Fifty years ago this fall, a campus upsurge turned opposition to the Vietnam War into a genuine mass movement.

On October 15, 1969, several million students, along with community-based activists, participated in anti-war events under the banner of the “Vietnam Moratorium.” A month later, 500,000 people came to a Washington, D.C. demonstration of then-unprecedented size, organized by the “New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.”

As we approach the 50th anniversary of both the Moratorium and Mobilization, it’s worth recalling one critical anti-war constituency whose role was less visible then and remains little acknowledged today.

While student demonstrators and draft resisters drew more mass media attention at the time, many military draftees, reservists and recently returned veterans also protested the Vietnam war—with equal fervor and often greater impact.

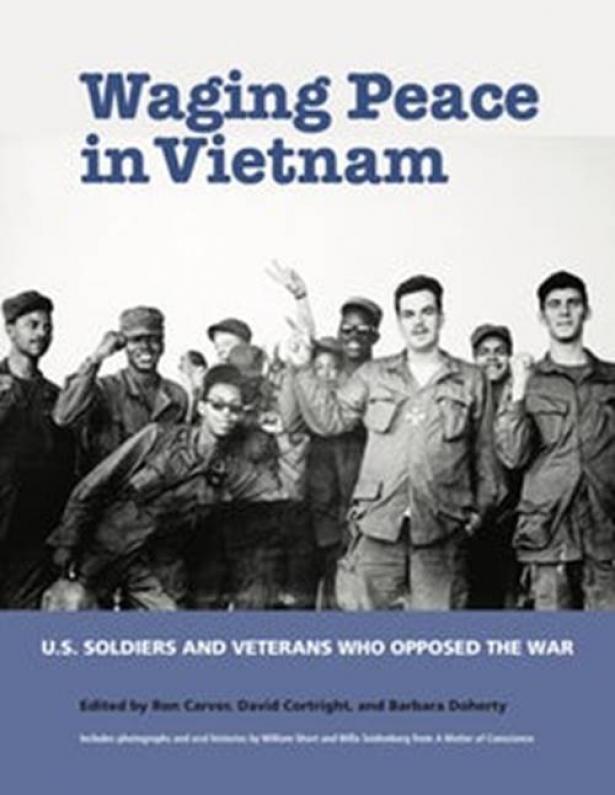

Fortunately, three Vietnam-era activists have just published Waging Peace in Vietnam (New Village Press, 2019), which gives long overdue credit to anti-war organizing by men and women in uniform, and their civilian allies and funders.

Labor organizer Ron Carver, Notre Dame professor David Cortright, and writer/editor Barbara Doherty have crafted a beautifully-illustrated 240-page tribute to the GI anti-war movement. Waging Peace includes fifty first-person accounts by grassroots builders of that movement, plus photo documentation of their work by William Short, a Vietnam combat veteran.

As Cortright notes in the book’s introduction, social science researchers hired by the military (and later academic experts) concluded that one-quarter of all “low-ranking service members participated in Vietnam-era antiwar activity.”

This percentage is “roughly equivalent to the proportion of activists among students at the peak of the anti-war movement.” In the rural and conservative communities which surround most military bases, then and now, “the proportion of anti-war activists among soldiers was actually higher than in the local youth population.”

The Anti-Warriors Today

Now in their late 60s and 70s, many anti-warriors profiled in Waging Peace are long-distance runners in the field. Some remain active in Veterans for Peace (VFP), which held its national convention last weekend in Spokane. One highlight of that annual gathering was the unveiling of archival material and photos which appear in Waging Peace.

This hotel ballroom exhibit included many striking examples of underground press work–mimeographed newspapers for GIs with names like Last Harass, Up Against the Bulkhead, Attitude Check, or Fun, Travel and Adventure (whose acronymic double message was “Fuck the Army!”

Among those viewing younger portraits of themselves in Spokane—along with documentation of their own anti-war activity –were ex-Marine Paul Cox, Army veteran Skip Delano, and former Navy nurse Susan Schnall. In Waging Peace, each one shares a memorable tale of personal transformation, due to their war-time experiences at home or abroad.

A native of Oklahoma, Cox served as a platoon leader in Vietnam’s Quang Nam Province in 1969. There, he witnessed a massacre of civilians, “smaller scale but no less barbaric” than the mass killings at My Lai which occurred a year earlier.

After completing his combat tour, Cox was assigned to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. He and several Maine buddies decided it was “our duty to put out a newspaper and print the truth about Nam.”

