DETROIT — John Weyer remembers the day that he threw out his United Auto Workers (UAW) shirts.

He started as a member of Local 1264 in 1995, taking a production job at the Sterling Stamping Plant in Sterling Heights, Michigan. For the following two decades, he was a proud union member. Weyer saw the labor movement as a key part of building a better world. But by 2014, he realized that some of the UAW leaders to whom he had long looked up were deeply corrupt, spending members’ dues on extended lavish California vacations and luxury goods.

“Think about how hard one of our nurses in Toledo on the midnight shift has to work for two and a half hours of her time a month to pay union dues,” said Weyer when I asked him why the corruption scandal that has roiled the union in recent years hit him so hard. “She’s cleaning somebody’s diaper, wiping somebody’s ass, and staying on her feet for twelve hours to pay those dues. Or think about the single mother who is working the second shift and can’t see her kids because they’re in school. How hard does she work for her dues? [The union’s leaders] were stealing that money from our members.”

The loss of union pride was so devastating that he briefly saw a therapist to help him grieve. For years, he turned his focus elsewhere, to coaching youth sports. It was only in the lead-up to the most recent international leadership election that he became active in the union again.

The election was the first in the UAW’s eighty-seven-year history in which international leadership would be directly elected by members rather than by delegates. The former system had been rife with favoritism, controlled by the Administration Caucus that had ruled the union and crushed internal dissent since it was created by the UAW’s most famous president, Walter Reuther. A federal monitor was appointed in the wake of a corruption scandal that landed twelve UAW officials, including two former presidents, in prison; the union agreed to hold a referendum on direct elections. In 2021, that referendum passed with 63 percent of ballots in favor.

Shawn Fain, a union staffer and former local UAW leader from Kokomo, Indiana, ran for president on a slate called UAW Members United. The slate was backed by Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD), an internal caucus that had formed in 2019 to push for direct elections. When the membership voted in favor of direct elections, the caucus decided to back challengers for seven seats on the international’s executive board under the slogan “No Corruption. No Concessions. No Tiers.”

Weyer joined UAWD. He had known Fain since 2011. That year, Fain was on the negotiating team for the Stellantis (formerly Chrysler) contract, and Weyer was helping with social media, keeping members informed about the negotiations through Facebook.

“When people would leave comments saying, ‘Oh, they’re trying to screw us. They don’t care,’ Shawn would respond,” said Weyer. “He’d say, ‘I’m a negotiator and I care, and here’s what we’re doing.’”

The two stayed in touch. When Fain was sworn in as the new UAW international president on March 26, 2023, after a runoff election against incumbent Ray Curry that he won by fewer than five hundred votes, Weyer was at the ceremony.

“When I found out that Shawn won, this weight that I didn’t even know I was carrying fell off my shoulders,” said Weyer. “I was just so proud. I was proud of my union.”

After years of corruption and decades of decline, members like Weyer see immense possibilities for a fighting, democratic unionism free of corruption under Fain’s leadership. The UAWD-backed candidates won all seven executive board races, giving them the edge over the Administration Caucus’s six seats on the board (there is also one independent). But it’s easier to change a union president than it is to change a union culture — particularly one in which corruption has been the norm and internal democracy has been all but nonexistent. And if the UAW bargaining convention this week is any indication, the union reformers have a long road ahead of them.

The Union Has Spoken

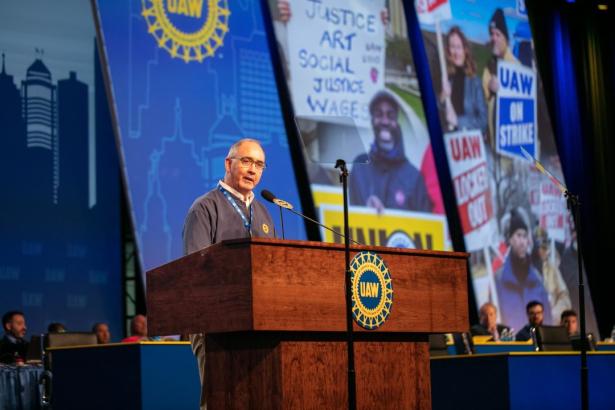

When Fain took the stage at the start of the UAW’s Special Bargaining Convention on March 27, just twenty-four hours after swearing in as president, he opened by saying, “We’ve just witnessed the four most powerful words in a democracy: the people have spoken.”

