IN THE LAST WEEK OF APRIL, nearly 23 percent of all traffic to news sites tracked by web analytics firm Parse.lycame from search engines. Google alone accounts for nearly half of external referral traffic—traffic, that is, that comes from platforms, apps, and other outside sources— to news sites. Together with the fact that Facebook referral traffic is on the wane, this means that Google’s search algorithm is now perhaps the most powerful mediator of online attention to news.

But for all the influence Google has in directing attention, we know painfully little about how its algorithm selects and curates news. Which sites does it direct traffic toward? And how does Google’s news curation impact the diversity of information found?

To find out, the Computational Journalism Lab at Northwestern, including Daniel Trielli and I, undertook an audit study of the “Top Stories” box on Google search. Top Stories often shows up in the prime real-estate at the top of search results, presenting a carousel of news articles relevant to the query.

To audit Top Stories, we scraped Google results for more than 200 queries related to news events in November, 2017. We selected the queries to test by looking at Google Trends every day and manually choosing terms related to hard news events. These included names of people in the news such as “colin kaepernick,” breaking news events such as “earthquake,” and issue-specific queries such as “tax reform” or “healthcare gov.” We set up our scraper to minimize the potential for result personalization (the process by which Google tailors its search results to an account or IP address based on past use), and ran each query once per minute for a full 24 hours.

In total, we collected 6,302 unique links to news articles shown in the Top Stories box. For each of those links we count an article impression each time one of those links appears.

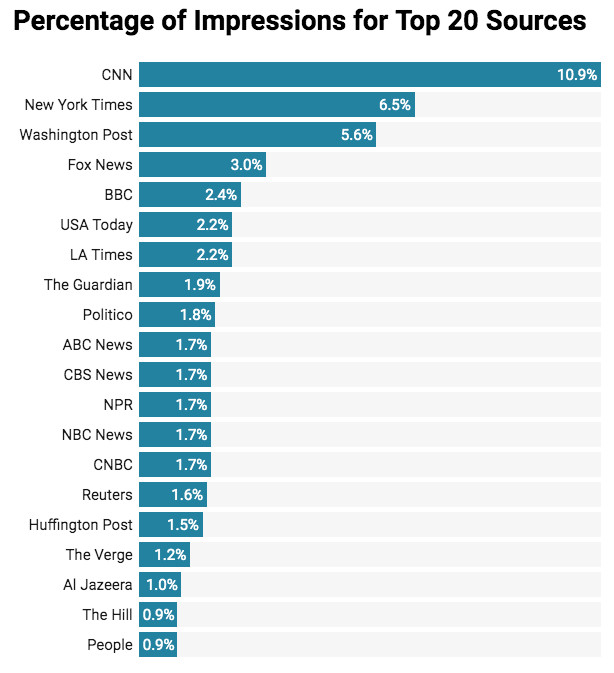

The data shows that just 20 news sources account for more than half of article impressions. The top 20 percent of sources (136 of 678) accounted for 86 percent of article impressions. And the top three accounted for 23 percent: CNN, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. These statistics underscore the degree of concentration of attention to a relatively narrow slice of news sources.

Of course, the concentration of sources also varies depending on the query. On average there were 19 sources per query, but 30 percent of queries had 10 or fewer sources. And sometimes, even if there were more sources, most of the impressions could go to just a handful. For instance, the query “rex tillerson” had 38 sources, but just two of those sources—the Times and CNN—were responsible for 75 percent of the article impressions.

Prior research has shown that search engines can affect users’ attitudes, shape opinions, alter perceptions and reinforce stereotypes, as well as affect how voters come to be informed during elections. As such, media diversity is an important aspect to the way that Google—or any news aggregator—curates sources and perspectives.

To get at this issue in our audit, we looked at the diversity of sources surfaced in Google Top Stories in terms of their ideological lean. More specifically, we used ratings data published in an earlier study which identifies the ideological alignment of the top 500 most-shared news sites on Facebook. The ratings don’t measure the slant of the media outlet per se, but rather reflect the self-reported political affiliation of Facebook users sharing content from those sources. The criteria were published in the peer-reviewed journal Science in June, 2015 by Eytan Bakshy, Solomon Messing, and Lada Adamic from Facebook’s Core Data Science team.

