There is no "but" about what happened at Charlie Hebdo yesterday. Some people published some cartoons, and some other people killed them for it. Words and pictures can be beautiful or vile, pleasing or enraging, inspiring or offensive; but they exist on a different plane from physical violence, whether you want to call that plane spirit or imagination or culture, and to meet them with violence is an offense against the spirit and imagination and culture that distinguish humans. Nothing mitigates this monstrosity. There will be time to analyze why the killers did it, time to parse their backgrounds, their ideologies, their beliefs, time for sociologists and psychologists to add to understanding. There will be explanations, and the explanations will be important, but explanations aren't the same as excuses. Words don't kill, they must not be met by killing, and they will not make the killers' culpability go away.

To abhor what was done to the victims, though, is not the same as to become them. This is true on the simplest level: I cannot occupy someone else's selfhood, share someone else's death. This is also true on a moral level: I cannot appropriate the dangers they faced or the suffering they underwent, I cannot colonize their experience, and it is arrogant to make out that I can. It wouldn't be necessary to say this, except the flood of hashtags and avatars and social-media posturing proclaiming #JeSuisCharlie overwhelms distinctions and elides the point. "We must all try to be Charlie, not just today but every day," the New Yorker pontificates. What the hell does that mean? In real life, solidarity takes many forms, almost all of them hard. This kind of low-cost, risk-free, E-Z solidarity is only possible in a social-media age, where you can strike a pose and somebody sees it on their timeline for 15 seconds and then they move on and it's forgotten except for the feeling of accomplishment it gave you. Solidarity is hard because it isn't about imaginary identifications, it's about struggling across the canyon of not being someone else: it's about recognizing, for instance, that somebody died because they were different from you, in what they did or believed or were or wore, not because they were the same. If people who are feeling concrete loss or abstract shock or indignation take comfort in proclaiming a oneness that seems to fill the void, then it serves an emotional end. But these Cartesian credos on Facebook and Twitter - I am Charlie, therefore I am - shouldn't be mistaken for political acts.

Among the dead at Charlie Hebdo: Deputy chief editor Bernard Maris and cartoonists Georges Wolinski, Jean Cabut (aka Cabu), Stephane Charbonnier, who was also editor-in-chief, and Bernard Verlhac (aka Tignous)

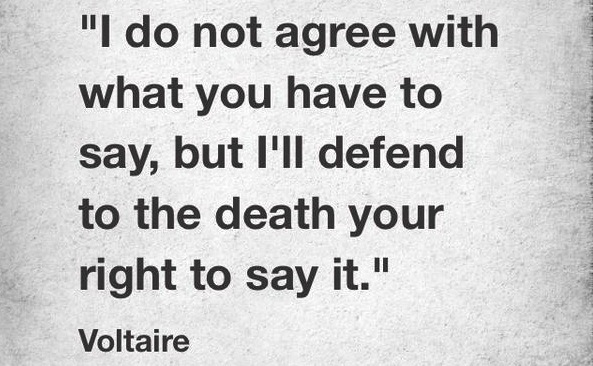

Erasing differences that actually exist seems to be the purpose here: and it's perhaps appropriate to the Charlie cartoons, which drew their force from a considered contempt for people with the temerity to be different. For the last 36 hours, everybody's been quoting Voltaire. The same line is all over my several timelines:

From the twitter feed of @thereaIbanksy, January 7

"Those 21 words circling the globe speak louder than gunfire and represent every pen being wielded by an outstretched arm," an Australian news site says. (Never mind that Voltaire never wrote them; one of his biographers did.) But most people who mouth them don't mean them. Instead, they're subtly altering the Voltairean clarion cry: the message today is, I have to agree with what you say, in order to defend it. Why else the insistence that condemning the killings isn't enough? No: we all have to endorse the cartoons, and not just that, but republish them ourselves. Thus Index on Censorship, a journal that used to oppose censorship but now is in the business of telling people what they can and cannot say, called for all newspapers to reprint the drawings: "We believe that only through solidarity - in showing that we truly defend all those who exercise their right to speak freely - can we defeat those who would use violence to silence free speech." But is repeating you the same as defending you? And is it really "solidarity" when, instead of engaging across our differences, I just mindlessly parrot what you say?

