The startling success of UKIP in recent by-elections raises all kinds of questions, for observers and participants from across the political spectrum. Is it a new phenomenon or a very old one in a new guise? To what extent does it pose a threat to Labour or does it only really impact on the Tories? Why are people attracted to a party with a demonstrably nonsensical programme, and does it matter that they are? Is there no way of decoupling working-class popular sentiment from xenophobia and racism?

Types of Populism

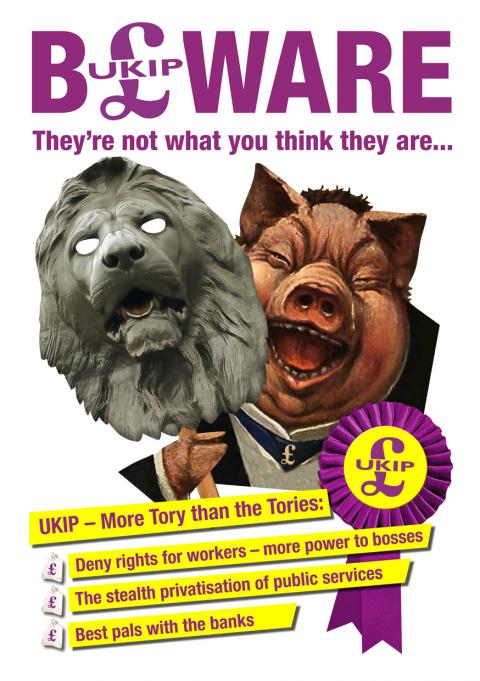

In many ways, UKIP is an easily recognisable phenomenon, exhibiting features which are typical of populist movements throughout history. Inchoate programmes, idiosyncratic, charismatic leaders, appeals to an assumed shared identity (in this case, beery white Englishness) against a largely imaginary external enemy (‘Europe’, ‘immigrants’); these have been the characteristic features of agrarian, urban and suburban populisms since ancient times.

This observation perhaps requires us to make a clear distinction between right-wing populism and left-populism. The former, while it may vary greatly between contexts, always appeals, at least in part, to a combination of xenophobia, authoritarianism, social conservatism and hostility to most forms of egalitarian collectivism. The latter, while similarly variable, will on some level always seek to identify the rich as the enemies of everyone else’s prosperity and happiness. It perhaps hardly needs saying that in a society as distorted by inequalities of wealth as our own, no democratic project can remain remotely convincing without a left-populist dimension.

It is instructive to reflect upon the differing modalities of left- and right- populism in mainstream British politics today. Both Cameron and Miliband do make occasional populist gestures, but they are always notable for either their weakness or their extremely short-lived character. But we are not looking at precisely parallel situations here. Cameron is acutely aware of just how ugly any form of right-wing populism appears to most constituencies outside of the very specific enclaves in which UKIP is currently making headway. His entire pitch to the Tories when he was elected their leader was predicated on the promise that he was too nice and too posh for there ever to be any danger of him going down that road; enabling him, they hoped, to ‘detoxify the brand’.

Miliband, on the other hand, makes more frequent and explicit efforts at mild populism, denouncing capitalist ‘predators’ and greedy energy providers in terms which no Labour leader would have dared since the end of the 1980s. His continued unpopularity stems not from the left-populist content of such pronouncements, but from the fact that he is so unconvincing when making them. He is hardly a social outsider, and the public are not fooled by his clumsy claims to represent anything but the more progressive wing of the same Oxbridge-Westminster-Media elite that produced Cameron. If Miliband could find a way to be more honest about that, and about a social system that, in 2014, can only offer us a choice between two straight white men who both read PPE and worked in TV for a while in between stints as special advisers, then he might not look so awkward when trying to play the tribune of the people. Indeed, under such circumstances, and with a bit more honesty from its leaders, a left populism ought to be much easier to prosecute and popularise than a right-wing populism. But is the UKIP surge proving this assumption wrong?

Does UKIP matter?

