I have two beautiful daughters. But the journey to bring them into the world nearly broke me—physically, emotionally, and financially.

It took three years of infertility treatments to get pregnant the first time and the cost drained our savings. One round of treatment can run upwards of $50,000—just for a single ovulation cycle, paid entirely out of pocket. And when we tried to fight our insurance denials, we were told there was a “medical alternative”: don’t have a baby.

After all that, our first child died in a stillbirth, which was traumatic and heartbreaking. When I finally made it to my third pregnancy, I hemorrhaged. I still remember the panic in the room, the alarms, the fading voices. And afterward? I had no paid maternity leave unless I used up my sick days. I was expected to bounce back—physically, mentally, professionally—as if nothing had happened.

Our childcare costs are now almost as high as our mortgage.

This is not a rare experience. And honestly, I’m one of the lucky ones. I was able to get pregnant eventually, as I had access to personal support, excellent doctors, and a hospital.

But all of this is why the current national conversation about declining birth rates feels so disconnected from reality.

A national conversation is gaining momentum around declining birth rates

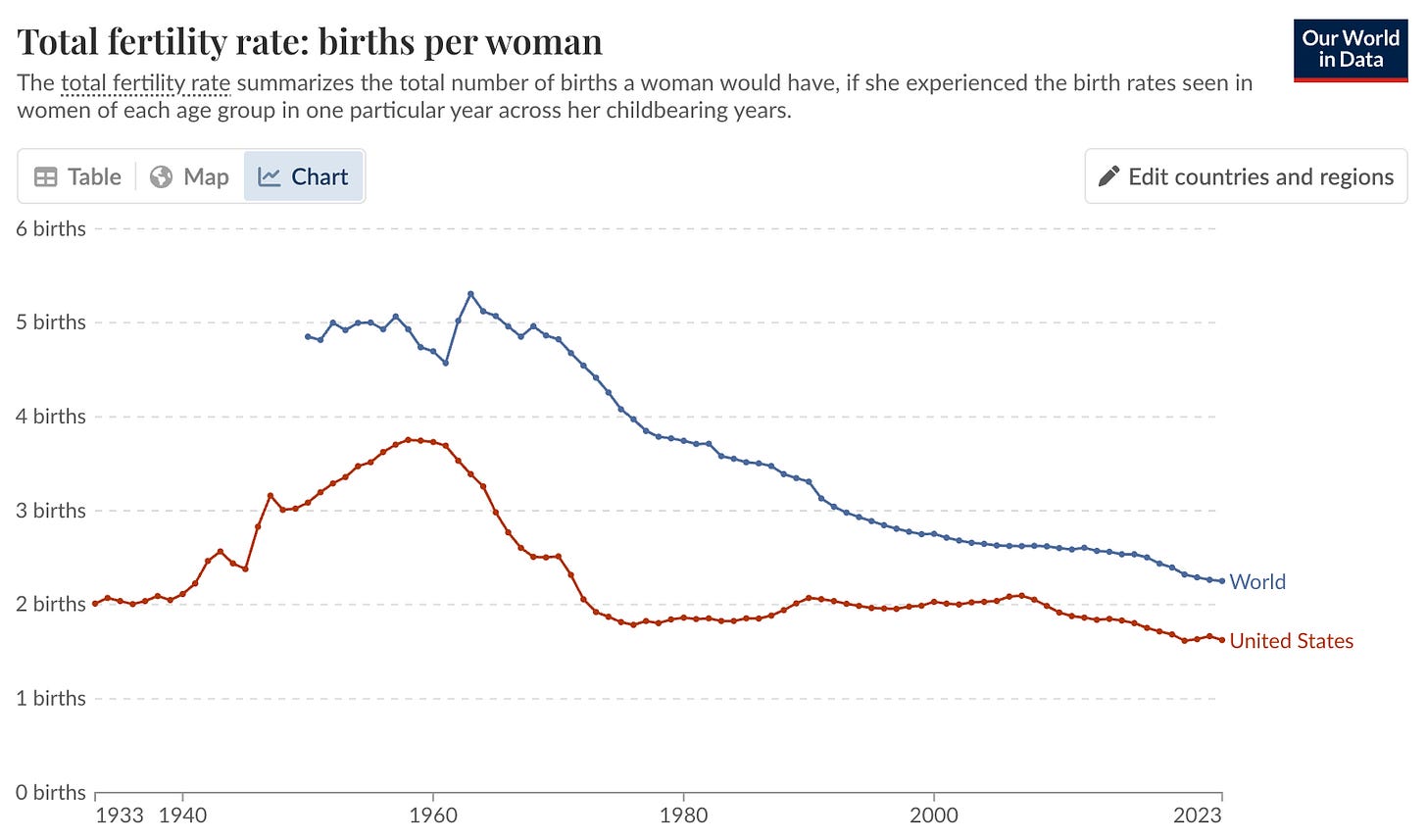

In the U.S.—and across much of the world—fertility rates are falling, and populations are projected to shrink.

The reasons people are worried vary. Some fear a loss of global influence or long-term human survival. Others approach the issue through religious, political, or ideological lenses—or just out of curiosity. Whatever the motivation, the question keeps coming up: What can we do?

In response, the new administration—guided in part by Project 2025—is considering financial incentives to encourage people to have more children. Ideas include education, like on menstrual cycles, or a “National Medal of Motherhood” to mothers with six or more children, as well as financial incentives like a $5,000 cash baby bonus or Fulbright scholarships reserved for mothers.

Globally, paying families to have children has yielded mixed results. In Russia, for example, payments ($10,000) have increased fertility rates by about 20%. However, in Canada during the 1970s, similar efforts yielded only a short-term increase.

So no—we don’t need to blindly throw spaghetti at the wall. We have the evidence: if we want people to have more children, we need to create a society that actually supports parents.

And right now, the U.S. is nowhere close.

1. Access to affordable care is not readily available

Even with insurance, the cost of prenatal care, delivery, and postpartum support can put families under serious financial strain.

Infertility treatments in particular are prohibitively expensive. But when states mandated insurance coverage, birth rates increased by 32%. The connection is clear: covering care works.

