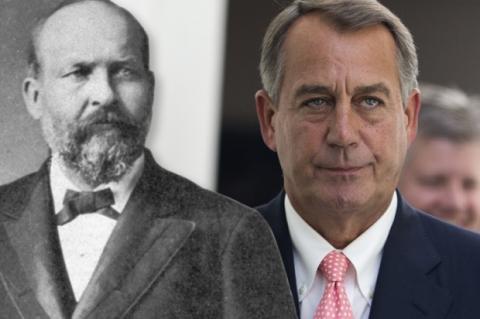

Today’s shutdown crisis has an eerily familiar predecessor. It echoes America’s first battle over a government shutdown, which came not in the 20th century, but rather, shortly after the Civil War. In 1879, ex-Confederates in Congress, desperate to turn the direction of the nation, refused to fund the government unless the Republican president promised to abandon his party and do things their way. Republicans then saw the situation for what it was. “If this is not revolution,” House Minority Leader James Garfield concluded, “which if persisted in will destroy the government, I am wholly wrong in my conception of both the word and the thing.”

Garfield knew exactly what revolution meant. He had fought to protect his government from revolutionaries at the Battle of Shiloh, where more than 13,000 Union soldiers fell, and at Chickamauga, which took another 16,000. Only 14 years later, the very same men who had made war against the government on the battlefield were making war against it from their congressional seats.

On its face, the crisis was over the presence of the handful of troops still stationed in the South, there to try to enforce the equality that Union soldiers had died to guarantee. Southern Democrats hated federal protection of black voting, but Democrats’ minority in the government made them powerless to stop it until a bad recession prompted voters to give their party control of Congress for the first time since the Civil War. Ignoring the economic crisis, a cabal of Southern ex-Confederates in the Democratic Party immediately set out to reverse the course the country had taken since they had seceded 18 years before. Determined to override the new nationalism and make states’ rights the law of the land, they forced a weak Democratic speaker of the House to attach riders to a routine appropriations bill, making it a crime to enforce black voting.

Southern Democrats were not shy about what they were doing. Democratic congressmen extolled the virtues of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and celebrated the former Confederates who had been elected to make up their new majority. Just like Davis, they claimed, all they asked was to be left alone to run their states as they wished. One ex-Confederate told the New York Times that leaving Congress in 1861 had been a great blunder. Southerners were far more likely to win their goals by controlling Congress. Southern Democrats urged their constituents to “present a solid front to the enemy.”

Republicans and moderate Democrats recognized the riders as a new front in white Southerners’ war to force the government to bow to their demands. Having lost on the battlefields, they would coerce the president to give in to them or they would starve the government to death. This was precisely how Confederates had operated in the past. After all, Confederates began the war when they fired on relief ships trying to resupply Fort Sumter, and Confederates had starved Union soldiers to death at Andersonville prison camp. In 1879, a popular cartoon showed a skeletal soldier in an army with “no appropriations” talking with “Uncle Sam.”

“Uncle,” said the skeleton, “this reminds me of Andersonville.” “’HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF’—A LITTLE TOO SOON,” agreed the cartoon’s caption.

The riders were about troops and voting, but at issue was the very structure of American government. President Hayes and Minority leader Garfield recognized that if an extremist faction in Congress could force its will on the country by holding government finances hostage, it would erase the power of the president and destroy the basic structure of the American government’s separation of powers. Even moderate Democrats, who didn’t particularly like the idea of troops enforcing black rights, agreed that the threat was truly revolutionary and menaced the Constitution. If the extremists’ tactics worked, this would be only the first of their demands, and the country would fall, as one Democrat said, under “the absolute despotism of an irresponsible and unrestrained partisan majority” in Congress.

Five times, Hayes vetoed the bill with the riders and, as popular opinion swung behind him, the Democrats backed down. In the short term, caving to the extremists destroyed the Democrats in the upcoming election, when Republicans reversed their recent losses and put Garfield, now famous for his stand against the riders, into the White House. In the longer term, the ultimate reluctance of ex-Confederates to force a constitutional crisis so soon after the Civil War meant that America never resolved the crucial question of what to do when a faction in Congress refuses to fund the government unless it gets its way.

With politics polarized much as it was in 1879, that omission is coming back to haunt us.

Heather Cox Richardson teaches nineteenth-century American history at Boston College.

Spread the word