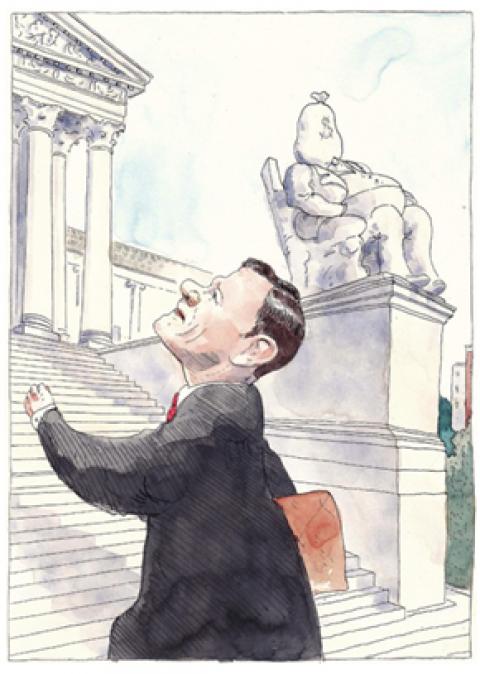

Think the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United was bad? A worse one may be on the horizon.

To recognize the problem, it’s necessary to review some of the Court’s gnarled history on the subject of campaign finance. In Citizens United, which was decided in 2010, the Court rejected any limits on what a person or corporation (or labor union) could spend on an independent effort to help a candidate win an election. Thus the rise of Super PACs; that’s why Sheldon Adelson could spend sixty million dollars to help Mitt Romney in 2012. But, though Citizens United deregulated independent expenditures on behalf of candidates, the case said nothing about direct contributions to the candidates themselves.

That’s where the new case comes in. Current federal law allows individual donors to give up to two thousand six hundred dollars to any one candidate during a single election. In addition, they can give only an aggregate hundred and twenty-three thousand dollars to candidates, political action committees, and parties over a two-year period. Shaun McCutcheon, an Alabama Republican, wants to give more money to the candidates he supports, so he has sued to invalidate the rules limiting the over-all amounts he can give. (Indeed, the patriotically minded McCutcheon wanted to give “$1,776” to enough candidates to exceed the current limits on direct contributions.) The Supreme Court will hear his case in the fall, and he has a good chance of winning.

To see why McCutcheon may win, one must examine the strange reasoning that governs the Supreme Court’s decisions on campaign finance. In his brief to the Justices, McCutcheon makes an argument that is breathtaking for its candor. He says that when Congress first upheld limits on contributions, in the 1976 case of Buckley v. Valeo, the limits on aggregate giving served a useful purpose. Without the ceiling, the Court explained, a person could legally “contribute massive amounts of money to a particular candidate through the use of unearmarked contributions to political committees likely to contribute to that candidate, or huge contributions to the candidate’s political party.”

But that, McCutcheon points out, was before the days of Citizens United. Now, he implies, Citizens United has undermined so many of the old rules that they are kind of irrelevant at this point. Indeed, the lower-court judge who considered the McCutcheon case upheld the existing rules but raised the “possibility that Citizens United undermined the entire contribution limits scheme.”

The reason the contribution levels might be in jeopardy rests on the rationale the Justices now demand for all campaign-finance limits. According to Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s opinion in Citizens United, the government’s interest in preventing the actuality and appearance of corruption is “limited to quid pro quo corruption.” Congress can regulate campaign contributions only to stop contributors from demanding, and receiving, quid pro quos. The Court forbids other justifications for contribution limits—like levelling the playing field. Quid pro quos are, of course, very difficult to prove. So unless the government can prove that the limits on aggregate contributions prevent quid-pro-quo corruption (and how, really, can the government do that?), these rules might fall, too.

Such an outcome is especially likely because the current Court has such an exalted idea of the importance of campaign contributions as a form of individual expression. In other words, money equals speech. The speech of wealthy people is a source of particular, almost poignant concern. As Justice Kennedy wrote, the fact that contributors “may have influence over or access to elected officials does not mean that those officials are corrupt.” Indeed, he observed further, “political speech cannot be limited based on a speaker’s wealth.”

Citizens United was not an aberration for this Court. It emerged from a definite view about the intersection of campaigns and free speech. The Justices in the majority are engaging in a long-term project to deregulate campaigns. A blessing on unlimited aggregate contributions is the next logical step for them to take—and they have five votes.

Spread the word