Socialist Kshama Sawant’s election to the Seattle City Council in November 2013 made national news, a kind of “man bites dog” story that the media found shocking and irresistible. The Los Angeles Times’s front-page article described Sawant as “41-year-old software-engineer-turned-far-left-sweetheart.” The Seattle Times called her “the council’s first socialist member in modern history.”

In fact, the United States has a long tradition of municipal socialism. One hundred years ago, at the Socialist Party’s high point, about 1,200 party members held public office in 340 cities, including seventy‑nine mayors in cities such as Milwaukee, Buffalo, Minneapolis, Reading, and Schenectady. (Before Sawant, the last socialist to get elected in Seattle was journalist Anna Louise Strong, who won a seat on the School Board in 1916). These local leaders, whose ranks included working-class labor union members and middle-class radicals such as teachers, clergy, and lawyers, worked alongside progressive reformers to improve living and working conditions in the nation’s burgeoning cities. In today’s hyper-capitalist economy, their experience may still offer some lessons for contemporary activists.

Seattle political analysts are still trying to assess how Sawant—who beat sixteen-year incumbent Richard Conlin by a slim margin despite being outspent more than two to one—managed to pull off her remarkable upset. Her effective grassroots campaign and knack for proposing policy ideas that seemed both radical and reasonable played a key role. But Sawant’s victory is also a result of the growing unease—in Seattle and across the country—with widening inequality and the growing influence of big business in politics. Much of this was expressed by the Occupy Wall Street movement that began in September 2011, but while Occupy activists have generally eschewed electoral politics as a strategy for change, their message has continued to resonate with the American public, and many mainstream politicians and pundits have embraced the “1 percent vs. 99 percent” theme.

On the same day that Sawant won her city council seat, progressives and radicals around the country won a number of significant local victories. The most celebrated was Bill de Blasio’s landslide election to the New York City mayoralty on a platform challenging the city’s growing inequality and gentrification. Minneapolis voters elected City Council member Betsy Hodges—a longtime activist with the progressive grassroots group Take Action Minnesota who called on people to “free ourselves from the fear that keeps us locked into patterns of inequality”—as their new mayor. Another longtime Take Action Minnesota member, Dai Thao, became the first Hmong city council member in the St. Paul’s history. In Minneapolis, Ty Moore, an Occupy organizer and Socialist Alternative candidate, narrowly lost a contest for City Council. Meanwhile, Boston voters catapulted union leader and state legislator Martin Walsh into the mayor’s office, despite business-led efforts to lambast him as a radical.

One of Sawant’s key campaign platforms was a pledge to push for a $15-an-hour municipal minimum wage. This might have seemed outrageous a year ago, but on the same day Seattle voters elected Sawant, voters in the adjacent suburb of Seatac approved that same minimum wage for about 6,000 workers at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and airport-related businesses, including hotels, car-rental agencies, and parking lots. Both Seattle’s defeated incumbent mayor, Mike McGinn, and his successor Ed Murray endorsed the Seatac initiative and raised the possibility of doing the same thing in Washington’s largest city. (San Francisco, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque already have municipal minimum wages).

* * *

Neither Sawant’s affiliation with the small Trotskyist group Socialist Alternative—a branch of the British-based Committee for a Workers International—nor her immigrant background seem to have impeded her campaign. Sawant grew up in Mumbai, India, where she received a bachelor’s degree in computer science, and in 1994 moved to the United States with her husband, abandoning her career in computers for a Ph.D. in economics. She became a U.S. citizen in 2010 and teaches economics at Seattle Central Community College.

Sawant was well-known in Seattle’s activist community long before winning public office. After city officials removed Occupy protesters from Westlake Park, Sawant helped them find a friendlier, though temporary, home on the SCCC campus. She was also one of several Occupy activists arrested for blocking King County sheriff’s deputies from evicting a man from his home and a regular participant at protests led by striking fast-food workers and cab drivers. Her activism shaped her campaign platform. In addition to calling for a citywide minimum wage, Sawant also called for rent control to address Seattle’s skyrocketing housing costs, a millionaire’s tax to fund mass transit and education, and universal pre-school.