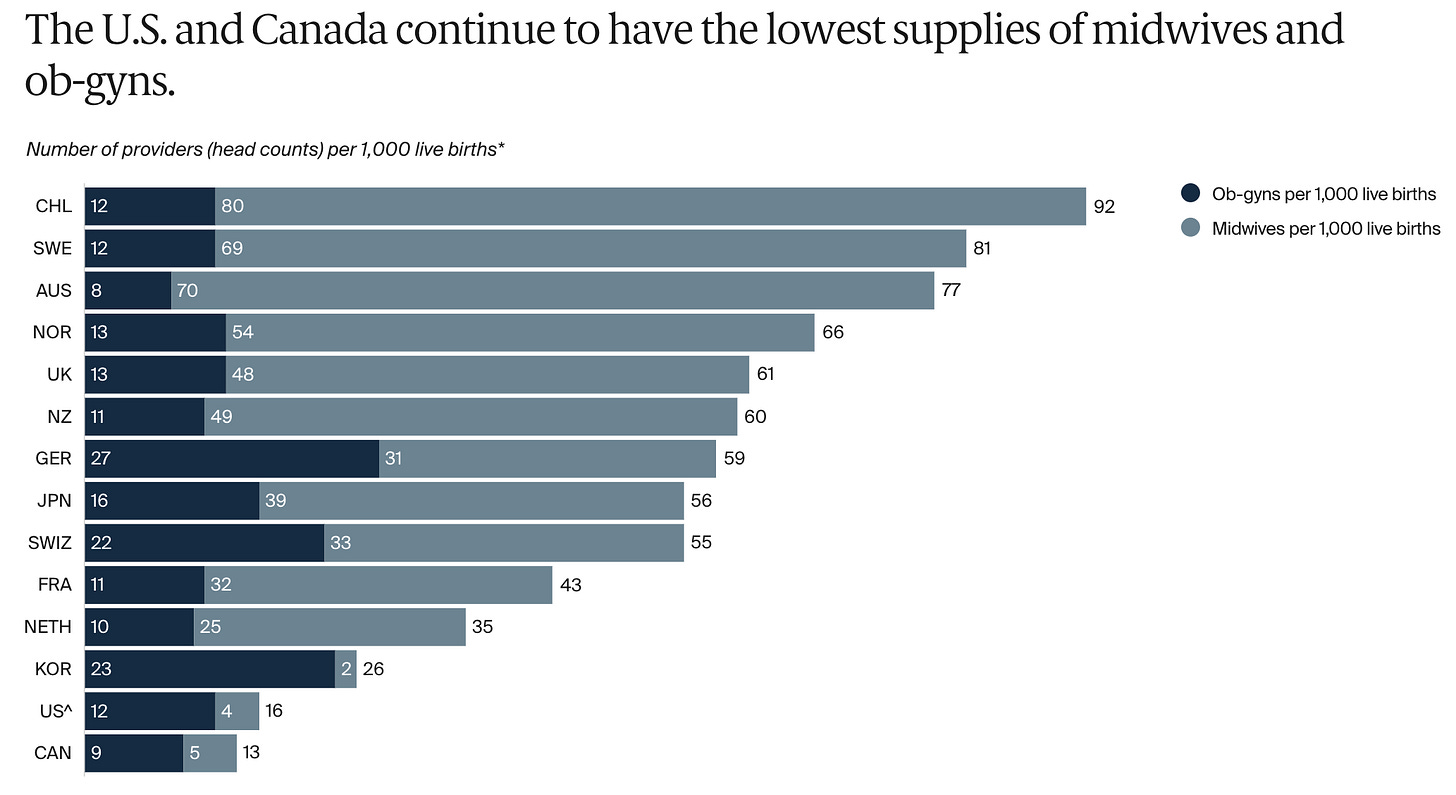

Access to care is another problem. More than 2 million women of reproductive age live in “maternity care deserts”—areas with no OB-GYNs, no midwives, no hospitals offering obstetric services. That’s more than 1,000 counties where pregnancy care is out of reach. The U.S. has one of the lowest supplies of midwives and OB-GYNs compared to other high-income countries.

