In a time of high inflation, you hear a lot about companies “passing costs” on to customers. In order for companies to maintain their God-given right to earn a profit, they must raise prices to offset the cost of producing goods and getting them into peoples’ hands. And thanks mostly to the hidden risk, exposed by the pandemic, of neoliberal gospels like just-in-time logistics, deregulation, and offshoring, prices really are going up.

But there’s something else mixed in with this latest bout of inflation. Companies aren’t just passing costs onto us. With corporations using inflation as a cover for raising their prices, you and I are passing profits onto companies.

“Executives are seizing a once in a generation opportunity to raise prices,” reads a Wall Street Journal storyexplaining that around two-thirds of the largest publicly traded companies are showing profit margins higher today than they did in 2019, before the pandemic. Over 100 companies show profit margins of 50 percent or more above those 2019 levels.

In other words, inflation is being enhanced by exploitation. Profiteers are using the frenzy around higher prices as an excuse to reel in much more than increased costs. President Biden has only tiptoed around calling this out and taking action. But telling a story about corporate price-gouging and sustaining a push against it is a key component to resolving the crisis—and, perhaps, reversing Biden’s slump.

Corporate executives are not hiding their handiwork; instead, they’re boasting about it in financial disclosures and earnings calls. “We have not seen any material reaction from consumers,” said the chief financial officer of Procter & Gamble, the world’s largest consumer goods company, which has hiked prices three times in the past year. “What we are very good at is pricing,” said Colgate-Palmolive’s CEO. “We find that taking several small price increases is more effective than one large price jump,” added the CFO of Unilever. Dollar Tree, a discount store which has the word “dollar” in its name, has decided to permanently set its price point at $1.25, stating specifically that the move is “not a reaction to short-term or transitory market conditions.”

A Biden speech in the manner of JFK, by itself, will do little. But reviving the force of the U.S. government to promote competition and police illegal behavior might help.

There are a ton of sneaky marketing techniques to raise prices on consumers invisibly, like putting goods in “jumbo” packages that actually increase unit costs, or slowly taking away promotions and coupons. The end result is the U.S. consumer getting nickel-and-dimed, paying more for less. Talk of inflation creates those consumers’ expectations of more inflation, which retailers take advantage of to smuggle in their own inflated prices, solely for profit.

The good capitalist will say that as long as the consumer doesn’t object, companies have every right to maximize profits. And anyway, a company that wants to steal market share can always come in and undercut prices.

But that’s not how it works today. While we have the illusion of choice in retail aisles, the bulk of the products we see there are manufactured by a handful of companies. If they raise prices in concert, there’s no competitor with the shelf space or profile to change that dynamic, putting consumers at the mercy of profiteering giants. You don’t need CEOs to get into a smoke-filled room to determine price movements; everyone watches one another and knows when to react. The fact that companies brag about their price hikes on earnings calls makes this coordination all the easier.

It’s worse than this, actually. The “real inflation” across production and distribution systems can also be chalked up to consolidated actors exploiting a crisis. Whether you’re talking about the hedge fund–fueledcontainer ship cartel (whose net profits, as my colleague Bob Kuttner reported yesterday, grew nine times the rate they did a year ago), freight rail cost-cutting, or trucking deregulation, the original sin snarling the supply chain is a profit motive that has actually increased during the crisis. The profiteering is happening at every link of the chain.

Behind all of this are demands from Wall Street investors and analysts, who will explicitly punish companies that don’t step up and gouge their customers. When Target said it would not raise prices after exceeding its profit estimate, its stock sank.

This puts the Biden administration in an unenvious position. There is a real supply-chain bottleneck. Yet the preponderance of the evidence shows that large corporations with pricing power are taking advantage of the situation to siphon cash from their customers’ wallets.

The administration has been thinking about how to present the profiteering argument, and take action. Biden has executed a couple halting steps, like asking the Federal Trade Commission to look into price gouging in the gasoline market. But his pre-Thanksgiving speech on Tuesday was more defensive, highlighting job growth, noting some progress in clearing cargo backlogs (progress that is a bit dubious if you dig into the numbers), and hailing Walmart’s CEO.

On gas prices, Biden was willing to say that “the price of oil has fallen by 10 percent over the last few weeks [but the] price at the pump hasn’t budged a penny,” condemning gas refiners and producers for “paying less and making more … pocketing the difference as profit.”