But no, if you don't copy the cartoons, you're colluding with the killers, you're a coward. Thus the right-wing Daily Caller posted a list of craven media minions of jihad who oppose free speech by not doing as they're ordered. Punish these censors, till they say what we tell them to!

If you don't agree with what Charlie Hebdo said, the terrorists win.

You're not just kowtowing to terrorists with your silence. According to Tarek Fatah, a Canadian columnist with an evident fascist streak, silence is terrorism.

Of course, any Muslim in the West would know that being called "our enemy" is a direct threat; you've drawn the go-to-GItmo card. But consider: This idiot thinks he is defending free speech. How? By telling people exactly what they have to say, and menacing the holdouts with treason. The Ministry of Truth has a new office in Toronto.

There's a perfectly good reason not to republish the cartoons that has nothing to do with cowardice or caution. I refuse to post them because I think they're racist and offensive. I can support your right to publish something, and still condemn what you publish. I can defend what you say, and still say it's wrong - isn't that the point of the quote (that wasn't) from Voltaire? I can hold that governments shouldn't imprison Holocaust deniers, but that doesn't oblige me to deny the Holocaust myself.

It's true, as Salman Rushdie says, that "Nobody has the right to not be offended." You should not get to invoke the law to censor or shut down speech just because it insults you or strikes at your pet convictions. You certainly don't get to kill because you heard something you don't like. Yet, manhandled by these moments of mass outrage, this truism also morphs into a different kind of claim: That nobody has the right to be offended at all.

I am offended when those already oppressed in a society are deliberately insulted. I don't want to participate. This crime in Paris does not suspend my political or ethical judgment, or persuade me that scatologically smearing a marginal minority's identity and beliefs is a reasonable thing to do. Yet this means rejecting the only authorized reaction to the atrocity. Oddly, this peer pressure seems to gear up exclusively where Islam's involved. When a racist bombed a chapter of a US civil rights organization this week, the media didn't insist I give to the NAACP in solidarity. When a rabid Islamophobic rightist killed 77 Norwegians in 2011, most of them at a political party's youth camp, I didn't notice many #IAmNorway hashtags, or impassioned calls to join the Norwegian Labor Party. But Islam is there for us, it unites us against Islam. Only cowards or traitors turn down membership in the Charlie club.The demand to join, endorse, agree is all about crowding us into a herd where no one is permitted to cavil or condemn: an indifferent mob, where differing from one another is Thoughtcrime, while indifference to the pain of others beyond the pale is compulsory.

We've heard a lot about satire in the last couple of days. We've heard that satire shouldn't cause offense because it's a weapon of the weak: "Satire-writers always point out the foibles and fables of those higher up the food chain." And we've heard that if the satire aims at everybody, those forays into racism, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism can be excused away. Charlie Hebdo "has been a continual celebration of the freedom to make fun of everyone and everything..it practiced a freewheeling, dyspeptic satire without clear ideological lines." Of course, satire that attacks any and all targets is by definition not just targeting the top of the food chain. "The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges," Anatole France wrote; satire that wounds both the powerful and the weak does so with different effect. Saying the President of the Republic is a randy satyr is not the same as accusing nameless Muslim immigrants of bestiality. What merely annoys the one may deepen the other's systematic oppression. To defend satire because it's indiscriminate is to admit that it discriminates against the defenseless.

Funny little man: Contemporary Danish cartoon of Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard, the greatest satirist of his century, famously recounted his dream: "I was rapt into the Seventh Heaven. There sat all the gods assembled." They granted him one wish: "Most honorable contemporaries, I choose one thing - that I may always have the laughter on my side." Kierkegaard knew what he meant: Children used to laugh and throw stones at him on Copenhagen streets, for his gangling gait and monkey torso. His table-turning fantasy is the truth about satire. It's an exercise in power. It claims superiority, it aspires to win, and hence it always looms over the weak, in judgment. If it attacks the powerful, that's because there is appetite underneath its asperity: it wants what they have. As Adorno wrote: "He who has laughter on his side has no need of proof. Historically, therefore, satire has for thousands of years, up to Voltaire's age, preferred to side with the stronger party which could be relied on: with authority." Irony, he added, "never entirely divested itself of its authoritarian inheritance, its unrebellious malice."