Fain was presiding over the gathering of roughly nine hundred delegates who had come to Detroit from around the country to determine the union’s priorities for negotiations with the Big Three automakers: Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis. Their four-year master contract, covering some 150,000 members, expires on September 14.

The Big Three agreement once set the bar for auto manufacturing, and manufacturing work of all kinds, across the United States. The standards around pay, benefits, working conditions, and much more helped workers beyond the auto industry demand similar standards from their own employers. As deindustrialization has ravaged factory work and industrial union membership, that pace-setting role has diminished.

Delegates at the UAW Special Bargaining Convention this week in Detroit. (UAW)

The current UAW consists of four hundred thousand workers and six hundred thousand retirees — still the largest industrial union in the United States but down from its peak of around 1.5 million in 1979. Less than half of autoworkers in the United States are UAW, which significantly undermines the union’s bargaining power. The union is on track to lose even more market share as the electric vehicle (EV) industry grows: the Big Three have thus far managed to keep their EV operations out of the UAW’s master agreement, and where such shops are UAW, the workers are differently categorized, paid less and with fewer benefits.

As in other unions, concessionary bargaining and a shrinking membership went hand in hand with corruption, as UAW leaders, closer with management than with their rank-and-file members, managed the decline of their industry. The agreements left workers in an ever-worse position even as the leadership enriched themselves, securing resources for their personal fiefdoms and select allies in the union. The details of such corruption are almost cartoonish: a federal investigation found that senior officials had embezzled millions, spending it on, among other luxuries, golf outings and extended stays at a Palm Springs villa. According to the New York Times, union officials acquired enough “golf bags, sunglasses, shirts and ‘fashion shorts’” on these trips that they used a semitruck to ship the items home to Michigan.

The bankruptcies at GM and Chrysler during the Great Recession accelerated the trend: autoworkers accepted once-unthinkable concessions, giving up cost-of-living-allowances (COLA) and accepting lower-paid tiers with worse benefits for new workers in their shops. With tiers came greater division: unity cannot be built in a shop where workers receive different pay and benefits for equal work.

Now automakers are flush with profits, yet UAW members have not clawed back what they previously handed over. Fain’s election suggests that they may not be willing to accept such a raw deal any longer.

“We’re here to come together to prepare ourselves for the war against our only one and only true enemy: multibillion-dollar corporations and employers who refuse to give our members their fair share,” said Fain from the stage.

Dan Vicente, a UAWD member elected as Region 9 director straight from the shop floor of a manufacturing plant in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, said, “It’s time to get back what we gave up, and we’re not willing to negotiate from a place of no power. We make the products, we provide the services, we are the labor, so the ball is in management’s court. Membership wants us to go and get back what was taken, and that’s our intention.”

Rhetorically, it’s a far cry from the friendly attitude toward employers that characterized Fain’s predecessors. The UAW under his leadership may be shifting away from a posture of accepting defeat and managing decline to that of a fighting union.

But on the convention floor, it was easy to forget that UAW Members United won all leadership elections they contested. The attending delegates were elected in the spring of 2022, when Curry and the Administration Caucus still seemed untouchable. They’re the middle layer of the union, local leaders, many of whom have spent decades supporting the Administration Caucus. Often such loyalty was a strategy to ensure favorable treatment or career advancement; when one toils in the brutal conditions of an auto plant, decamping for the comparatively cushy environs of union staff can be a welcome prospect.

When Fain first took the stage in Detroit, many delegates did not clap. By contrast, when Vice President Chuck Browning, now the union’s highest-ranking official from the Administration Caucus, was introduced, cheers rang out from the delegates of the room representing regions that voted for Curry. Browning comes out of the UAW’s Ford department, and very few of the union’s Ford locals went for Fain.

Throughout the proceedings, mentions of Browning served as a proxy for the division between the old and new guard, a way for those who do not support the reformers to express their displeasure with the changes underway. As one delegate put it in response to a procedural change proposed by a UAWD delegate, “The rules have worked for us in the past, and we need to keep them the way they are.” Such resistance helped defeat a resolution to include COLA in initial bargaining proposals: opponents said it would “handcuff” bargaining committees.