Over a two-year period, they and later recruits produced thousands of copies of a clandestine publication called RAGE. As Cox says today, “RAGE was definitely not an example of great journalism.” But it did allow him to redirect his own anger and disillusionment into an effort “to warn others who were about to be deployed.”

In Vietnam, Skip Delano was assigned to a chemical unit attached to the 101st Airborne Division. After his return to Fort McClellan in Alabama, he believed he had earned the right “to comment on the war to other people”—an opinion not shared by his base commander.

Delano helped write and edit a GI newsletter called Left Face, whose distributors faced six-months in the stockade if they were caught with bulk copies. In October of 1969 he and 30 others bravely signed a petition supporting the Mobilization scheduled for the following month in Washington, DC. This deep South expression of solidarity with civilian protestors up north triggered Military Intelligence investigations and interrogations, loss of security clearances, and threats of further discipline.

Protesting in Uniform

A year before Delano’s dissent, Susan Schnall’s dramatic acts of Bay Area resistance drew heavy military discipline. She was court-martialed, sentenced to six months of hard labor, and dismissed from the Navy for “conduct unbecoming an officer.”

Schnall grew up in a Gold Star family; her father, who she never knew, was a Marine killed in Guam during World War II. As a Navy nurse in 1967, she toiled among “night time screams of pain and fear” that came from patients badly wounded and recently returned from Vietnam.

In October, 1968, Schnall became involved in a planned “GI and Veterans March for Peace” in San Francisco. To publicize that event, she and a pilot friend rented a single engine plane, filled it with thousands of leaflets, and dropped them over local military facilities like the Presidio, Treasure Island, the Alameda Naval Station, and her own workplace, Oak Knoll hospital in Oakland.

Then, in full dress uniform, she joined 500 other active duty service people, in a march from Market St in San Francisco to its Civic Center, where they were cheered by thousands of civilian protestors.

Fifty years after Cox, Delano and Schnall rallied their uniformed comrades against the Vietnam war, all three are still engaged in causes like defending veterans’ healthcare against privatization by the Trump Administration (See https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/06/07/under-guise-of-choice-trump-launches-assault-on-veterans-care/)

Later this fall, they and other VFP members are helping to bring the Waging Peace exhibit to Amherst and New Bedford, Mass, New York City and Washington, DC. Next Spring, this book-based display will reach campus or community audiences in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. (For schedule details, see https://wagingpeaceinvietnam.com/exhibit)

Red State Resistance

Activists today, particularly those involved in working class organizing, should buy this book or see the exhibit based on it. Local-level leaders of the GI movement displayed courage, creativity, and audacity when rallying their own “fellow workers” who had been conscripted by the hundreds of thousands.

Much rank-and-file education and agitation about Vietnam occurred on or near heavily guarded military bases located in what are now called “red states.” They became unexpected incubators for homegrown (and imported) radicalism,

Some forms of GI resistance, referenced in the book, involved sabotage of equipment, small and larger scale mutinies, rioting in military stockades, and deadly assaults on unpopular officers (the grenade-assisted retribution known as “fragging.”)

The national network of GI coffee houses described in Waging Peace became places where active duty military personnel could relax, socialize, listen to music, read what they wanted, and have fun with each other and their civilian supporters. This helped break down the military vs civil society divide that is far wider today–due, in part, to the post-Vietnam creation of a “professional army” to replace the rebellious conscripts of fifty years ago.

Thanks to their low morale—and heroic Vietnamese resistance to foreign aggression—U.S. ground forces were no longer “an effective fighting force by 1970,” according to Cortright. “To save the Army,” he says,” it became necessary to withdraw troops and end the war. Their dissent and defiance played a decisive role in limiting the ability of the U.S. to continue the war…”

In an era of “forever wars,” it may be hard to imagine such impactful organizing among active duty military personnel or newly-minted veterans. Let’s hope that the many examples of grassroots activism in Waging Peace prove inspirational and instructive for younger progressives today.

This valuable book might even stimulate some new thinking about how the left can better relate to the 22 million Americans who have served in the military or continue to do so–to their own detriment and that of people throughout the world.

Steve Early was a campus-based recruiter for both the October Moratorium and November Mobilization in 1969. He later served as a full-time anti-war organizer for the American Friends Service Committee in New England. He is collaborating on a book about veterans’ affairs and can be reached at Lsupport@aol.com

Spread the word