Jesus ‘Chuy’ Negrete, Chicago folklorist, writer, singer of Chicano movement, dead at 72

Jesus “Chuy” Negrete composed hundreds of corridos — Mexican folk ballads.

“Some people used to say he was the Mexican Bob Dylan,” said U.S. Rep. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, D-Ill., for whom he once wrote a corrido urging people to vote for him for mayor of Chicago.

Others “called him the Chicano Woody Guthrie,” said actor Edward James Olmos, a friend who said Mr. Negrete “was like a brother” to him.

“His ability to make you laugh and make you cry was superb,” Olmos said. “He told our stories.”

Mr. Negrete, 72, died May 27 of congestive heart failure at Glenbrook Hospital in Glenview, according to his wife Rita Rousseau.

He would write his ballads for any occasion. He composed one in 1983 for the funeral of slain Chicago activist Rudy Lozano.

“Your death has not been in vain,” he sang. “The ideas you left are in my hands. . . . Your people continue with you.”

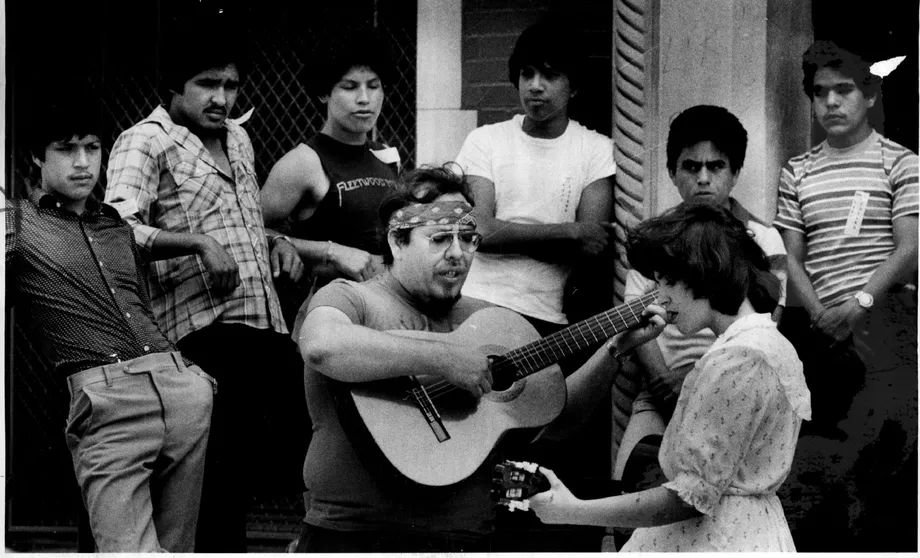

Jesus Negrete and Teresita Delatorre led songs as mourners gathered at Farragut High School in 1983 to honor slain activist Rudy Lozano. Al Seib / Archivo Sun-Times

Another, ”La Tragedia de Tucson” told the story of the 2011 mass shooting in Arizona in which six people were killed and more wounded, including former U.S. Rep. Gabby Giffords.

A folklorist and folksinger, the Rogers Park resident was a teacher and administrator at Chicago–area schools. But he traveled widely, using his guitar and harmonica to share stories of Mexican history.

“He was an educator of the highest extreme,” Olmos said. “He would go to prisons. He would go to schools. He would go to universities.”

In 1988, Mr. Negrete sang at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Hispanic Heritage Week celebration.

He’d often perform for prospective students at the University of Houston. After listening to his stories and songs of pride and resilience, many enrolled, said Lorenzo Cano, retired associate director of the school’s Center for Mexican American Studies.

“That kind of sewed it up for a lot of students,” Cano said.

In 1993, the Tucson Citizen described college audiences cheering as Mr. Negrete shouted: “You are Olmeca, Tolteca, Azteca, Chichimeca! You are Mestizo!”

He told students there that, in pre-Columbian days, “We were architects, engineers, mathematicians, botanists, surgeons, philosophers. Yeah, we had a lot going for us, not just frijoles and tortillas.”