Not exactly. When UKIP came within 700 votes of taking a safe Labour seat in Heywood and Middleton, I for one was shocked. The following morning I was pronouncing to friends that I had clearly been wrong to be sceptical, earlier in the year, about claims that UKIP posed a major problem for Labour. But after a morning of intense Facebook-facilitated discussion with Alan Finlayson, Chris Brooke and others, I had recovered my composure.

Even in Heywood and Middleton, as Brooke was the first to point out to me, the statistics don’t provide much evidence of voters deserting Labour for UKIP (it looks more like a lot of Labour voters stayed home, because the polls were showing an easy Labour win, and a lot of Tories voted UKIP). The most recent national analysis finds Labour seats to be vulnerable to UKIP only in a handful of constituencies characterised by an atypical (for English Labour constituencies) level of ethnic homogeneity.

A key point to remember here is that there has always, since the 19th century, been a sizeable working class constituency for right-wing populism, and its adherents have never voted Labour. Labour has never commanded close to universal working class support, and has never been able to govern without the support of both the cosmopolitan cities and their aspirational suburbs. Despite this, there is almost an established convention amongst the mainstream British commentariat that working-class conservatism must be treated as some new phenomenon every time it is noticed, and that Labour must be obliged to appease it if it is to have a hope of governing. This ahistorical response serves a predictable ideological agenda, steering Labour leaderships away from any temptation to embrace a genuinely progressive populism. But all the evidence suggests that the success of UKIP represents not the emergence of some new tendency amongst Labour-voters, but rather the final withdrawal of support for the Conservative party by this historic strand of right-wing populism.

If this is what is happening, then it is clearly of great historic significance. Or is it? The recruitment of this historic strand of populist conservatism to the cause of neoliberalism was one of the key conditions of possibility for the latter’s implementation. This was a big part of the story told in that classic of political cultural studies, Hall et al’s Policing the Crisis (1978), which so brilliantly identified the moral panic around ‘mugging’ in the 1970s as part of the process leading from the emergence of Powellism in the 60s, to the hegemony of Thatcherism in the 80s. The politics of the ‘Third Way’ embraced by Clinton, Blair, Schroeder et. al. in the 1990s on the other hand, was as much as anything about finding a form of neoliberalism which was no longer dependent upon this conservative strand, but was instead acceptable to its more natural long-term allies among populations committed to social liberalism and cosmopolitan consumerism.

In the UK, this left the conservative, right-populist current either reluctantly voting Tory, or in large numbers not voting at all, as the Tories themselves realised how large a section of their own historic constituency had been won over to the same liberal, cosmopolitan, hedonistic values which were the basis for New Labour’s popular appeal. As such, the smooth functioning of the neoliberal project has not required support from this right-populist current for almost two decades now, and throughout that time the latter has remained a largely inactive, defensive element of British political culture. If it is now emerging finally as a coherent political force, does this really matter, given that it is likely to remain a marginal and increasingly residual one?

Well, clearly it matters to the Tories, who in their worst-case scenario stand to lose almost half of their historic base. To Labour it presents a number of overlapping challenges. Above all, it should serve as a powerful reminder of Labour’s own lost voters, the millions from historically left-leaning social groups (in particular young workers and the multicultural urban poor) who have stopped voting for the party or anyone else since 1997, and of the colossal missed opportunity presented by the failure to prosecute a genuinely left-populist project in the wake of the 2008 crash, when public antipathy to the power of finance capital was at historic levels.

Arguably given the balance of forces at that precise moment, Gordon Brown’s government actually had little choice but to prop up finance capital in its hegemonic role. In all likelihood, given the weakness of organised labour and wider progressive forces at that moment, a full-blown hegemonic crisis (which is what would have been provoked if the government had really turned on the bankers) would have opened the door for a more severe turn to the right than we have actually experienced. Which is why, in fact, these two questions for Labour resolve into one: How could the party mobilise the lost supporters who should be the natural constituents of its left flank, so as to ensure that next time the Left might actually be in a position to take advantage of a capitalist crisis (presuming it wanted to do that, which is a big presumption…)?