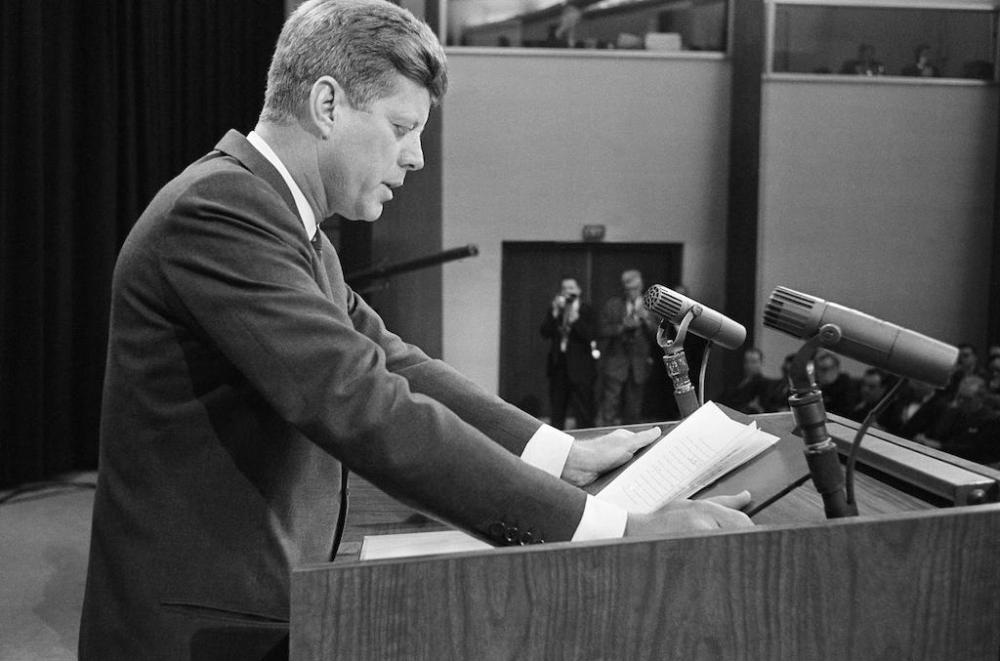

President Kennedy reads a statement on Steel Prices, April 11, 1962 AP PHOTO

There’s a balancing act here, of course, because long-term Biden wants to shift away from gasoline, yet making it cheaper would increase use. Still, the broader point of profiteering under the mask of inflation is broadly applicable. And there’s a blueprint here that shows both the promise and pitfalls of such a campaign.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy wanted to head off an inflation surge. He personally negotiated a deal between steel companies and unions that added worker benefits while holding off on price increases. But the CEO of U.S. Steel told Kennedy that April that he would break the agreement by raising prices by $6 a ton, and all of U.S. Steel’s rivals followed suit.

As quoted by Kennedy historian Arthur Schlesinger, the president reportedly told White House staff, “My father always told me that all businessmen were sons of bitches, but I never believed it until now.” Hardly a populist, JFK gave a prime-time speech carried by all the television networks the next day, laying out the steel industry’s lowering costs and increasing revenues, and saying: “the American people will find it hard, as I do, to accept a situation in which a tiny handful of steel executives whose pursuit of private power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility can show such utter contempt for the interests of 185 million Americans.”

In addition to making the public argument, Kennedy announced an antitrust investigation into the near-simultaneous price fixing. The FBI got involved, discovering that a Bethlehem Steel executive said just days earlier there would be no price increase, only to change their mind later, which was evidence of collusion. The Defense Department shifted procurement to companies that didn’t raise prices. Within four days, all of the steel companies rolled back their prices.

But U.S. Steel was made of, er, stronger stuff. They implemented all the price hikes they wanted over the next 18 months, with no objection from Kennedy. His successors never intervened in corporate decision-making either. Today, corporate America is far stronger than it was 59 years ago.

A Biden speech in the manner of JFK, by itself, will do little. But reviving the force of the U.S. government to promote competition and police illegal behavior might help. In addition to the gas industry investigation at the FTC, on Tuesday the Justice Department sued to block a merger between two of the nation’s largest sugar producers, which would likely hike prices for this ubiquitous food component. The administration has also been active in addressing concentration in the meat processing industry, which during the pandemic has seen increased prices at the grocery store even as farmers get exceedingly low prices for cattle and chickens.

You could readily extend out these kinds of price-fixing investigations; the raw material is broadly available in earnings calls. We also know that big-box retailers are ensuring their own stocks by demanding that suppliers service them first; this type of coercion is illegal under the Robinson-Patman Act, which is still on the books but essentially unenforced. As we learn from Kennedy’s failure to sustain action against the steel industry; eternal vigilance would be needed for a successful end to inflation-fueled profiteering.

Such action can change corporate behavior. An FTC policy statement announcing its intent to enforce against the repair restrictions that electronics and equipment manufacturers put on their products has already led Microsoft and Apple to change their policies and give consumers the right to repair without having to have it done by Microsoft and Apple.

But you can’t just rely on grumpy business reporters and activists to yell about profiteering. You can’t even rely on a president’s words. You have to make it a priority, and use the powers of government to reverse the conditions that broke our supply chains and ceded control to corporate giants.

David Dayen is the Prospect’s executive editor. His work has appeared in The Intercept, The New Republic, HuffPost, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and more. His most recent book is ‘Monopolized: Life in the Age of Corporate Power.’

Fortify your mind! Join the Prospect today

Support The American Prospect's independent, nonprofit journalism by becoming a member today. You will stay engaged with the best and brightest political and public policy reporting and analyses, and help keep this website free from paywalls and open for all to read. Our membership levels offer a range of perks including an opt-in to receive the print magazine by mail.

Spread the word