None of these pronouncements distinguish Sawant from what many other progressives have called for. But Sawant’s political program goes a step further, calling for what Michael Harrington once called the “left wing of the possible.” For example, in response to Boeing’s threat to move its airplane production operation out of Seattle unless it gets major concessions from the machinists union and large tax breaks from the state legislature, Sawant joined with union members who boldly rejected the company’s give-back demands. “We don’t need the executives!” she said at the union rally. “We need Boeing to be under democratic public ownership by workers—by the community.”

As the only socialist on the nine-member City Council, Sawant isn’t about to transform Seattle into a Pacific Northwest replica of Sweden. Indeed, it isn’t clear yet whether she has the patience, pragmatism, or political skill to successfully walk the tightrope of a being a radical in municipal government—of being an insider and an outsider at the same time. Her effectiveness will depend on her ability to work with Seattle’s progressives—unions, community organizing groups, environmentalists, and others—to mobilize support for a common agenda, and then to push her liberal colleagues on the City Council as well as newly-elected Mayor Murray, also a liberal, to embrace a bolder vision of urban progressivism.

* * *

Their grievances should sound familiar today: an increasing concentration of wealth, a widening gap between the rich and the poor, and the growing political influence of corporate power brokers then known as robber barons. Journalists investigated and publicized the problems of the poor, often encouraging fellow middle- and upper‑class Americans to join with working‑class activists through groups such as the Women’s Trade Union League, the National Consumers League, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, the National Child Labor Committee, and a growing network of settlement houses such as Chicago’s Hull House and New York’s Henry Street Settlement.

With votes from immigrants, workers, and a rising professional middle class, progressive reformers won elections in many cities. In Ohio, mayors Tom Johnson of Cleveland (1901–1909) as well as Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones and Brand Whitlock of Toledo (1897–1903 and 1906–1913, respectively) fought for fair taxes and better social services, and against high street car and utility rates. Reformers in Jersey City, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Detroit, Los Angeles, Bridgeport, and many other cities sought to tax wealthy property owners, create municipal electricity and water utilities, and hold down transit fares.

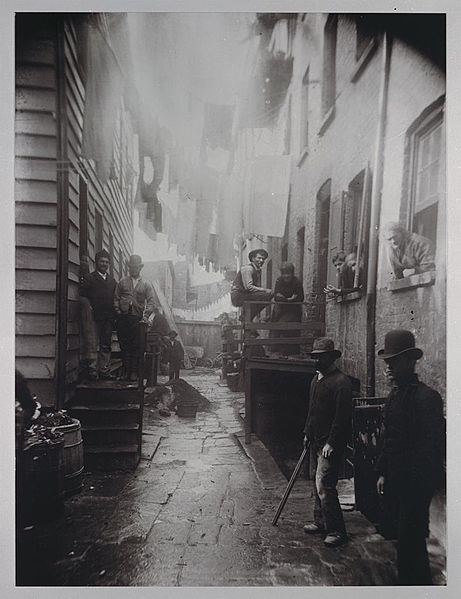

Like the urban political machines that dominated many big cities in the early 1900s, the progressives used municipal jobs to provide employment to immigrant and working-class voters. But unlike the corrupt machine politicians, progressives also took sides in the collective struggles of these constituents. A decade after muckraking journalist Jacob Riis published his 1890 classic, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, exposing the awful conditions in the city’s slums, middle-class reformers successfully pushed for state laws requiring fire escapes, windows in every room, interior bathrooms, and courtyards designed for garbage removal. During strikes, they stopped the local police from protecting strikebreaking “scabs.” After the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in New York in 1911—which killed 145 immigrant girls—upper-class feminists, middle-class reformers, immigrant-based garment workers, and radical socialists joined forces to enact tough factory safety laws, helped by allies like Robert Wagner and Al Smith in the state legislature.