Left Populism in the UK?

Well, in the first place – and this sounds almost embarrassingly obvious, but I’ll say it anyway – it would have to take an explicitly anti-capitalist stance. I don’t mean anti-business. Commerce is not the same thing as capitalism. There is no contradiction between supporting the innovative, productive, and creative networks of small and medium-sized businesses which are so crucial to the dynamism of contemporary economies, and stating categorically that those institutions committed to the overriding goal of unlimited capital accumulation (banks, hedge funds, global corporations, etc.) should and could be abolished as soon as possible. The few useful functions of such institutions – providing large-scale infrastructure, channelling investment into productive areas – could easily be taken over by public bodies.

Of course nobody expects Miliband et al to take this position for the foreseeable future and it may be that in fact the best hope for the wider Left is to find some other vehicle through which a constituency could be mobilised. The great lesson of the Scottish independence campaign, although this has barely begun to sink in with the English left, is that the youth and the council estates can be mobilised under the right conditions, and this can result in the full emergence of an electoral force to Labour’s left, forcing major concessions and posing a real threat at the level of legislative elections. Nobody yet knows what the effect will be in Westminster if the SNP take 20+ Labour seats next May. But this is very likely to happen and there can be little doubt that if it does, ripples will be felt across the UK. Under such circumstances, it may well be that popularising the Green Party turns out to be the best medium-term strategy for mobilising that constituency south of the border.

But would it really be impossible for the Labour Party to take as strong a line as, say, Roosevelt in the 1930s, in stating categorically that it is the greed and overweening power of those institutions that is the source of most social problems today? Is it unimaginable that they would have the nous and the courage to point out that excessive capitalist power is the source of almost all such problems, including the problems faced by most businesses, and by those competing with immigrants in local labour markets? Is it too much to expect that they might finally acknowledge that under such circumstances, the key role for any democratic government is primarily to curtail and create effective counterweights to that profit-seeking power?

Such an assertion would surely be the best, indeed the only effective, way of meeting head-on those widespread misconceptions about the social effects of immigration and welfare which are the basis for UKIP’s appeal. Clearly at this precise historic juncture, widespread belief in these myths does threaten to expand support for right-populism beyond its traditional, residual base. The polling evidence is irrefutable that (a) lots of people are very worried about ‘immigration’ and about the supposedly parasitic behaviour of welfare claimants and (b) these fears are based on demonstrably misinformed views as to the number and nature of both immigrants and claimants, and can be effectively assuaged by exposure to accurate information,.

Given how widely publicised the research demonstrating these facts has been among the middle class intelligentsia, it seems at first glance perplexing that neither of the main parties has made much effort to disseminate its findings. The explanation for this is surely that they have not done so, because to do so in a rhetorically effective or logical way would require them to supply a coherent alternative explanation for the forms of suffering which citizens currently tend to blame on immigrants and claimant. The only such explanation that could command any plausibility would be one focusing on the effects of corporate greed. The Tories are obviously not going to go down that route. Labour, it seems are still terrified of doing so.

Popular Cosmopolitanism?

This probably explains why Labour have made no real attempt to activate that other great potential ideological resource in the war against UKIP’s xenophobia and victim-blaming: the considerable latent reserves of authentic cosmopolitanism in everyday popular culture. What we might call ‘popular cosmopolitanism’ is clearly a very widespread element of contemporary structures of feeling. It is actively present in every neighbourhood where people from different ethnic backgrounds or different countries of birth get along as good neighbours, and is part of the everyday experience of all people who enjoy, rather than simply resent, the experience of cultural multiplicity which living in almost every part of the UK affords today. It is there in the popularity of hybrid musical forms and of forms of speech or dress that can trace influences from around the globe. It is there in the casual resistance of most British people to anything that smacks of actual racism, and it is the common-sense of what Sunder Katwala rightly calls ‘the pro-migrant majority’. Why not simply appeal to this, and to the much older and well-established traditions of tolerance and liberal fair-play in order to counter the lazy, xenophobic insinuations of Farage and his colleagues?

