Photos by Andri Tambunan

On July 22, the day after President Biden announced he wouldn’t seek reelection, members of Carpenters Local 971 filed into their union hall in Reno, Nevada, for their monthly meeting. During a break, Adrian Davis, a self-described “political nerd” and union member of five years, asked a fellow carpenter for his thoughts on Kamala Harris. The carpenter shook his head, saying he planned on voting for Donald Trump, as he had in the past.

Incredulous, Davis rattled off a list of legislation Joe Biden had signed: the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, the CHIPS and Science Act. Just north of town, Carpenters union members were expanding U.S. Highway 395. Out east, in the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center, they were building a massive battery recycling plant. And just weeks before, the Biden-Harris administration had selected the area as one of 12 regional tech hubs to receive a second round of funding from the federal government, along with hubs in Wisconsin, New York, Georgia and Florida. The new funding, of $21 million, will support workforce development in Northern Nevada’s burgeoning lithium industry, in what promises to be a boon for local construction unions.

“You know all the work we’ve been doing?” Davis said. “That’s Biden money.”

“He had no idea about any of that,” recounted Davis a few days later. The 46-year-old stood outside the union hall, a red-white-and-blue bandanna wrapped around his dreads. “I don’t know if it made an impact, but at least I shared information. If you’re going to check a box, you should at least know what you’re checking.”

The interaction in the union hall highlights a major project for organized labor in swing states like Nevada: to ensure their members understand how they have benefited from federal policies and legislation. In Washoe County, home to Reno and the second largest population center in the state outside of Las Vegas, the results of federal action are written across the landscape, sparked by massive government investment in infrastructure and clean energy and carried out to a large extent by union construction workers.

“This region is on fire,” said Rob Benner, the executive secretary treasurer of the Building & Construction Trades Council of Northern Nevada, which represents 6,000 members. “Everybody’s busy, everybody’s working overtime.” Last year, an analysis by the Center for American Progress found that federal investment in clean energy was higher here than almost anywhere else in the nation.

The area is home to what people out here call the Lithium Loop, buoyed by the largest proven source of lithium in the U.S., a critical component of electric batteries. In March, the Department of Energy announced a $2.26 billion loan commitment to a subsidiary of Lithium Americas, which will help build a lithium processing plant to be used in batteries for General Motors. Lithium Americas has already signed a collective bargaining agreement with the building trades, and the project is estimated to create 1,800 jobs during construction.

“Trump has made it part of his platform that he’s going to destroy electric cars, and if those federal funds collapse, we might not have these projects,” said Wendy Colborne, the communications director of the Trades Council. “A lot depends on November, and we’ve been trying to communicate that to our members.” (Trump has backed off his campaign against electric vehicles somewhat since forging his close alliance with Elon Musk.)

Albert DeVita demonstrates the operation of the Vermeer PD 10, a pile driver used for solar field installations. DeVita provides training with the equipment at the Northern Nevada Laborers Training Center in Sparks.

Biden won Nevada and its six electoral votes by just 33,596 votes. Before Biden announced he wouldn’t seek a second term, polls showed Trump enjoying a significant advantage in the Silver State and making large inroads among Hispanic voters. Since Harris became the nominee, however, the race became a dead heat before Harris took the lead.

Holding onto and possibly growing the support of Nevada’s union households—who, according to exit polls, broke 58 to 39 for Biden in 2020—will be crucial. Construction union members, who skew more towards Trump, also represent an opportunity to make Democratic inroads if unions can convincingly link federal legislation with their own members’ livelihoods.

Laborers Union Local 169 represents about 1,600 construction workers in Northern Nevada. Its Training Center is located 15 miles east of Reno, at the beginning of the sprawling Tahoe Reno Industrial Center. The TRIC bills itself as the largest industrial park in the world, located in a barren stretch of land with signs that warn drivers to look out for wild horses. It is home to a Tesla Gigafactory, countless logistics buildings and lithium-related companies. Streets have names like Electric Avenue and Battery Boulevard.

Albert DeVita has been the training director of Local 169 for six years. During that time, the number of union apprentices has tripled, from 40 to 120, and he will need hundreds more workers for future solar projects funded with clean energy tax breaks. As the first point of contact for new union members, DeVita stresses the connection between federal policy and union jobs. About 2020, he said, “A lot of people voted the wrong way. There’s going to be a major effort to mobilize our members this year.”

