Last week, a flurry of widely shared articles noted that a number of countries deemed to be doing well in the fight against the novel coronavirus have something in common: they are led by women. Whether this observation is meaningful is hard to say; the countries in question are disproportionately small, wealthy, Scandinavian, and, not incidentally, providers of universal health care. But the idea had social-media appeal: could female leaders be, as the Guardian put it, the world’s “secret weapon”? And, if so, why? Speculation ranged from the sociological (women have to be more competent in order to gain power) to the dubiously gendered (they are good at “love”). And there was some wistfulness: what if, at this juncture, there were a woman in the White House, and Donald Trump were ordering takeout while socially distancing in Trump Tower?

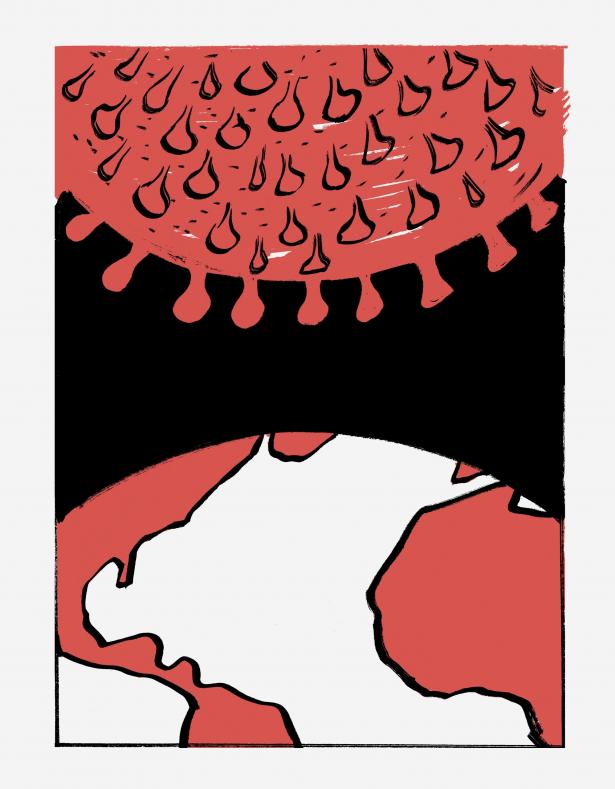

Such notions may be more emotionally satisfying than epidemiologically useful. But they speak to a longing for leadership and for secret weapons—any weapons—against covid-19. As a shared experience, this crisis is unmatched in history. That is why Trump’s decision, last week, to cut off support for the World Health Organization, despite its missteps, is so dismaying. Coupled with his calls, on Friday, to “liberate” certain states under stay-at-home orders, it marks an abandonment of responsibility. (China has not filled the vacuum internationally, in part because of questions about its transparency in managing the pandemic.) So it makes sense that we are frantically scanning the globe, trying to see who might be getting it right.

Some rough answers have emerged from Europe and Asia. Testing is crucial, as South Korea has shown; so is public trust. Social distancing flattens the curve, and, the more testing a nation does, the more options it has for how to maintain that distance, from the blunt tool of lockdowns, which Italy belatedly employed, to the nuanced tracking that South Korea has pioneered. Masks help. At the same time, the pandemic seems to exacerbate national pathologies, from Hungary’s turn from democracy to Egypt’s silencing of critics. Women everywhere are contending with a surge in domestic violence; France and Spain have introduced code words that they can use to seek help.

President Jair Bolsonaro, of Brazil, has decried distancing measures and pushed coronavirus conspiracy theories. (There are plenty of those around the world.) In response, the minister of health, Luiz Mandetta, has played the role of an unbound Anthony Fauci, backing governors who ordered closures in their states. Bolsonaro fired Mandetta last Thursday, but the President is increasingly unpopular; when other political leaders speak out, the bubble of delusion can be burst. Pandemics can have electoral consequences, too: South Korea’s government won a resounding victory last week—and it insured that the turnout was large and safe, with special poll hours for people in quarantine.

The virus is only now beginning to take hold in many developing countries—where masks, ventilators, and even clean water can be desperately scarce—but they are already feeling its economic effects. One is a sudden lack of remittances from nationals working abroad. These account for about a fifth of El Salvador’s G.D.P. and a quarter of Somalia’s. When a waitress or a shopkeeper in Paris or Queens loses income, money stops going to Senegal or Nepal. Many families in Afghanistan’s Herat Province rely on income from Iran; when Iran’s economy seized up, a hundred and fifty thousand workers crossed back into Herat, some bringing the infection with them. The fate of refugees and migrants is one of the most wrenching questions of the crisis, illustrated in images of evicted African workers sleeping on the streets of Guangzhou, and in accounts of Kenyan workers returning from the Gulf States to face a curfew that has become an engine of police brutality.

India, with a population of more than 1.3 billion, shows how the pandemic can be a source of both unity and dangerous discord. Prime Minister Narendra Modi called for the entire nation to join together in cheering health workers on March 22nd, at 5 p.m.—all India is in one time zone—and it did. Yet the country’s early coverage of the outbreak focussed on clusters in the Muslim community, against whom the B.J.P., Modi’s party, has incited violence. And, when Modi effectively shut down the country, migrant workers had little warning. A stream of people, by many estimates hundreds of thousands of them, began walking, often hundreds of miles, to their home villages. Others remained in cities. Last week, Mumbai had at least two thousand confirmed cases; it is both a financial capital and a metropolis whose slums epidemiologists view with apprehension, compounded there, as elsewhere, by a lack of reliable data. There are similar fears for Lagos, Nigeria, a city of more than twenty million people, which had two hundred and fifty cases by the end of last week. (And, for that matter, for Moscow, where, last week, there were eighteen thousand cases.) Resources matter, but scientists can, as yet, only hazard a guess as to precisely how those countries, and far poorer ones, will experience covid-19. Will the relative youth of their populations provide a buffer? Will high rates of tuberculosis and H.I.V.—a particular factor in South Africa, where cases are rising steadily—make the toll worse?

Alyssa Ayres, of the Council on Foreign Relations, noted that one of the Indian states that has had the most success in fighting covid-19 is Kerala, which is home to about thirty-five million people. Kerala is not governed by the B.J.P. but by a coalition of leftist parties, and has long been distinguished by its well-functioning health system. The state’s health minister, K. K. Shailaja, a woman being called the Coronavirus Slayer, mounted an early and aggressive response. Kerala was also helped by having had, in effect, a rehearsal—in 2018, it managed an outbreak of the Nipah virus, which can attack the brain. There is a parallel story in Bangladesh, which has been able to draw on public-health capacities it has built up, over several decades, to fight cholera. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the former President of Liberia, in a call for concerted action to counter covid-19, invoked the lessons that African countries had learned from the Ebola epidemic. As Ayres put it, “There is deep expertise in places that most Americans aren’t thinking about.”

That may be one of the most important messages from the wider world. The struggle to control the pandemic has to be a joint project, as if the whole planet were seeking to reach the moon together. Every nation can contribute, including those whose voices are less often heard. And no one can be left behind.

Published in the print edition of the April 27, 2020, issue, with the headline “Wide World.”

[Amy Davidson Sorkin has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 2014.]

Spread the word