that held warring factions within the African-American community together. Absent his leadership, all the gains associated with his mobilization effort were short-lived. The African-American electorate, as the leading partners in the Washington coalition, has been tremendously hampered by its lack of political discipline and political savvy. In all but one mayoral race since 1991, blacks have competed against one another, rather than support a single candidate in the primary and general elections.

After his successful bid for mayor in 1989, Richard M. Daley adroitly exploited the political split within the African-American community. As Monroe Anderson, former press secretary for Eugene Sawyer, notes, “Daley essentially [made deals with] black politicians who could win contracts and made power-sharing agreements with them so they could swing the opposition his way.” A key strategy to gain the support of the African-American electorate involved support for Black ministers. As Fredrick C. Harris describes, “as a political entrepreneur who needed to make inroads into Chicago black communities, Daley would use political patronage as a way to induce black clergy to support his candidacy and political goals.”

The weakness of the African-American electorate is an irony, given that Chicago has successfully mobilized to elect two U.S. senators—Carol Mosely Braun and Barack Obama—and groomed the first African-American president. Sadly enough however, divisions, distrust and again, a lack of political savvy, prevent their political influence in the city.

In 2011, Rahm Emanuel won election in a crowded field of African-American and Latino candidates. The presence of three African-American and two Latino candidates in the race spoke volumes about the prospects of an African-American-Latino alliance.

In the 2015 race, Congressmen Bobby Rush and Luis Gutiérrez backed Rahm against a crowded field including two African-Americans and a Latino candidate. In the end, Emanuel defeated Jesús “Chuy” García, garnering 56.23 percent of the total vote. The limited ability of the African-American and Latino communities to forge a rainbow coalition was most evident in the support that Emanuel received from the African-American and Latino communities: 57 percent of the vote in black-majority wards and 39 percent from majority-Latino wards.

The 2015 election illuminated two very troubling realities: the limited influence of prominent African-American and Latino leaders and the unwillingness of African-American and Latinos to ally, in spite of their shared powerlessness. Shared marginalization is not enough, particularly in the presence of division and distrust.

Chicago is now a very different city than it was in 1983 when Harold Washington was elected as Latinos and African-Americans are approximately equal in number. Since 2000, the African-American population has declined by 250,000.

Chicago population by race/ethnicity, 2017

| Number | Percentage | |

| Whites | 893,334 | 32.9% |

| African-American | 797,253 | 29.3% |

| Latino | 787,978 | 29.0% |

| Asian | 179,176 | 6.6% |

| Total | 2,716,462 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2017). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race American Community Survey 1-year estimates.

The rise in the Latino population has increased competition for jobs, contracts, and services, and have resulted in infighting between groups. Nowhere is this fissure more apparent than in disagreements among African-Americans about Emanuel’s proposal “to spend $1.1 million to provide city-issued IDs for undocumented immigrants,” and to offer “sanctuary for undocumented immigrants, aid to their “Dreamer” children, and refuge to Puerto Rican families displaced by Hurricane Maria.” As Laura Washington reports, “some African-Americans are saying our communities are in peril. What about sanctuary for us? Where are our dreams? “we” are citizens. “Them” not so much.”

Another critical difference since Washington’s 1983 victory, is a decline of white racial animus and opposition to electing a racial minority. In the 1983 general election between Harold Washington and Republican party candidate, Bernard Epton, whites gave Epton approximately 81 percent of their vote in an attempt to defeat Washington. This was not the case in the 2019 race, with the majority-white wards casting 60 percent of its votes to minority candidates.

In the nearly 32 years since Washington’s death, both the African-American or Latino communities have failed to manifest mature, disciplined politics. And we must ask who are the real political brokers in the African-American and Latino communities?

Racialized voting in the 2019 primary was most prominent among majority African-American wards. Latinos split their vote equally among white, African-American, and Latino candidates. African-American wards, on the other hand, gave an overwhelming majority of their vote—75 percent—to the six African-American candidates in the race. In doing so, for the first time since the election of Harold Washington, the majority African-American wards departed from delivering the majority of its vote to a white candidate. In the 2019 election, the top white challenger, Bill Daley, won a mere 9.62 percent of the vote from majority African-American wards.

