Audre Lorde said in 1982 that “there is no such thing as a single issue struggle because we do not live single issue lives.” This quote is often used on t-shirts and posters, but divorced from the context in which she gave that speech at Harvard University during a commemoration of the life of Malcolm X. And the context can be neatly summed up as this: her lessons from the 1960s illuminate why we cannot afford to reduce our history to fairy tales that inform our present.

In that very same speech, Lorde chastened us that “we know what it is to be lied to, and we know how important it is not to lie to ourselves.”

The lives of Black folk have always been a “both/and” rather than an “either/or.” Nothing about the complexity of Black life can be drilled down to one origin or root, because of the multiplicities of our lives. By virtue of being designated as Black in a white supremacist society, we are always othered in relationship to the dominant culture. As such, Blackness, though socially constructed, introduces a unique lens through which we experience the world, and that unique lens interacts with each other socially constructed category in specific ways.

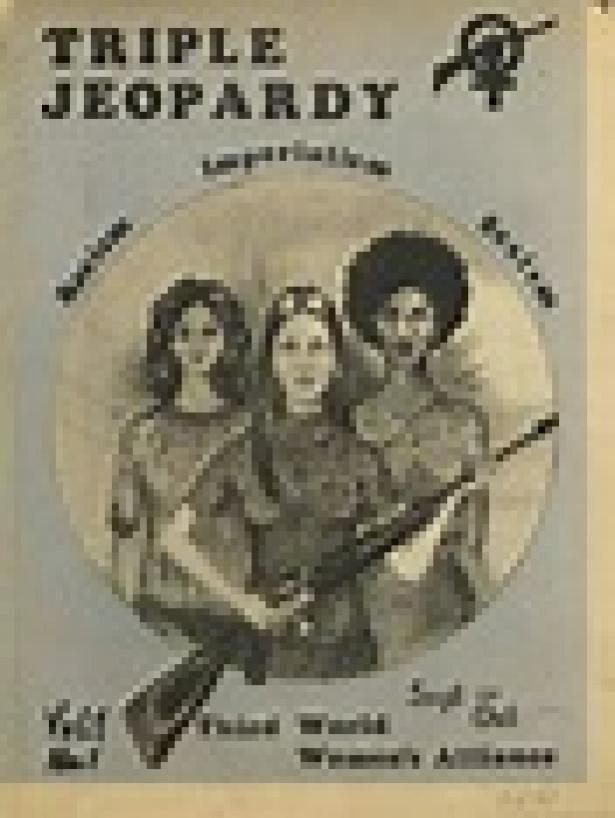

The lie here that Linda Burnham refers to in The Activist Roots of Black Feminist Theory is one in which we locate the lived experience of “intersectionality” or “multiplicities” in the academy rather than in activism, particularly that advanced by the women in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Combahee River Collective, and the Third World Women’s Alliance. Though scholars rooted in the academy do invaluable work to help us better understand the world around us and our role within it, Burnham argues that solely locating this worldview in the academy not only obscures the contributions of feminist activists and organizers, but it discredits the role of activists in the development of that worldview through their lived experiences.

Burnham is absolutely correct that there are many forms of knowledge production, and that knowledge production from the academy should not be privileged over the knowledge production derived from lived experience. Additionally, there were women rooted in both the academy and activism – like Barbara Smith and Demita Frazier – who saw their academic work as a part of their activist work, interrupting and intervening in the notion that only knowledge produced by white people was valid theoretical ground. This both/and perspective relays the fullness of the contributions of Black women to Black feminist thought and action.

OUR LEARNING COMES THROUGH TRANSFORMATION

Lorde said that “we do not have to romanticize our past in order to be aware of how it seeds our present. We do not have to suffer the waste of an amnesia that robs us of the lessons of the past rather than permit us to read them with pride as well as deep understanding.” The truth of Burnham’s argument that we do not have to attribute our learning, learning that comes through personal and social transformation, to the contributions of a few brilliant individuals hits home – it is a familiar pattern that exists through movements, on many levels and on many occasions. Some may be frustrated at Burnham’s insistence that intersectionality has its roots in more places than the academy, and perhaps even dismayed at the assertion that sexism (alongside homophobia and class hierarchy) was alive and well in the movements that fought to change our material and social arrangements, but these assertions are the both/and’s of all movements – that at the same time that we fight for liberation, there are times when that liberation is rendered incomplete by an unwillingness to free ourselves from the very structures that we claim to abhor.

Lorde asked, “Can anyone of us here still afford to believe that efforts to reclaim the future can be private or individual? Can anyone here still afford to believe that the pursuit of liberation can be the sole or particular province of any one particular race, or sex, or age, or religion, or sexuality, or class?” The answer of course, is no – but that doesn’t seem to stop people from believing that they can try. Intersectionality continues to be sharpened by those who continue to be left out and left behind from the liberation projects that claim to include us. And as Burnham asserts, those who enter in this moment of the movement are fighting for themselves at the same time that they fight for their families, communities, and loved ones.

It is still far too common to hear disgruntled voices bemoan the ways in which they claim “intersectionality has hijacked the movement.” But what they really mean is that they only want to prioritize liberation for some, and not for all. They mean to say that anything that does not prioritize the needs of heterosexual, cisgender, able bodied, class flexible, citizened, male-identified people cannot be considered unless and until their needs are addressed. Far from harsh or dramatic, it is to say that intersectionality is a way of making more complex what it means to achieve freedom – and that requires work, a change of ingrained practices, habits, and ways of being that uphold the status quo. There are still too many in our movements who are fine with the status quo as long as it includes them – and this, itself, is not a transformative practice but instead a reproductive one, reproducing the same dynamics with different people enjoying access to corrosive power.

Lorde says, “It is easier to vent fury upon each other than upon our enemies.” Profound and yet quite simple, these assertions make transparent our task as it relates to being dangerous together rather than being dangerous for each other. To position intersectionality, or the complexity of our lives that demand attention, as “outside” or “extraneous” demonstrates a lack of depth with which we attack the problems at hand. We cannot afford to abandon one another in pursuit of a power that was deliberately designed to keep all of us from it. In order to access the power we need to change our lives, we must work to dismantle power as domination and instead, advance power through interdependence, relationship and cooperation.

Alicia Garza is the principal of the Black Futures Lab and the co-creator of #BlackLivesMatter and the Black Lives Matter Global Network. She’s the author of The Purpose of Power: How We Come Together When Things Fall Apart (One World/Penguin Random House, 2020) and shares her thoughts on politics and pop culture in a weekly podcast, “Lady Don’t Take No.”

Please also read the Linda Burnham article also reprinted by Portside today.

Spread the word