n 1856, the new Republican Party ran its first candidate for President, the western explorer John C. Fremont. He was an unusual leader for an unusual party. The Republicans’ aggressive antislavery platform, which proclaimed bondage a “relic of barbarism,” was the first of its kind for a major party in US history.

Opponents denounced the Republicans as sectional fanatics who would split the Union. Equally dangerous, their hostility to human property threatened the foundations of the social order, even beyond the slaveholding South. “Fremont,” as one conservative rallying-cry had it, was synonymous with “free-soil, free-love, and communism.”

Popular enthusiasm for Fremont — who was, of course, no real hero — was unmistakable. Republican mass meetings and rallies covered the Northern states, bringing crowds of twenty thousand or more to unlikely places like Beloit, Wisconsin, and Massillon, Ohio.

Yet the new party faced long odds at the polls. Four years earlier, the antislavery Free Soil Party candidate for president had won less than five percent of the national vote.

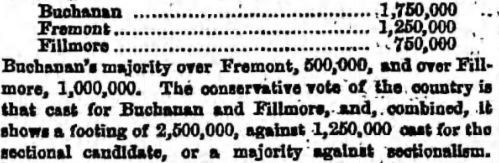

And in November 1856, Fremont was defeated by the Democrat James Buchanan. In purely electoral terms, it was a comfortable victory: Buchanan won 19 of 31 states, topping Fremont (and nativist candidate Millard Fillmore) by 12 percent in the popular vote. Down the ballot, meanwhile, the Democrats picked up 50 seats in the House of Representatives and reclaimed control over both chambers of Congress.

Some Republicans sought consolation in the idea that they had achieved a “victorious defeat,” winning eleven free states and proving that an aggressive antislavery party could compete in national politics. But the hard fact remained that Buchanan, not Fremont, was poised to enter the White House. Democratic commentators in the press, who claimed the election result as a conservative triumph, urged clueless Republicans to #FeelTheMath.

“Mr. Buchanan’s election,” declared one Maine newspaper, was now “a fixed fact.” Republican efforts to claim victory in the face of defeat only showed “a lack of correct knowledge of mathematics. They wriggle and squirm like a serpent pinned to the earth,” refusing to acknowledge that Fremont’s downfall was “the death-knell of Black Republicanism.”

Another widely shared analysis used numbers to underline the point: “The joint vote of Buchanan and Fillmore — that is to say, the conservative vote of the country,” dwarfed Fremont’s support by over two to one. The United States remained a center-right nation.

A host of nineteenth-century Nate Silvers emerged to perform yet more sophisticated operations on the voting data (then as now, these chiefly involved multiplication and division). The New York Journal of Commerce observed that Fremont won a clear majority only in six small northern states, comprising “but little more than one-seventh of the whole population.”

Republicans might argue that Fremont’s showing represented a historic breakthrough for antislavery politics, but in truth his support was highly circumscribed by geography and demographics. “Fremontism,” the Journal concluded, was “predominant only in New England and a little strip of the country settled chiefly by New Englanders, on the borders of Canada and the lakes.”

Alas, pundits lamented, these stubborn facts would do little to sway Fremont supporters. “The black republican organs in New-York,” scoffed the Washington Union, “are famous as arithmeticians.” Blinded by their extremism, Republicans would continue to insist that the 1856 campaign marked an advance, not a retreat, for the larger antislavery struggle.

Veteran election-watchers were sure they knew better. Buchanan had won, and Fremont had lost: that was the bottom line. “The people are tired of black republicanism,” crowed the Union. After “the beating they have received,” joshed one Albany ancestor of Carl Diggler, “it is time that the Fremonters should change their names… black-and-blue republicans.”

In 1860, of course, these same Republicans swept the North and elected Abraham Lincoln president. With antislavery forces now in command of the government, southern slaveholders chose to flee the Union. Less than a decade after Fremont’s blowout loss at the polls, slavery was destroyed and American politics revolutionized.

Yet they missed the deeper significance of the Fremont campaign, which showed that an aggressive antislavery party could win mass support in the free states. Republicans were right to call the election of 1856 a “victorious defeat.” It stands today as the outstanding example of a historical moment that brought a marginalized social movement from the radical fringe to the center stage of American politics.

Matt Karp is an assistant professor of history at Princeton University and a Jacobin contributing editor.

If you like this article, please subscribe or donate to Jacobin

Spread the word