Source: Commonwealth Fund

2. There’s little support for new parents

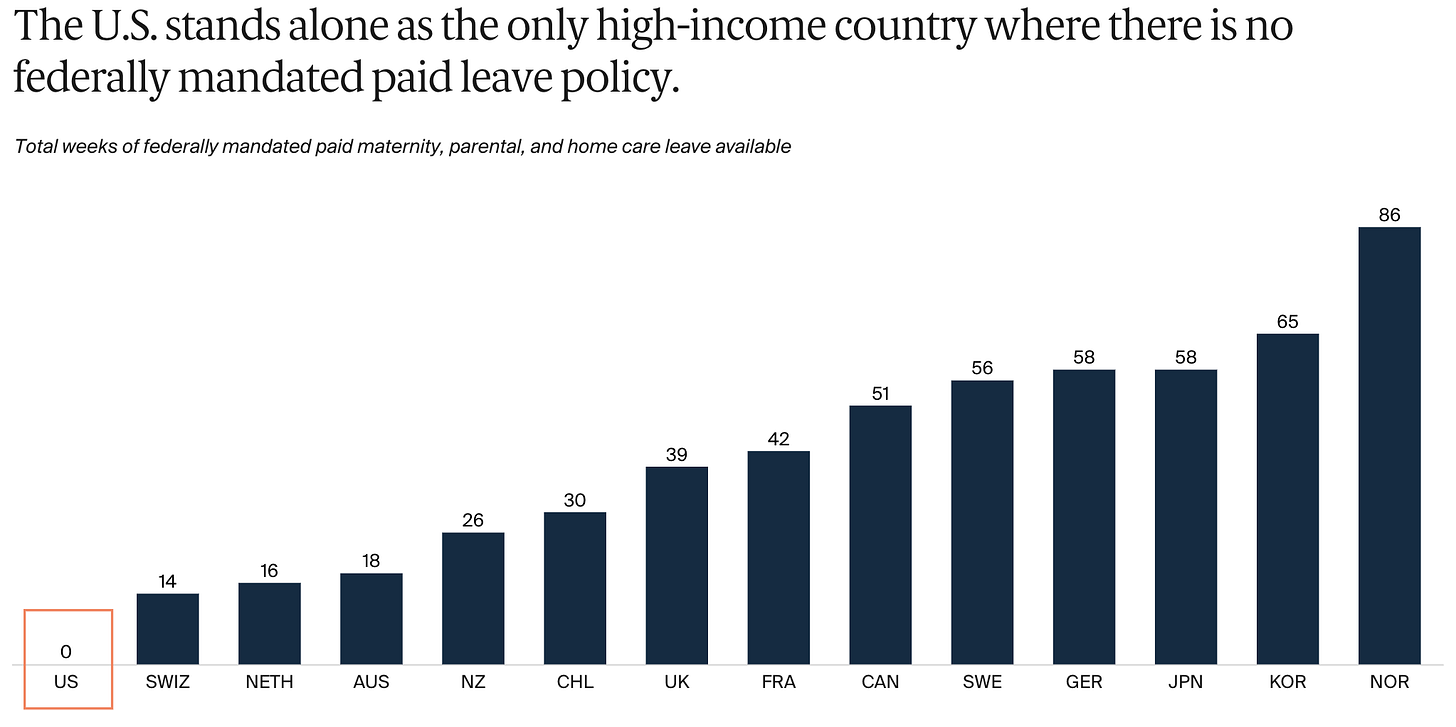

In some parts of the U.S., paid maternity leave simply doesn’t exist. When I had my daughters in Texas, I had zero paid time off unless I used my sick leave. A friend of mine went back to work just two weeks after giving birth. Two weeks.

California, where I live now, offers six weeks of paid leave. But compare that to countries where parents receive six months, nine months, even a year of leave. The difference in recovery, bonding, and mental health is massive.

Source: Commonwealth Fund

And yes—paid leave increases birth rates. After the U.S. implemented 12 weeks of unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act in 1993, the probability of a first birth rose by 5% each year.