Proportion of ward by candidate race, Feb. 26, 2019 election

| Majority Black Wards Gave … | Majority Latino Wards Gave … | Majority White Wards Gave … | |

| Black candidates (6) | 75% | 35% | 46% |

| Latino Candidates (2) | 8% | 32% | 14% |

| White Candidates (6) | 17% | 33% | 40% |

Source: Chicago Board of Election Commissioners

Fourteen of the eighteen majority African-American wards gave a plurality of their vote to a candidate who couldn’t win. Wilson, an African-American self-made millionaire, received 77 percent of his vote from the African-American community. The majority-white and Latino wards, on the other hand, gave Willie Wilson 2.9 percent and 4.54 percent of its vote, respectively. Wilson, subsequently endorsed Lori Lightfoot, which was unexpected given his close ties to the African-American religious community.

Although no white candidate was successful in the primary election, the white vote will likely be the largest determinant of who will win, and white power brokers will still likely lead the governing coalition, as the next mayor scrambles to navigate the myriad problems left in the wake of the Daley and Emanuel administrations. The aldermanic races in the Feb. 26 election are a case in point. Although not on the ballot, newly elected millionaire governor, J.B. Pritzker and Mayor Rahm Emanuel contributed nearly $1 million to incumbent aldermen, making them “two of the largest campaign contributors overall to aldermanic candidates.”

The pertinent question about African-American-Latino political coalitions is less about whether they will exist, but rather, whether they will bring economic parity to African-American and Latino communities in Chicago. Population shifts in the city of Chicago have rendered African-Americans and Latinos fully capable of electing a “rainbow” candidate. However, neither Lightfoot nor Preckwinkle were the favored candidates of the majority of African-American or Latino wards.

African-Americans and Latinos comprise 58 percent of the total population in Chicago. They are 62 percent of the registered voters, however majority African-American and Latino wards represented 54 percent of the total votes cast in the 2019 primary. percent of total votes cast in the 2019 Feb. 26 election.

Total/Proportion of votes casted by ward type, 2019 primary election

| Number | % of Registered Voters | % of Total Turnout | |

| Majority African-American Wards | 180,909 | 31% | 34% |

| Majority Hispanic Wards | 107,258 | 31% | 20% |

| Majority White Wards | 242,022 | 39% | 46% |

| Total | 530,190 | 34% | 100% |

Source: Chicago Board of Election Commissioners

The next mayor will confront challenges that Washington did not have. Chief among these challenges are a public pension crisis, uneven development, the continuing need for police reform, budget shortages, infrastructure needs, and under-resourced schools in African-American and Latino communities. It remains to be seen whether she will be able to balance downtown business interests with the needs of Chicago’s African-American and Latino residents. There will no doubt be tension between resource demanding and resource generating populations, and to be sure, the coalition that elects the next mayor will not be a Harold Washington rainbow coalition.

Valerie Johnson is associate professor and chair of the political science department at DePaul University. Her work focuses on urban politics, African-American politics and urban education.

Robert T. Starks is Professor Emeritus at Northeastern Illinois University’s Jacob Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies in Chicago. He studies and teaches black politics and black studies.

Donate to The Chicago Reporter. Support Journalism that Confronts Race, Poverty, and Income Inequality.

Founded on the heels of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, The Chicago Reporter confronts racial and economic inequality, using the power of investigative journalism. Our mission is national but grounded in Chicago, one of the most segregated cities in the nation and a bellwether for urban policies.

The Reporter is the nation's only nonprofit news organization whose mission is to investigate race. That was true in 1972, and that is still true today. We use data to show how the policies of government and private institutions affect racial inequality, and we hold policymakers accountable. We report from the viewpoint of the people and communities affected by these policies. And we practice journalism that informs change and solutions.

We need your support to continue to produce our trademark, investigative journalism on race, poverty, and income inequality. If you value our work, make a donation today.

Click here to make a tax-deductible donation.

Spread the word