The reason is that to do so would imply doing two other things that the Labour leadership still doesn’t want to do. Firstly, as I just suggested, it would involve supplying an alternative explanation for the relationship between immigration and falling levels of real wage to that proffered by UKIP, which would necessitate an explicit critique of the power of speculative capital. In fact Labour’s key response to the immigration issue in recent years has been to promise to tackle ‘unscrupulous’ employers who deliberately undercut local wage levels by importing cheap labour. But, like its moralistic attacks on payday lenders and promises of a short term freeze on energy bills, this has very limited appeal with a public who can sense very clearly, if only intuitively, that such measures are promising remedial action in response to a far more fundamental problem which they pointedly fail to address.

Democratic Populism and Democratic Deficit

The other issue which the Labour leadership still doesn’t want to take on is one which Katwala points to quite clearly. This is the fact that hostility to immigration is bound up as much as anything in contemporary Britain with the sense that rapid cultural change has been visited upon local communities without their having any say in whether or how that change would occur. This is a crucial issue, because it is in this sense above all others that ‘immigration’ has become for many British citizens a kind of metonym for the entire experience of democratic disenfranchisement. The truth is that nobody in this country voted for neoliberalism, Both Tory and Labour governments have been elected largely by voters who believed themselves to be voting for something quite different from what they got, be it a restoration of ‘traditional’ family values and social order or a resumption of the post-war social democratic project. Mass immigration, and declining real wages are together the most visible and tangible symptoms of the deregulation of labour markets, which along with privatisation and low tax rates is one of the key core objectives of all neoliberal policy. But Labour would rather promise to curtail immigration and (almost entirely mythical) ‘welfare tourism’ , lending almost complete credibility to the UKIP narrative, than admit to its own historic complicity with a political programme that has never enjoyed a popular mandate.

For this would surely have to be a crucial element of any populist narrative which could effectively confront the UKIP story, as seductive as it is, with its promise of restored democracy and restored popular sovereignty if only we leave the EU. Such a narrative would have to possess a radical democratic dimension, acknowledging not just the short-term unpopularity of existing democratic arrangements, but their complete unfitness for the purposes of enabling a highly complex, fluid, and diverse contemporary society effectively to govern itself.

This, in fact, is the central theme of the pamphlet authored by myself and Mark Fisher and published by Compass. In the pamphlet, we argue that there is simply no way of addressing the various popular desires which neoliberalism is so evidently failing to fulfil without a radical programme of democratic reform which would extend participation and collective decision-making across much of the public and indeed the private sectors. Only if publics are genuinely enabled to engage in meaningful, ongoing, open-ended collective decision-making in a range of spheres can the justifiable sense that things are being done to them by people they did not authorise to do them actually be assuaged. It is a cliché of British political discourse to suggest that any concern with democratic reform is an exclusive preserve of the educated elite, distant from the concerns of the wider populace. What has happened in Scotland has completely blown this claim out of the water, demonstrating that in fact the reverse is true: if genuine and dramatic democratic reform is on offer, then this is of great interest especially to the most marginalised and disenfranchised populations.

That popular ‘disillusionment’ with formal politics which is currently driving so many voters into the arms of UKIP is not some kind of facile error. Such voters are entirely correct to have jettisoned any illusions they may have retained about the capacity of established institutions to represent their interests. If the only section of the disillusioned public to have found a substantial voice is that with a historic affinity with right-populism, this does not mean that the same sense of disillusion and clear-eye disaffection is not far more widely distributed, especially among the young and the poor. The only effective response from the Left, even the Centre-Left, can be one which is honest about the enormous problems caused by the excessive power and greed of finance capital, and which offers a so-far unprecedented programme of radical democratic reform. This is not the politics of utopia: it is the only meaningful response possible to the likely collapse of Labour’ s vote in Scotland in 2016, and the striking emergence of UKIP as a fifth force (alongside Labour, Conservatives, Liberal Democrats and Greens) in English politics.

Spread the word