Like the urban political machines that dominated many big cities in the early 1900s, the progressives used municipal jobs to provide employment to immigrant and working-class voters. But unlike the corrupt machine politicians, progressives also took sides in the collective struggles of these constituents. A decade after muckraking journalist Jacob Riis published his 1890 classic, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, exposing the awful conditions in the city’s slums, middle-class reformers successfully pushed for state laws requiring fire escapes, windows in every room, interior bathrooms, and courtyards designed for garbage removal. During strikes, they stopped the local police from protecting strikebreaking “scabs.” After the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in New York in 1911—which killed 145 immigrant girls—upper-class feminists, middle-class reformers, immigrant-based garment workers, and radical socialists joined forces to enact tough factory safety laws, helped by allies like Robert Wagner and Al Smith in the state legislature.

In Detroit, Hazen Pingree, the reform mayor from 1890 to 1897, mobilized working-class voters and pressured the City Council to create a municipal electrical utility and increase taxes on wealthy property owners, overcoming opposition from businesses and even his own Baptist church (which revoked his family pew). When employees of the Detroit City Railway Company went on strike in 1891, Pingree refused the company’s request to bring in the state militia to halt the strike. In his battle with the powerful private gas, telephone, and transit companies, Pingree encouraged customers not to pay their bills, successfully pressuring the companies to lower rates. After winning four terms as mayor of Detroit—initially by beating business-backed politicians by building a coalition of working-class Polish, Germans, and Irish immigrants as well as the middle class—Pingree served two terms as governor of Michigan, where he continued the fight for progressive reform.

* * *

Other socialists included muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens (who exposed municipal corruption in his articles in McClure’s magazine, collected in The Shame of the Cities), writer Upton Sinclair (whose 1906 novel The Jungle, about the harsh conditions among Chicago’s meatpacking workers, led to the enactment of the first consumer protection law, the Meat Inspection Act), and Lewis Hine, whose photographs exposed the brutal conditions of child labor to an outraged public. Two socialist newspapers—the Appeal to Reason (based in Kansas) and the Jewish Daily Forward (based in New York)—each reached at least a quarter of a million readers around the country. New York, Milwaukee, Chicago, and other cities had their own weekly socialist papers.

Although progressives and socialists had different goals—progressives wanted to humanize capitalism, while socialists viewed these reforms as steppingstones to a deeper social transformation—they joined forces effectively in the urban progressive movement. Socialists recognized that they could not bring socialism to one city, but they pushed for public ownership of utilities and transportation facilities; the expansion of parks, libraries, playgrounds, and other services; and a friendlier attitude toward unions, especially in time of strikes. Many socialists—including Job Harriman, who came close to being elected Los Angeles mayor in 1911—pushed for “living wage” laws. Their advocacy paved the way for state laws in the early 1900s and the adoption of the federal minimum wage in 1938.

Progressives and socialists earned reputations for clean and well-run local governments. Especially successful were their pioneering efforts to promote public health, including clean water, to help reduce dangerous diseases. In Milwaukee, where Socialists led the city government for several decades, this attention to good management and infrastructure earned them the label “sewer socialists.”