3. Raising a child is financially daunting

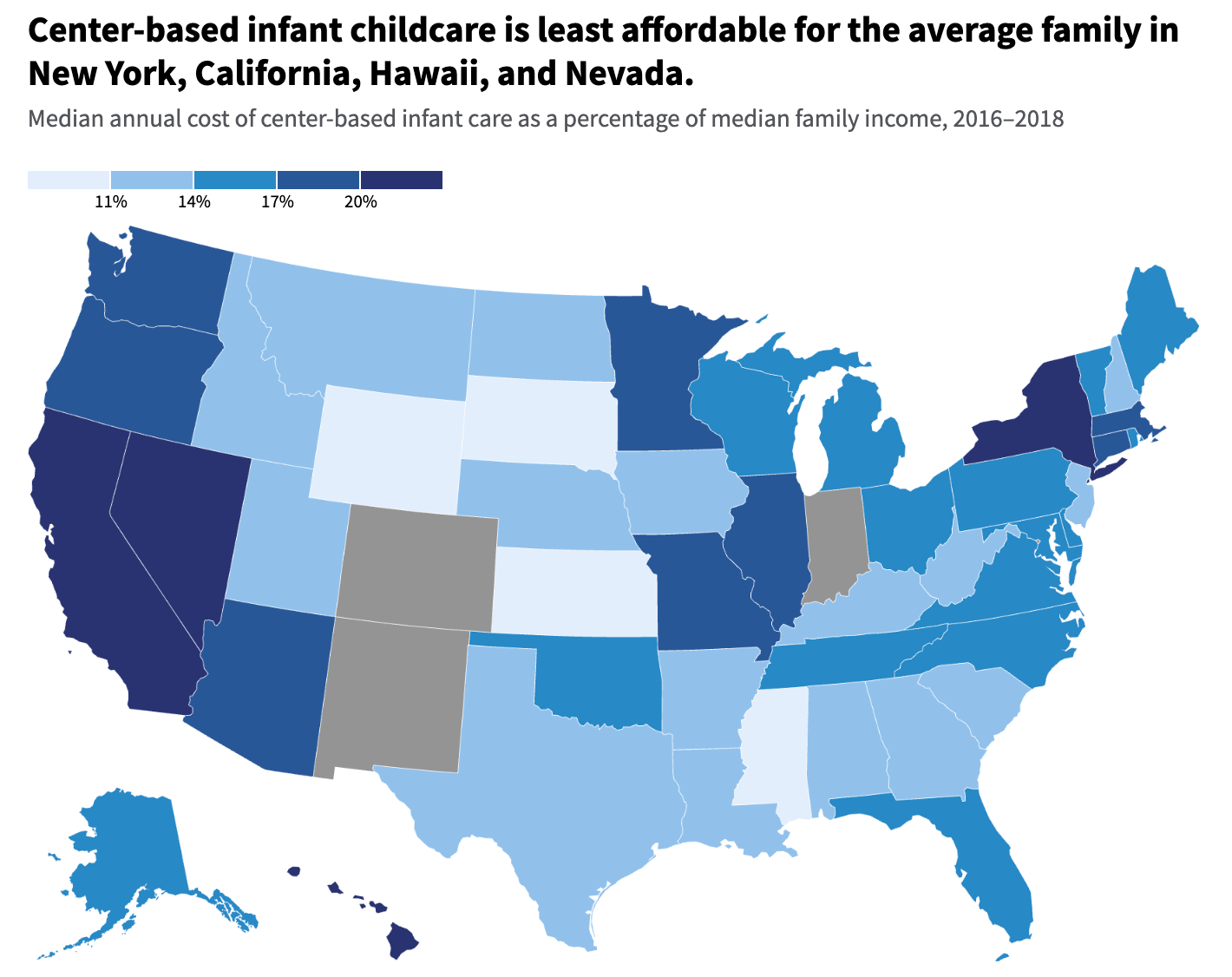

Childcare is second to rent—or more. In some states, the cost of infant care rivals the cost of a mortgage. In some states, it can require up to 19% of a family’s income. The Department of Health and Human Services sets the affordability benchmark for childcare at no more than 7% of a family’s annual income, meaning the average cost of childcare is unaffordable for many families.

Source: USA Facts

And that’s if you can even find a spot. Childcare deserts are common, especially in rural and low-income communities. Many parents are left patching together care, paying out of pocket, or leaving the workforce entirely—usually moms—because the math just doesn’t work.

But again, the data is clear: expanding access to childcare increases fertility. In some studies, a 1% increase in childcare coverage led to a 0.2–1% increase in fertility.

