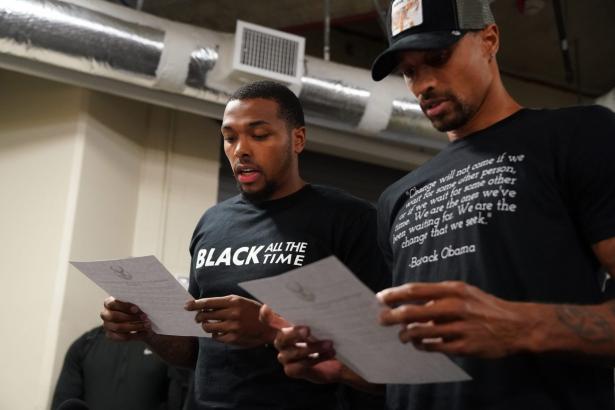

Abdul Malik analyzes the major league sports stoppages from an organizing perspective. Image via.

Players in four major American sports leagues went on a wildcat strike yesterday, with other leagues and sports watching closely.

This strike began in the NBA. Players were responding to what they felt was the league’s inaction around issues of racial justice, including in the wake of the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin on August 23rd. Fred VanVleet of the Toronto Raptors noted in an extraordinary interview that a stoppage of play would put owners’ finances under threat, and force them to leverage their political capital to push authorities to prosecute the police who shot Blake.

His analysis shows these workers understand the power they hold in the workplace. The strike was also the outcome of years of organizing on the shop floor, poor concessions from management, and worker frustration on the job.

Not the first NBA wildcat

Make no mistake: despite the #NBABoycott hashtag, this was a wildcat strike, arguably the most visible one in years.

To understand this wildcat, it’s vital to know about the last one.

1964 was a big year for the NBA. The first ever televised All-Star game was happening, and the flagging league needed it to be a success in order to secure ongoing television contracts.

Meanwhile, negotiations around a pension plan between the Players’ Association and the Board of Governors had broken down, with the Board stalling for months.

Hours before tip-off at the All-Star game, the players took an informal strike vote: 11-9 in favour. They told the owners they wouldn’t play unless they got their pension plan. This was a do-or-die moment for the league, with its lucrative, near-guaranteed TV deal hanging in the balance.

Minutes before the game was supposed to start, the players’ demand was met. It was the first pension plan in the history of professional sports. To this day, it remains the best one.

Covid-19, the bubble, and worker power

56 years after the 1964 wildcat, when the NBA made its plans to restart play after the COVID-19 shutdown, in a “bubble” system at Disneyland, it did so amidst the ongoing protests around police violence in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

In meetings prior to the bubble being codified, mass Zoom calls with players and the union were a forum to voice thoughts openly. Many players in the NBA, a majority black league, understandably expressed discomfort around playing a game for entertainment while there were serious issues of social justice and anti-racism that needed to be addressed.

The majority of them still committed, with key outliers. In the WNBA, league superstar Maya Moore took off the entire season in order to support the case of Jonathan Irons, a black man serving a 50-year sentence for assault and robbery, widely believed to have been wrongly convicted and imprisoned by an all-white jury.

Then Jacob Blake was shot in the back seven times, and two protestors were murdered at the hands of white supremacist militia, with the officers who shot Blake given administrative leave. The Toronto Raptors indicated that they were looking at withholding labor for their first semifinal game against the Boston Celtics, and were in conversation with the Celtics about making it a mutual decision. Raptors head coach Nick Nurse went as far as to say some players were considering leaving the bubble entirely.

A few hours later, the Orlando Magic took the court to play the Milwaukee Bucks, who, without any warning, didn’t show up. They had struck, staying in the locker room and requesting a line to the Wisconsin Attorney General, Josh Kaul. Unlike past actions around racial justice, this was not sanctioned by management.

Immediately, this sparked a domino effect. All games for August 26 and 27 were cancelled. Color commentators walked away from their desks. Referees and coaches both issued statements in support.

Most importantly, three of the other four active major sports leagues in America joined the strike: Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer, and the WNBA. Despite its brevity, this was the most prominent sector-wide wildcat in recent memory.

Steady organizing to get to this point

Miraculously, the August 26 wildcat occurred four years to the day Colin Kaepernick first took a knee during the national anthem at an NFL game, and it should be noted that it took four years of pressure, organizing, and state violence to reach this point.

Watching vlogs and reporting from the NBA bubble is fascinating. There are ongoing conversations about racial justice behind the scenes.