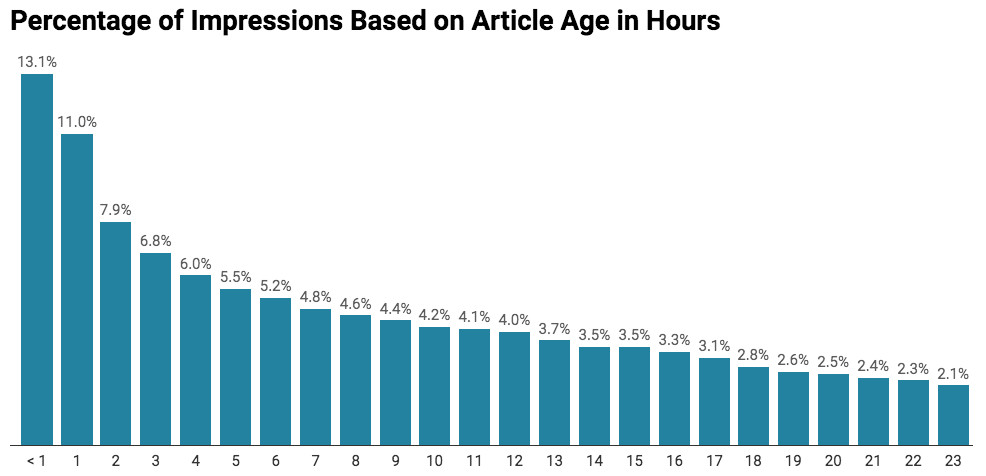

Organizations that can generate fresh copy may be more apt to have that material selected by the curation algorithm.

Our data shows that 62.4 percent of article impressions were from sources rated by that research as left-leaning, whereas 11.3 percent were from sources rated as right-leaning. 26.3 percent of impressions were from news sources that didn’t have ratings. But even if that last set of unknown impressions happened to be right-leaning, the trend would still be clear: A higher proportion of left-leaning sources appear in Top Stories. (Again, this means news sources shared on Facebook more often by people with a left-leaning political affiliation.)

Is there simply more news produced on the left? It appears so. We confirmed this by searching the GDELT database of news articles for the same queries we used to audit Google. In GDELT there were 2.2 times as many articles from left-leaning sources as right-leaning sources. But in Google Top Stories that ratio was 3.2, indicating that the curation algorithm was slightly magnifying the left-leaning skew in comparison to the GDELT baseline.

Another aspect of Google’s news curation is the timeliness of articles selected. Just how quickly does Google churn through news content? Since the Top Stories box provides the approximate age of each article (e.g. “2 hours ago”), we were able to tabulate the recency of articles. What we found is that 83.5 percent of articles were less than 24 hours old and 13.1 percent were less than an hour old. What this means is that organizations that can generate fresh copy may be more apt to have that material selected by the curation algorithm.

In the last part of our analysis, we looked at how much traffic an appearance in Top Stories actually generates. To do this, we combined our scraped data with referral data provided by Chartbeat. Across queries, there is a lot of variation in the number of people searching who could therefore be referred. As an example, in our data, “Matt Lauer” generated 3,961 referrals for each article impression we observed, far more than the average. But a majority of search terms (58 percent) averaged less than 100 referrals per impression.

In order to account for the variability between terms, we built a statistical model that predicts an article’s referrals from Google based on how many impressions it has in the Top Stories Box or in organic search results. The model predicts that an article receiving 60 impressions in the middle position of Top Stories over the course of an hour (we measure one impression each minute) would lead to a 15.5 percent lift in referrals. That’s a boost of almost 1/6 more referrals for an article. And that’s if it’s visible for just an hour.

Impressions generated organically by Google’s search algorithm, rather than in the Top Stories box, accounted for slightly fewer referrals. Sixty organic impressions in an hour would boost referrals by 9.4 percent. Keep in mind, though, that an article could be visible in Top Stories or in organic results for many different queries. Our model offers a lower bound on what the actual boost may be.

Based on the proportion of impressions in our data, and using our predictive model, a very rough estimate would be that CNN received a 24 percent increase in referral traffic from Google from its article’s placements in Top Stories. NPR, on the other hand, perhaps got an increase of about 3.7 percent.

As much as our results help better describe Google’s curation of news, what our study decidedly cannot say is why some sources dominate on Google. Perhaps some outlets have cracked the SEO code for Top Stories. Or there may be a number of other factors taken into account by Google’s algorithm that end up prioritizing certain outlets over others. We just don’t know unless Google is more transparent with the editorial design and goals of news curation in the Top Stories box.

What we do know is that Google’s algorithmic curation of news in search converts to real and substantial amounts of user attention and traffic. News source concentration on Google implies an unequal capture of attention and its benefits, including any advertising or potential subscription revenue that might result. If they are serious about supporting digital-first newsrooms, algorithmic news curators, including Google and others, might be more explicit in articulating the inherent design tradeoffs between the relevance desirable for individuals, the diversity desirable for society or democracy, and the fair competition desirable for news organizations.

Nicholas Diakopoulos is an assistant professor at Northwestern University School of Communication, author of the forthcoming book "Automating the News: How Algorithms are Rewriting the Media" on automation and algorithms in news media, and regular contributor to CJR on these topics.

Has America ever needed a media watchdog more than now? Help by joining CJR today.

Spread the word