One of those members is Guadalupe Lopez, who joined the Laborers local in 2021 and often works overtime, which is how she prefers it. She is currently a “flagger,” directing traffic around construction on U.S. 395. Funds come from the infrastructure bill, which to date has invested $85 million in Washoe County for transportation projects. Earlier this year, she leveled dirt for a solar project of Ormat Technologies, a renewable energy company that has described the tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act as a key driver of its growth. The Biden Administration estimates that the act will bring an investment of $2.7 billion in large-scale clean power generation and storage to Nevada by 2030.

Lopez echoed the sentiments of other construction workers: While she worried about inflation, her No. 1 concern was having steady work. “What I care about with politicians is who is going to give us the most work,” she said. “That’s why I hope Trump wins.” She wasn’t aware of the federal legislation that had helped keep her hours high, and she has reservations about Trump’s rhetoric targeting Mexican immigrants—she has family that she visits in Tijuana, Mexico. “But Trump knows how to make the economy work and create more jobs,” she concluded. “That’s the most important thing.”

After Lopez departed, Eloy Jara, the union’s business manager who had sat in on the interview, let out a sigh. “As you can see, we have a lot of work to do on member education.”

The Redwood Materials battery recycling and materials production facility in McCarran

Lopez isn’t alone. This February, a report by the Center for American Progress looked at the building of an electrical vehicle battery facility in Tennessee that received significant financial help from the federal government. While the union workers spoke of the jobs as “life-changing,” many were unaware of the public investments that had been made. In making the connection between public policy and job creation, the report concludes, “Unions are likely to be especially important players.”

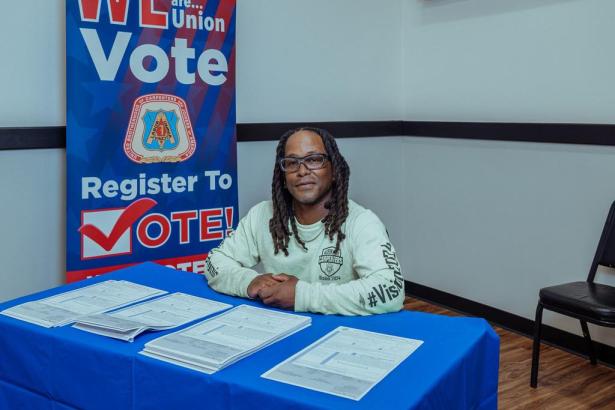

“I’ve been told by older members, ‘You’ve got to vote your paycheck,’” said Omar De León, 26, a Carpenters Local 971 member who recently joined the union’s political committee hoping to learn more about how public policies impact union members. He now brings flyers to his worksite highlighting Biden policies that supported union jobs, and said they’re targeting the 28% of members still unregistered to vote. “We’re trying to get those numbers up.” Some workers, said De León, are skeptical of the Democrats, linking them to inflation or high interest rates. Others simply don’t see the connection between politics and their life.

A Trump victory could make the connection more concrete. The Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office (LPO) has been key in supporting the burgeoning lithium industry. The office has provided significant loans under the Inflation Reduction Act—$2.26 billion to Lithium Americas and $2 billion to Redwood Materials, a company specializing in lithium processing and recycling.

“Under Trump, the LPO was essentially gutted,” said John Jacobs, a senior policy analyst at the Bipartisan Policy Center. And Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s blueprint for a second Trump term, calls for the office’s outright elimination. Trump has recently distanced himself from the plan, which was authored by his allies and former aides.

“If Trump wins a second term and those loans haven’t closed before inauguration, it’s very possible that the administration could walk away from them,” said Josh Freed, senior vice president for the Climate and Energy Program at Third Way, a center-left think tank. “The risk under Trump, who has shown that he is a chaos agent, is huge. It would be like setting an arsonist loose on the emerging lithium economy of Northern Nevada.”

In mid-August, the Building & Construction Trades Council of Northern Nevada joined the state’s AFL-CIO in a door-to-door canvassing of their membership, a shift from previous years when outreach was directed at the general electorate. The goal will be to make the connections between politics and their lives explicit. “We need to make sure they understand what the administration has done for labor for the last four years and the impact it has had on this region,” said Benner. “The future is so bright, but that whole economy could evaporate overnight.”

Gabriel Thompson is an independent journalist who has written for publications that include The New York Times, Harper’s, New York, Slate, and The Nation. His most recent book is ‘Chasing the Harvest: Migrant Workers in California Agriculture.’

Capital & Main is a nonprofit publication that reports on two of the most pressing issues of our time: inequality and climate change. Winner of hundreds of awards, Capital & Main has had stories co-published in more than 150 media outlets, from USA Today, Newsweek, The Guardian and Fast Company to The American Prospect, Grist, Slate and the Daily Beast. Our reporting has led to significant impacts at the national, state and local level. Donate to Capital & Main

Spread the word