It’s clear many players are uneasy about being insulated from the world while so much is happening. Watching these videos, which are quite earnest, and hearing anecdotes about conversations that weren’t filmed, suggests that players were pushing each other to confront the idea that taking action was more important than playing basketball. Constant conversations and informal one-on-ones as well as a guiding hand from the union provided an excellent opportunity for players to educate, agitate, and organize one other to challenge league management.

Compromises around racial justice fought for and won by the union were considered inadequate by many players: the league would commit to Black Lives Matter messaging throughout the remainder of the season, and players could choose pre-selected messaging around social justice to put on their jerseys. The outrage, while simmering, was present. Players who would have preferred to wear blank jerseys were told they wouldn’t be allowed to play. Despite the league’s efforts to be “woke,” including allowing kneeling for the anthem, putting Black Lives Matter on the court, and vague racial justice messaging, it’s clear that wasn’t enough. Many players continued to express stress and dissonance with what they were doing versus what was happening across America.

It would be foolish to assume that all the players were in complete agreement about what was going on outside the bubble, or the steps that should be taken to address it. There’s already a large diversity of opinions on police violence, police abolition, and police reform.

However, players presented a united front against league management. In the Milwaukee Bucks’ statement to the public about withholding their labor, all players were present. Throughout the bubble games, nearly every player (really, all but a few) kneeled.

Also key, however, were opportunity, pressure, and demand. The NBA was slated to take a staggering loss on the season’s Covid interruption, and the bubble presented a last second, three-point play to recoup economic losses. Every game counts. By instituting a stoppage of play at this moment, with all eyes Kenosha, the players put the ball in the owners’ courts. Without knowing for sure, one suspects Bucks ownership is trying desperately to reach the governor’s office.

Things may have been different if the NBA had allowed players to express themselves the way they wanted. For now, it’s scrambling to figure out what’s going on, blindsided by a wildcat and lagging a step behind worker action.

The multi-sector nature of the strike is also the outcome of a well-seized opportunity. Three other major leagues stopped play the same day. The two larger of them have nothing close to the political culture of the NBA, a league dominated by black athletes who have historically been told to “shut up and dribble.” The NBA is also smaller in terms of revenue than the MLB, but the MLB fell in line. A successful strike is not just a numbers game, it’s also based on who is best to lead in the moment. The MLS and WNBA could not have done this on their own and made an impact, but their presence is obviously deeply felt as they withheld their labor in solidarity.

It’s worth reasserting the timeline: four years. Good organizing, a good strike, and most importantly, a good outcome, is a confluence of time, effort, and opportunity. The time part is largely where organizing falters. You can’t rush good organizing, and no grueling hour spent organizing is ever wasted.

A single aggrieved worker, four years ago, eventually led to an environment in which players can organize a total shutdown of three of North America’s five largest sports leagues (plus one of the smaller ones).

What now?

The collective bargaining agreement between the NBA and the Players’ Association explicitly forbids strikes, and labor relations after 1964 have instead been marked by several lockouts, the most notable of which was considered a major loss for the union.

When the Milwaukee Bucks players walked, they were in flagrant breach of their CBA. But they’re protected because it was a cohesive effort — they can’t all be fired — and because the optics around workers being punished for reasons of justice would be disastrous for NBA management.

This upends the relationship between athletes and owners in significant ways, with the players flexing power outside the boundaries of their union, their CBA, and their own upper management.

At one point, the superstar LA Clippers and LA Lakers voted to boycott the season, which had the potential to cancel the entire remainder of play. Those two teams, led by LeBron James and Kawhi Leonard, perhaps the two most dominant players currently in the sport, are at a revenue and audience level all their own.

Following a meeting of the NBA board of governors this morning, there are some rumors that players have chosen to resume play, although that remains unclear. The details of what concessions owners are offering are not yet public, but likely will be soon.

It’s easy to point to this and indicate the degree of privilege these players hold. They are some of the most well-compensated in pro sports (due in no small part to their extraordinarily powerful union), but comparing player salaries to owner revenue largely shows a scaled-up version of a typical worker-manager pay imbalance.

It’s still a management-worker paradigm, and the fundamentals of what led to this moment — a problem, management’s inability to address this problem, difficult conversations on the shop floor, and a flashpoint that led to a total work stoppage — are repeatable in every workplace. In every sector.

Abdul Malik is a writer and IWW member based out of Edmonton, Alberta. His work has been published in the Progress Report, Passage, Briarpatch, and Alberta Politics.

Organizing Work produces original reporting about organizing campaigns, from the perspective of the workers involved, and debates union strategy.

SUPPORT ORGANIZING WORK VIA PATREON

Spread the word