Satire allies with the self-evident, the Idées reçues, the armory of the strong. It puts itself on the team of the juggernaut future against the endangered past, the successful opinion over the superseded one. Satire has always fed on distaste for minorities, marginal peoples, traditional or fading ways of life. Adorno said: "All satire is blind to the forces liberated by decay."

Funny little man: Voltaire writing

Charlie Hebdo, the New Yorker now claims, "followed in the tradition of Voltaire." Voltaire stands as the god of satire; any godless Frenchman with a bon mot is measured against him. Everyone remembers his diatribes against the power of the Catholic Church: Écrasez l'Infâme! But what's often conveniently omitted amid the adulation of his wit is how Voltaire loathed a powerless religion, the outsiders of his own era, the "medieval," "barbaric" immigrant minority that afflicted Europe: the Jews.

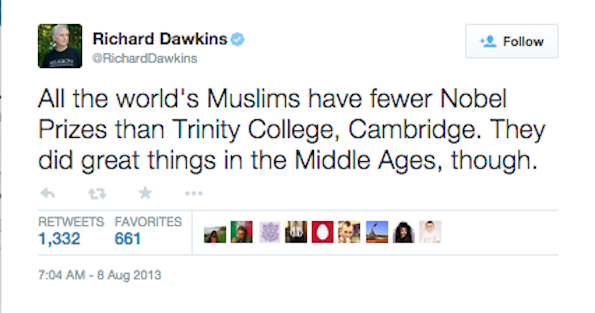

Voltaire's anti-Semitism was comprehensive. In its contempt for the putatively "primitive," it anticipates much that is said about Muslims in Europe and the US today. "The Jews never were natural philosophers, nor geometricians, nor astronomers," Voltaire declared. That would do head Islamophobe Richard Dawkins proud:

The Jews, Voltaire wrote, are "only an ignorant and barbarous people, who have long united the most sordid avarice with the most detestable superstition and the most invincible hatred for every people by whom they are tolerated and enriched." When some American right-wing yahoo calls Muslims "goatfuckers," you might think he's reciting old Appalachian invective. In fact, he's repeating Voltaire's jokes about the Jews. "You assert that your mothers had no commerce with he-goats, nor your fathers with she-goats," Voltaire demanded of them. "But pray, gentlemen, why are you the only people upon earth whose laws have forbidden such commerce? Would any legislator ever have thought of promulgating this extraordinary law if the offence had not been common?"

Nobody wishes Voltaire had been killed for his slanders. If some indignant Jew or Muslim (he didn't care for the "Mohammedans" much either) had murdered him mid-career, the whole world would lament the abomination. In his most Judeophobic passages, I can take pleasure in his scalpel phrasing - though even 250 years after, some might find this hard. Still, liking the style doesn't mean I swallow the message. #JeSuisPasVoltaire. Most of the man's admirers avoid or veil his anti-Semitism. They know that while his contempt amuses when directed at the potent and impervious Pope, it turns dark and sour when defaming a weak and despised community. Satire can sometimes liberate us, but it is not immune from our prejudices or untainted by our hatreds. It shouldn't douse our critical capacities; calling something "satire" doesn't exempt it from judgment. The superiority the satirist claims over the helpless can be both smug and sinister. Last year a former Charlie Hebdo writer, accusing the editors of indulging racism, warned that "The conviction of being a superior being, empowered to look down on ordinary mortals from on high, is the surest way to sabotage your own intellectual defenses."

You are an infamous impostor, Father, but at least you're circumcised: Voltaire lectures to a priest

Of course, Voltaire didn't realize that his Jewish victims were weak or powerless. Already, in the 18th century, he saw them as tentacles of a financial conspiracy; his propensity for overspending and getting hopelessly in debt to Jewish moneylenders did a great deal to shape his anti-Semitism. In the same way, Charlie Hebdo and its like never treated Muslim immigrants as individuals, but as agents of some larger force. They weren't strivers doing the best they could in an unfriendly country, but shorthand for mass religious ignorance, or tribal terrorist fanaticism, or obscene oil wealth. Satire subsumes the human person in an inhuman generalization. The Muslim isn't just a Muslim, but a symbol of Islam.

