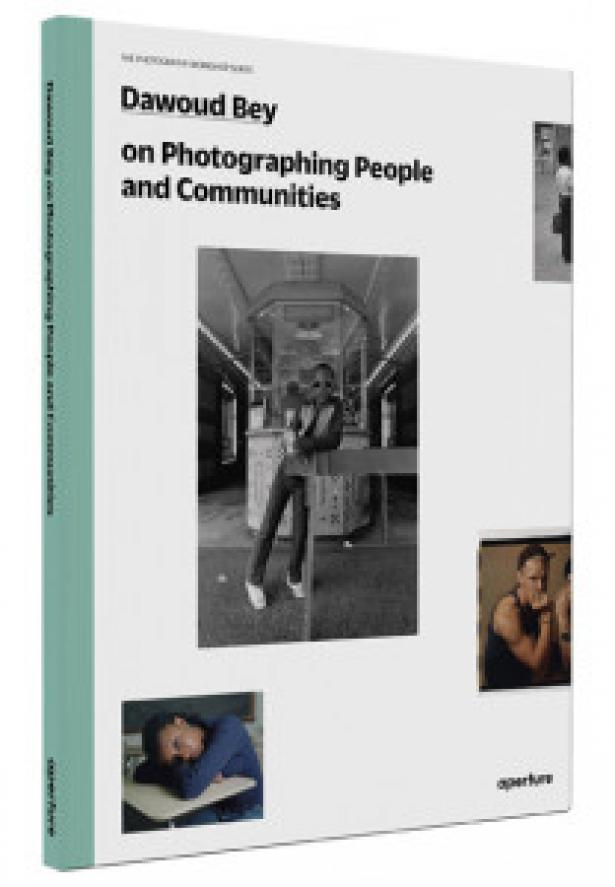

Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities

The Photography Workshop Series

Photographs and text by Dawoud Bey

Introduction by Brian Ulrich

Aperture

ISBN: 978-1-59711-337-3

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.

Dawoud Bey opens his new book, Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities, with a section entitled “People in Front of the Camera”. The narrative front to back is, in essence, as simple as this title and opening section would suggest. Over the course of his 40-year career, Dawoud has taken portraiture and never, seemingly, dressed it in much more than that. “My ideas have largely centered on the human subject; I’m interested in visualizing the human community in a broad range of contexts,” he writes. “The strategy and context may change, but it’s always a person or people sitting or standing in front of the camera. Pictures of people in front of a camera—that describes everything that I’ve done for forty years, every single picture.”

As a teenager Dawoud discovered the work of Richard Avedon via the back page of the The New York Times. He travelled into Manhattan alone -- “There was no one in my neighborhood I could ask: ‘Hey Tyrone, want to go to 57th Street and check out Richard Avedon?’” -- to see his photography at the Marlborough Gallery. “Once I got there, I was blown away by Avedon’s portraits,” he writes. “It was clear from seeing his photographs that the surface contains rich information and could provoke a strong response. I was struck by how the portraits convey a credible sense of identity as the person is isolated in the blank, white background. To me, this is what makes a photograph of a person, a portrait.”

Perhaps his greatest power as an artist lies here. In his ability to make work that changes the world without straying from complete normality. The photographer Brian Ulrich, a student of Dawoud’s at Columbia College in Chicago, details in the book’s introduction the kind of teacher Dawoud was to him and his peers and surmises the secret to his long, fruitful career: “he made us aware of the obstacles ahead of our work in a way that helped us to see and respond to the difficulties of contributing something new in a medium long trafficked by others before us”.

Spread the word