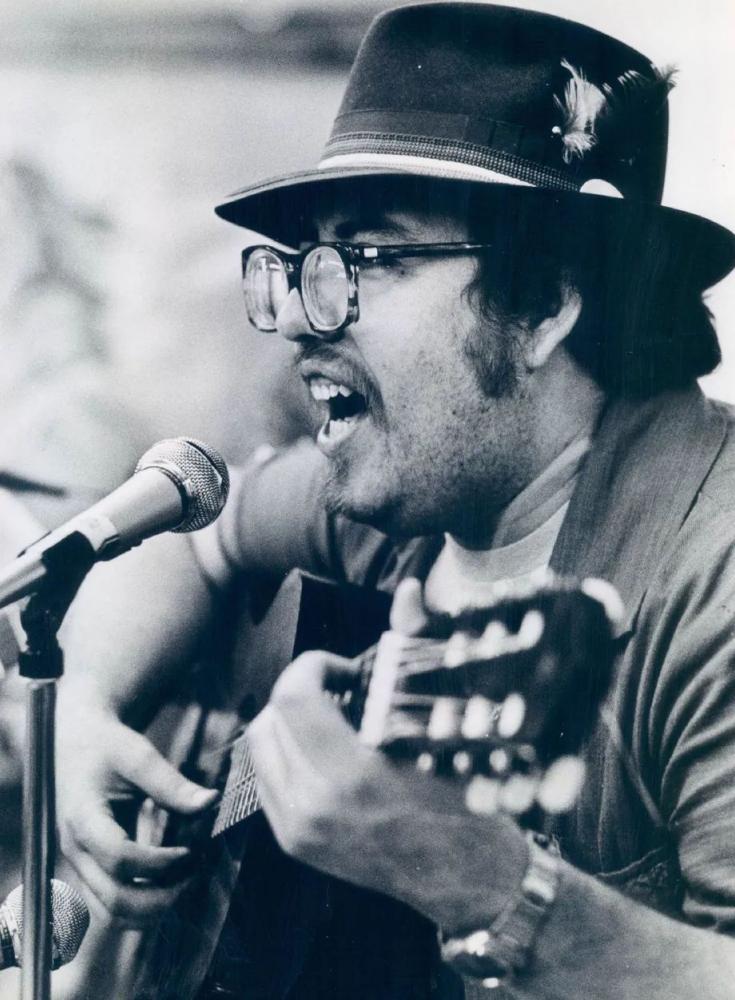

Jesus “Chuy” Negrete performing. Barry Jarvinen / Archivos Sun-Times

“He sang these corridos he wrote, walking you through 500 years of history,” said Sarah Zenaida Gould, interim executive director of the Mexican American Civil Rights Institute in San Antonio. “It was a story of colonial power, a story of oppression, but also a story of resistance and resilience. I suspect his performances were part of many Mexican American university students’ political awakening.

“He was actually the very first person to explain my middle name to me,” Gould said of the name that’s been handed down for generations. “In Mexico, ‘Zenaida’ is part of a resistance corrido associated with the Mexican Revolution.”

“He sang these corridos he wrote, walking you through 500 years of history,” said Sarah Zenaida Gould, interim executive director of the Mexican American Civil Rights Institute in San Antonio. “It was a story of colonial power, a story of oppression, but also a story of resistance and resilience. I suspect his performances were part of many Mexican American university students’ political awakening.

“He was actually the very first person to explain my middle name to me,” Gould said of the name that’s been handed down for generations. “In Mexico, ‘Zenaida’ is part of a resistance corrido associated with the Mexican Revolution.”

“Chuy Negrete introduced thousands of people to the history and the experience of Chicanos in the U.S. through his innovative delivery of corrido ballads and bilingual storytelling, which were at once humorous and deeply critical of our society,” said Juan Díes, co-founder of the Sones de Mexico ensemble. “Chuy’s legacy will be reaching scores of young Latinos who felt lost in American society.”

Garcia said he met the folksinger in 1974 while attending what’s now called the University of Illinois at Chicago. Mr. Negrete worked at the Rafael Cintron Ortiz Latino Cultural Center there and “always had his guitar in his office and his ranchero hat,” the congressman said.

People often asked him to compose corridos about their loved ones for funerals. He wrote and performed the elegies for free.

Mr. Negrete’s more lighthearted ballads might name-dropped a local personality or describe “a love story or an elder lecturing you about your bad Spanish,” Garcia said. “He was masterful at the Spanglish idiom, and he would always make people laugh.”

Mr. Negrete was born in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, the only boy of five children of Melesia and Bernardo Negrete. When he was a year old, the Negretes undertook a perilous crossing of the Rio Grande into the United States.

His mother “told us they got in a little boat with us kids, and she was worried the boat would tip over,” he once told the Chicago Tribune.

His parents toiled as migrant workers, his wife said, before his father landed a job at Republic Steel. They settled in South Chicago.

Young Chuy graduated from Chicago Vocational High School and got a bachelor’s degree in education at UIC and a master’s in education from Chicago State University. He was a bilingual teacher for the Chicago Public Schools and a teaching assistant at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. He worked in Chicano studies at Malcolm X College. He also taught as an adjunct faculty member at what was then Robert Morris College, Roosevelt University, Indiana University Northwest in Gary and the University of California, Berkeley, according to his wife.

His music was influenced by the civil rights movement and by California’s El Teatro Campesino, which started with farm workers performing street skits to dramatize their struggles. Later, Luis Valdez, the theater’s artistic director, created “Zoot Suit,” a stage sensation that incorporated Mexican American history and indigeneous symbolism. Olmos’ career took flight after he starred in the play.

In the 1970s Mr. Negrete helped found Teatro del Barrio, often performing in the street theater troupe with three of his sisters. Its musical presentations included one on the women of the Mexican Revolution and another about Cesar Chavez, the labor leader who fought for better conditions for farm workers.

They performed at culture festivals, including one staged at the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon near Mexico City, according to his sister Rosa Negrete Livieri.

His work on the road led to his friendship with Olmos.

Later, Mr. Negrete performed with Livieri and others in the group Flor y Canto — Flower and Song.

In 1988, he met his future wife at the National Museum of Mexican Art. He was moving from exhibit to exhibit, singing.

“He caught my eye, and I followed him,” she said. “And I caught his eye, and he said, ‘Stick around.’ ”

Both were in their 40s and had never married.

“We were thrilled to find each other,” Rousseau said.

In addition to his wife and his sister Rosa, Mr. Negrete is survived by his sons Joaquin and Lucas Negrete-Rousseau and sisters Martha N. Bustos, Juanita Negrete-Phillips and Santa Negrete-Perez.

A memorial service is being planned for the fall at the National Museum of Mexican Art.

“He could wind you up, are you kidding me?” Olmos said. “Tell you stories about the revolution and the difficulties of what had been done to the people, our ancestors, our culture, his guitar never stopping. He was a real troubadour.”

Maureen O'Donnell is a Staff Reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times

Spread the word