One of the simple facts of the economy that troubles many economists is the absence of any relationship between profits and investment. Economists like to tell people that if we make investment more profitable, we will have more investment. It turns out the world doesn't work that way.

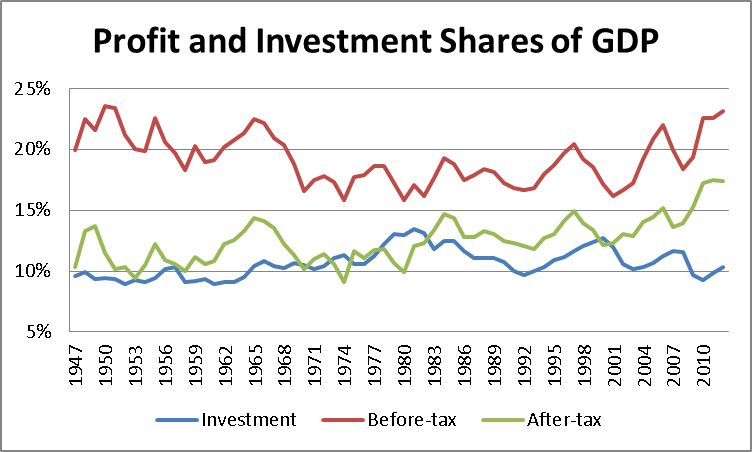

Here's one of my favorite graphs of the economy going back to the early years right after World War II. It's about as simple as it gets. It shows the investment share of GDP. Then it shows the profit share of net value added in the corporate sector. The measure of profit here is the broad measure of business operating surplus. Using net takes away the downward bias in recent years that would result from a rising depreciation share of output. The last line is the after-tax profit share.

The first item worth noting here is that investment doesn't fluctuate all that much. It peaks at 13.4 percent of GDP in 1981. The closest it ever comes to this share again is in the looniness of the stock bubble when the ability to raise money on Wall Street for every crazy idea pushed the investment share up to 12.7 percent of GDP. Even this number is overstated by 0.3-0.4 percentage points because of the growth of car leasing in the 1990s. (A leased car is owned by the leasing company and therefore counts as investment. By contrast, when a consumer buys a car it is treated as consumption.)

The takeaway is that anyone who expects a huge uptick in investment to provide a major boost to demand is either smoking something serious or simply has never looked at the data. It hasn't happen in the last 65 years and it's not about to happen now.

But the other part of the story that provides great fun and amusement is the seeming inverse relationship between profits and investment. Note that the investment share is at its highest in the late 1970s and early 1980s when the profit share (both before and after-tax) is at its lowest. The profit share, especially the after-tax share, rises in the 1980s as the investment share falls. Then we have a further rise in the last five years and the investment share falls again.

Why isn't a higher return to capital associated with more investment? Well if there is a substantial amount of monopoly power in the economy then it would not be surprising that we don't see more profits leading to more investment. In that case the high profits are a direct result of restricting supply. The last thing a company wants to do in this context is produce more output, which would then push down its profit margins.

Apple is the quintessential example of such a company. It's a hugely profitable company that can't think of anything to do with its profits. Recently it has been giving more of them back to shareholders in dividends.

Unfortunately the Apple story is not unique. We have many industries where the leading firms are drowning in profits for which they have no use.

If investment is driven by demand this can actually lead to the perverse situation we see in the graph. The more money that goes to firms in profits the less goes to workers in wages. If workers spend their wages, in contrast to companies hoarding profits, then we see less demand growth as the profit share rises.

I won't say that this is necessarily the story behind the picture in the graph, but it certainly fits better than a story that has investment increasing in response to a rise in profits.

Spread the word