“Understand one thing when you look at that body of delegates: we have a seventy-year entrenched caucus that did a phenomenal job in the past of getting delegates elected who support their cause or support their issues,” said Fain when pressed on the palpable division on the convention floor. “Those delegates were elected prior to the last convention, so it’s still a very pro–Administration Caucus delegation. But if you look at the election, and you look at where the membership is, I think it’s two different stories.”

He and his fellow reformers won’t be able to rely on such delegates when building support for their more aggressive agenda: not only clawing back COLA and job security, eliminating tiers, rolling EV plants into the master agreement, and ending the prolonged temporary status for new workers, but pushing for thirty-hour workweeks, building cross-border solidarity with workers abroad, expanding health care coverage to include reproductive care, and gaining the right to strike an employer nationally over plant closures.

While some staff and local leaders who supported Curry will get on board with Fain, others will refuse to cooperate, either doing the bare minimum or actively sabotaging reformers’ efforts, hoping to weather the four years of his term until the next leadership elections. (Reporters who diligently tried to speak with Curry supporters, including me, did not have much luck, though Jane Slaughter and Keith Brower Brown at Labor Notes had some success.) Changing course will require Fain and his allies to go directly to the members, speaking to them at the worksite and the plant gates, building their confidence and the unity that prior leadership systematically undermined.

A telling change was apparent from the moment the convention opened: at previous gatherings, staff liaisons choreographed the proceedings by handing certain delegates scripted statements and coordinating with the leadership on stage to determine who to call on and in what order. Delegates were often handed a colored envelope, which they would then hold up; those on the stage would look out and see the envelope, knowing to call on that person next. At this year’s gathering, there were no liaisons on the floor.

Not everyone was happy about the unprecedentedly democratic nature of the convention. Late one evening, I was speaking with a well-known reformer. We had been interrupted repeatedly by fellow delegates who wanted to shake his hand, some of whom were supporters of the old guard but wanted to show their respect. But one man approached us and quickly became belligerent. When the reformer calmly responded, saying, “OK, thank you, brother,” the man shouted, “I’m not your brother. Don’t ever call me your brother.” He made his opinions about the reform caucus clear: “Fuck you and fuck that UAWD shit and go to hell.”

A Union That Still Strikes

Despite such resistance, there are factors in reformers’ favor. The UAW was built through strikes. The 1936 Flint sit-down strike is the union’s origin story, and while much in the auto industry has changed in the intervening years, assembly lines still can’t function without workers.

UAW members still strike — strike-authorization votes generally pass by an overwhelming margin. But under previous leadership, strikes were top-down affairs. Leadership might inform workers that they would be striking, without offering much information beyond how to access strike pay. In this model, workers are passive recipients of leadership’s diktats and kept in the dark about the bargaining process rather than included in a contract campaign to pressure the employers. Yet when the day came to walk out, members still downed their tools — even in 2019, when a major corruption probe was announced just weeks before an auto strike.

Indeed, one of the few resolutions to be pulled out of committee and adopted at the convention concerns honoring picket lines; supporters cited a 2019 incident in which GM workers were told to cross the picket line of striking Aramark workers who were members of their locals. The Teamsters have the right to respect picket lines in their contracts, and the UAW members want that too. The task ahead for reformers is to make use of that militant tradition, shaking off the decades of stultifying Administration Caucus rule that have carefully managed it and placing it once again in the hands of the rank and file.

The resolution about honoring picket lines was a UAWD priority. Another concerning inclusive bargaining units in higher education passed as well. The UAWD delegation only numbered around fifty or so, a small minority, but their mood was celebratory, even jubilant. That they managed to get a handful of resolutions pulled out of committee, and pass several, means that the caucus is winning over additional members, building toward a majority in favor of a union that goes on the offensive.

Upon stopping by the conference room that operated as UAWD headquarters at the end of the convention’s first day, Fain teared up: “I’m so proud to be a member of this caucus.” When he came to the caucus’s happy hour at a nearby bar later that evening, he stayed so long chatting with members that his staff began arguing about how to get him to leave in time to be well-rested for the following day.

A delegate stands and speaks at the UAW Special Bargaining Convention. (UAW)

It’s a dynamic without comparison in recent US union history. While the Teamsters just elected Sean O’Brien, a challenger to former president James P. Hoffa’s preferred candidate, as international president, O’Brien is not a member of Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU, a union reform caucus). O’Brien and TDU worked together to oust the Hoffa regime, and the alliance remains intact as the union prepares for a possible strike at UPS this summer. But for a reform caucus to win the presidency as well as several seats on the international executive board in the first direct election in UAW history is a different story.