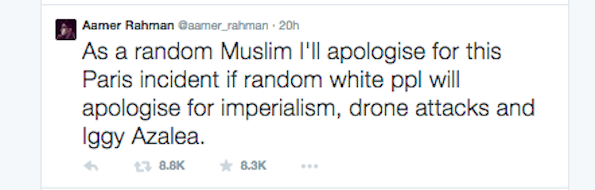

This is where political Islamists and Islamophobes unite. They cling to agglutinative ideologies; they melt people into a mass; they erase individuals' attributes and aspirations under a totalizing vision of what identity means. A Muslim is his religion. You can hold every Muslim responsible for what any Muslim does. (And one Danish cartoonist makes all Danes guilty.) So all Muslims have to post #JeSuisCharlie obsessively as penance, or apologize for what all the other billion are up to. Yesterday Aamer Rahman, an Australian comic and social critic, tweeted:

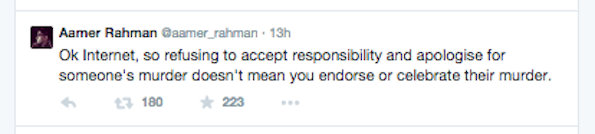

A few hours later he had to add:

This insistence on contagious responsibility, collective guilt, is the flip side of #JeSuisCharlie. It's #VousEtesISIS; #VousEtesAlQaeda. Our solidarity, our ability to melt into a warm mindless oneness and feel we're doing something, is contingent on your involuntary solidarity, your losing who you claim to be in a menacing mass. We can't stand together here unless we imagine you together over there in enmity. The antagonists are fake but they're entangled, inevitable. The language hardens. Geert Wilders, the racist right-wing leader in the Netherlands, said the shootings mean it's time to "de-Islamize our country." Nigel Farage, his counterpart in the UK, called Muslims a "fifth column, holding our passports, that hate us." Juan Cole writes that the Charlie Hebdo attack was "a strategic strike, aiming at polarizing the French and European public" - at "sharpening the contradictions." The knives are sharpening too, on both sides.

We lose our ability to imagine political solutions when we stop thinking critically, when we let emotional identifications sweep us into factitious substitutes for solidarity and action. We lose our ability to respond to atrocity when we start seeing people not as individuals, but as symbols. Changing avatars on social media is a pathetic distraction from changing realities in society. To combat violence you must look unflinchingly at the concrete inequities and practices that breed it. You won't stop it with acts of self-styled courage on your computer screen that neither risk nor alter anything. To protect expression that's endangered you have to engage with the substance of what was said, not deny it. That means attempting dialogue with those who peacefully condemn or disagree, not trying to shame them into silence. Nothing is quick, nothing is easy. No solidarity is secure. I support free speech. I oppose all censors. I abhor the killings. I mourn the dead. I am not Charlie.

[Scott Long was born in southwestern Virginia in the U.S., to parents who started as Midwestern liberals (from Ohio, specifically), but moved South at the beck of their professions at the Fifties' sagging end. (My father was an extension agent at Virginia Tech, my mother an elementary school teacher and principal.) My childhood happened during the turmoil of desegregation and the civil rights movement. These impinged on me only distantly, through the convex moon of the TV screen, but also through my parents' quiet reaction. Their moral refusal, especially my mother's, to submit to the racial and cultural attitudes of the region where they found themselves living was a retrospective example, and gave me a sense of displacement that has lasted ever since.

For almost seven years after the revolutions of '89, I lived in Eastern Europe - for more than four years in Hungary, where I taught literature at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest. For two years in the middle, I was a senior Fulbright professor at Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj, Romania.

In devastated Romania, I started doing human rights work. It happened quite unexpectedly, almost without my knowing that was what it was. Together with a few Romanian friends, in the weeks after I first moved there I started visiting prisons, documenting and defending people imprisoned under the country's Ceau?escu-era sodomy law. We had very little idea of human rights law, norms, precedents, or standards; we were, in a sense, making it up as we went along. We produced some of the first human rights information ever about abuses based on sexual orientation. We were responsible for Amnesty International taking up one of its first gay cases as a prisoner of conscience, and helped bring about Human Rights Watch's policy change to act against such violations. (see more here.]

Spread the word