4. There’s a climate of fear

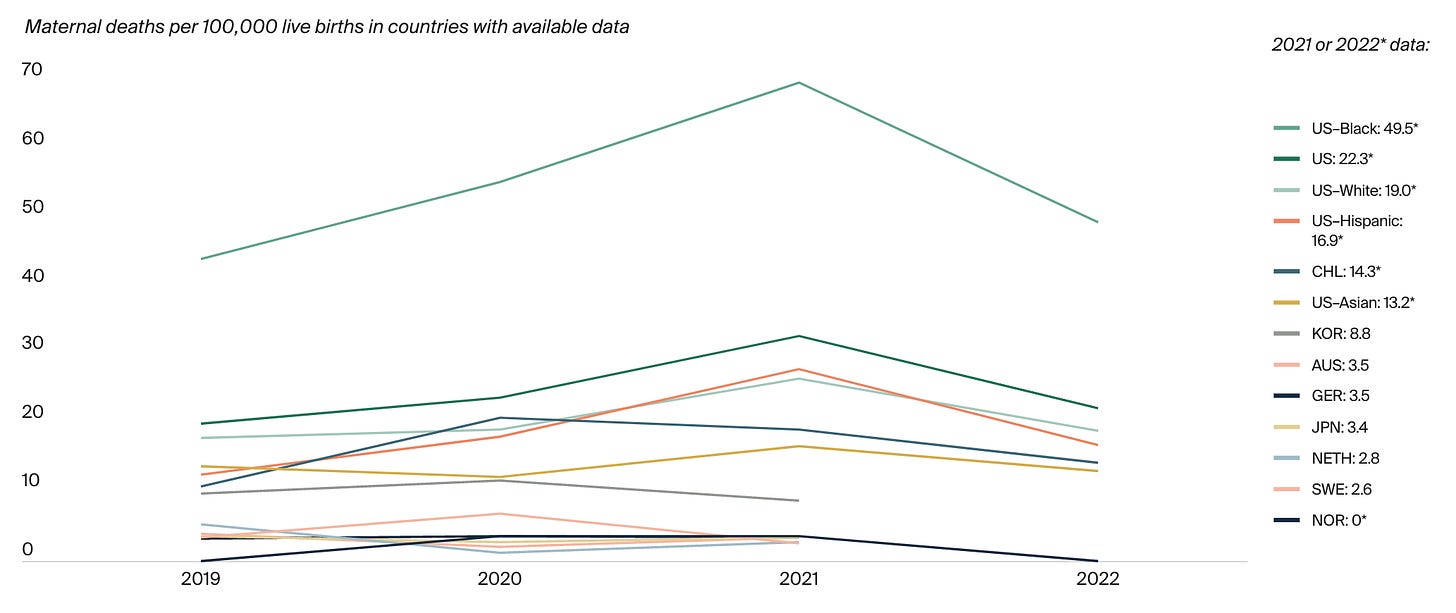

We don’t talk enough about this: the U.S. has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the developed world. And for Black women, the risk is even higher—nearly three times higher than for white women.

This isn’t just a statistic. It’s a fear many of us carry when considering pregnancy.

Maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in countries. Source: Commonwealth Fund

And in some states, that fear now includes criminalization. There are cases where women have been investigated after a miscarriage or pregnancy complication—sometimes by a nurse or a family member.

To make matters worse, some states are even proposing surveillance tactics like monitoring wastewater to track birth control and abortion pill use.

Even thinking about pregnancy now comes with fear, judgment, and potential punishment. This fear doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It influences how people think about their health, autonomy, and safety when considering pregnancy.

5. Programs that support women are being dismantled

While asking women to have more children, we’re dismantling the very infrastructure that supports their health.

-

Just this week, one of the long-running studies, called Women’s Health Study, a critical source of data on women’s health, was shut down.

-

The Office of Women’s Health has now been eliminated at CDC.

Bottom line

People aren’t having fewer children because they don’t care about family, faith, or their future, or the future of this country. They’re having fewer because the system makes it too hard, too risky, and too expensive. A $5,000 payment is a drop in the bucket compared to what is required of families in this day and age.

If the government wants to be part of the solution, it shouldn’t just throw out incentives. It should invest in the foundation: affordable care, parental leave, safe childbirth, and supportive systems.

Let’s focus on what matters: building a society where families can thrive. If we do that, everything else—including birth rates—may just follow.

Love, YLE

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. Dr. Jetelina is also a senior scientific consultant to a number of non-profit organizations. YLE reaches over 340,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade.

Spread the word