“There’s a fire in the labor movement, and this election is just a reflection of that,” said Vicente, the Region 9 director. “We have independent unions across this country popping up left and right. The Teamsters are reforming, the UAW is reforming, and we see ourselves not just as the directors of these regions now, but as militants in a labor movement that’s going to have to fight back against the corporations that have reaped untold amounts of wealth off of our backs.”

Fain’s victory was nail-bitingly close, and turnout was dismally low. But the reformers’ sweep is a mandate for those who want to return the UAW to its former outsized role. Much like the Teamsters must organize Amazon and other nonunion competitors if they’re to survive, so too must the UAW find a way to break through in nonunion auto plants.

If the union doesn’t aggressively organize EV plants in particular, it is setting itself up for further decline. Allowing automakers to keep their joint-venture battery plants outside of the master agreement ensures that such work will be compensated at a significantly lower rate. Asked about this problem, Fain acknowledged it, describing the union as “already behind in this battle.”

“I know that I have a vested interest in keeping gasoline engines around as long as possible because there are a lot of jobs involved,” said Dan Denton, who works in the jeep unit of the Stellantis Assembly Plant in Toledo, Ohio. He noted that he and his coworkers still enjoy far better wages and benefits than are on offer in the area’s other jobs. For Denton, EVs raise the specter of fewer auto mechanic jobs and the loss of the engine line in an assembly plant.

But he wants the UAW to take the lead in planning the transition and ensure that workers in plants that shutter have somewhere to go. Said Denton, “We have to figure out something to do with the wrench-turners like me who we won’t need anymore.”

The UAW is the largest union for manufacturing workers in the United States, but it is also the largest for graduate student workers. UAWD reflects such cross-sector membership, and the caucus’s room at the convention offered a rebuke to concerns about whether grad students and autoworkers can coexist in the same union.

The first time I stopped by, a Harvard grad student and an autoworker were discussing a resolution about pensions. While the grad student noted that the issue wasn’t particularly relevant for her, she was helping strategize about how to pass the resolution. She suggested resolution language members could cite to make the strongest argument. “I do my homework,” she explained, eliciting appreciative laughter from the manufacturing workers in the room. When I mentioned the graduate union members to Vicente, he called them an invaluable asset.

“As an auto worker in manufacturing, when I found out that we have grad students, I was shocked,” said Vicente. “But then I also thought, why have we never talked to these dudes? You hear the words ‘Harvard graduate,’ and it’s like, ‘Oh my God, these are the most highly educated people in the world. We should be tapping into that resource.’ Then you meet them and they have a wealth of knowledge, and they’ve been able to help us to try to organize ourselves.”

A Union That Goes Beyond the Factories

The UAW once not only set standards for the labor movement, but also put its heft behind other movements. Many of the most important progressive developments of the twentieth century outside of the labor movement have involved the UAW. Reuther was friends with Martin Luther King Jr and spoke at the March on Washington — the union paid the bill for numerous aspects of the rally that day — and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) leaders wrote the Port Huron statement on UAW property.

In his opening remarks, Fain quoted from Martin Luther King Jr’s final book, Where Do We Go From Here?, written the year before King’s assassination. At the time, the civil rights movement had won the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but economic and political discrimination persisted, and the movement was debating what to do next. Wrote King:

We have left the realm of constitutional rights and we are entering the area of human rights. The Constitution assured the right to vote, but there is no such assurance of the right to adequate housing, or the right to adequate income. . . . Achievement of these goals will be a lot more difficult and require much more discipline, understanding, organization, and sacrifice.

“Dr. King’s words resonate with us today,” said Fain from the stage:

Our union is moving from rights on paper to rights in action. We’ve won the right to vote for our top leadership. We have the right to strike. We have the right to a grievance procedure. We have the right to arbitration, to collective bargaining. But we have not yet won the rights that will fundamentally change this union and change this country.

We’ve not yet won racial and economic justice in the workplace for all of our members. We’ve not yet won equal pay for equal work with an end to tiers in our contracts that divide our members. We’ve not yet won an end to plant closures that destroy our working-class communities and tear our families and our members’ lives apart. We’ve not yet won a higher education system that creates good jobs and provides free education as a public good. We’ve not yet won retirement security and health care and pensions for all. We’ve not yet won rights on the job for the hundreds of thousands of unorganized auto workers and millions of other workers across the country. Not yet, but I believe we will.

Three of Fain’s grandparents were UAW members, and he sees himself as part of a movement that has been decades in the making. While he has won the top seat, he knows that achieving reformers’ expansive vision will take much more work. In speaking with me about his victory’s lineage, he mentioned New Directions, a 1980s reform movement within the union.

New Directions managed to get one of its founders, Jerry Tucker, elected as Region 5 director, but the Administration Caucus blocked him at every turn. By the time he was officially installed as director after a rerun election in 1988, two years after the original vote, he had a mere nine months left in his term. The staff who were meant to be under his direction spent that time resisting his vision and preparing to unseat him, an attempt at which they were ultimately successful.

View of a Civil Rights demonstrator as he holds a sign that reads “UAW (United Auto Workers) Says: Registration, Constitution, Yes; Segregation, Jim Crow, No” near a tent during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. (Roosevelt H. Carter / Getty Images)

Members of New Directions were present at this year’s convention, organizing with UAWD. Stopping by the UAWD room at the convention center, I found longtime union reform activists Mike Cannon, Wendy Thompson, Diane Feeley, Judy Wraight, Bill Parker, Ron Lare, and Frank Hammer in discussion with younger autoworkers and graduate students. On the convention’s second day, Cannon and Hammer led a discussion of New Directions. One UAWD member came straight from his shift at the Dearborn Truck Plant to attend; he was still wearing his jumpsuit.

As New Directions faded, the holdouts, largely retirees, formed the Autoworker Caravan, which kept the dissident spirit alive by criticizing concessionary contracts and creating leaflets to help members organize against the givebacks. In 2010, having run for delegate for the first time and won, Scott Houldieson, a Local 551 member at Ford’s Chicago Assembly plant since 1989, saw a flyer for a meeting in the Detroit area just before that year’s constitutional convention. The purpose was to discuss the recent concessions; he decided to check it out.

Houldieson hadn’t always been a rabble-rouser, but local corruption and concessionary contracts — the 2007 agreement that introduced tiers and the 2009 contract that suspended COLA — irked him. When he walked into the hotel room where the 2010 meeting was taking place, he was greeted warmly.

“Until that time, I had no clue what New Directions was,” said Houldieson. “Nobody talked about it in my plant, or if they did, it was in whispers.” He joined the Autoworker Caravan. They were lonely years, but Houldieson was determined to fight back against concessionary contracts, even if it meant battling the Administration Caucus. He became a familiar presence at UAW conventions, speaking up from the floor so often that at the 2023 convention, seemingly every elected official on stage knew him. When a handful of members began discussing a push for direct elections in 2019, the nucleus of what would become UAWD, Houldieson was there.

Houldieson, who is currently the chair of UAWD’s steering committee, was ebullient about his caucus’s achievements at the convention: “We’ve exceeded our expectations and punched way above our weight class. All we really want is union democracy so we can make decisions on behalf of the membership at this convention. We don’t want top-down strategy because look where it got us. The membership doesn’t want to go there again.”

“The UAW Wasn’t Founded by Asking for Permission”

“This week, I’ve heard some talk about what we can’t do, about what the law says or about this or that subject of bargaining,” said Fain in his closing remarks on the final day of the convention: “And the law has its place. But the UAW wasn’t founded by asking for permission. The founders of this union didn’t wait for the law. They didn’t worry about the law. They wanted their dignity, and they wanted their fair share, and they did what the hell they had to do to get it.”

Applause broke out at several points in the speech, and by the end, almost the entire delegation was on its feet. Such unity was helped by a signal from the stage: earlier in the day, Browning, the vice president and Administration Caucus member, said that they would not go into negotiations as a divided union. “Let’s support our president and International Executive Board,” he told the crowd. One reformer did his part to encourage such unity by standing behind the delegates from one of the most recalcitrant UAW regions, loudly shaming them into standing up.

After the convention concluded, I made my way to the UAWD room for a debrief. Weyer was standing outside the door. When I asked him how he felt now that the convention was over, he smiled. “I’m optimistic. Aren’t you?”

CONTRIBUTORS

Alex N. Press is a staff writer at Jacobin. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Vox, the Nation, and n+1, among other places.

“Nationalism,” the new issue of Jacobin is out now. Subscribe today and get a yearlong print and digital subscription.

Spread the word