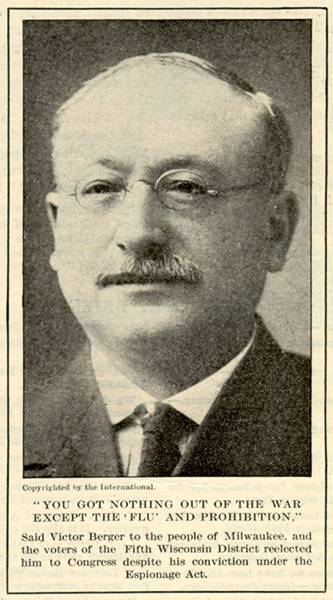

Indeed, Milwaukee was the socialist movement’s ground zero in the early 1900s. Dominated by the brewery industry, the city was home to many Polish, German, and other immigrant workers who made up the movement’s rank and file. In 1910 Milwaukee voters elected Emil Seidel, a former patternmaker, as their mayor, gave Socialists a majority of the seats on the city council and the county board, and selected Socialists for the school board and as city treasurer, city attorney, comptroller, and two civil judgeships. That year they also sent union leader and newspaper editor Victor Berger to Washington, making him one of two Socialists in Congress. (The other, Meyer London of New York, was elected in 1914).

In Congress, Berger sponsored bills providing for government ownership of the radio industry, abolition of child labor, self-government for the District of Columbia, and a system of public works for relief of the unemployed. He put forward resolutions for the withdrawal of federal troops from the Mexican border, the abolition of the Senate (which was then not yet elected directly by the voters and was called the “millionaires’ club”), women’s suffrage, and federal ownership of the railroads. Berger also sponsored the first bill to create “old age pensions.” It got little support at the time, but two decades later, during the Depression, FDR and his labor secretary, Francis Perkins—who had been a key force in the anti-sweatshop struggles in New York after the Triangle tragedy—persuaded Congress to enact Social Security.

In office, Milwaukee’s Socialists expanded the city’s parks and library system and improved the public schools. They paid city employees union-level wages and granted municipal employees an eight-hour day. They adopted tough factory and building regulations. They reined in police brutality against striking workers and improved working conditions for rank-and-file cops. They improved the harbor, built municipal housing, and sponsored public markets. The Socialists had their own newspaper and sponsored carnivals, picnics, singing societies, and even Sunday schools. Under pressure from city officials, the local railway and electricity companies—which operated with municipal licenses—reduced their rates.

In office, Milwaukee’s Socialists expanded the city’s parks and library system and improved the public schools. They paid city employees union-level wages and granted municipal employees an eight-hour day. They adopted tough factory and building regulations. They reined in police brutality against striking workers and improved working conditions for rank-and-file cops. They improved the harbor, built municipal housing, and sponsored public markets. The Socialists had their own newspaper and sponsored carnivals, picnics, singing societies, and even Sunday schools. Under pressure from city officials, the local railway and electricity companies—which operated with municipal licenses—reduced their rates.

Grateful for these policies and programs, Milwaukee voters kept Socialists in office. They elected Daniel Hoan as mayor from 1916 to 1940, under whom Milwaukee was frequently cited for its clean, efficient management practices. In his 1999 book, The American Mayor, Melvin Holli reported that a survey of urban government experts voted Hoan as the eighth best mayor in U.S. history. Remarkably, Milwaukee voters elected another Socialist, Frank Zeidler, as their mayor in 1948, and he remained in office for twelve years at the height of the Cold War.

Without giving the progressives and the socialists the credit they deserved, many other cities eventually emulated these urban reforms. By the 1920s most major cities and some states had implemented reforms such as building codes, child labor laws, and the creation of public health departments. These urban reformers and radicals laid the foundation for the New Deal, which expanded urban progressivism by providing federal funds to improve conditions in cities, regulated banks and other big corporations, created government-subsidized housing for the working class, and established Social Security, the minimum wage, and unemployment insurance. Since the 1930s, progressive mayors—from New York’s Fiorello LaGuardia (1934-45) and Bridgeport’s Jasper McLevy (1933-57) to Chicago’s Harold Washington (1983-87) and Boston’s Ray Flynn (1984-93)—have challenged corporate prerogatives and adopted measures to make cities more livable and humane.

* * *

As more and more Americans associate capitalism with inequality, poverty, and corporate control, its alternative is starting to seem less foreign and outrageous.

Public opinion alone doesn’t translate into political change. But an upsurge of activism for social and economic justice might just. This year has seen a wave of unprecedented strikes at Walmart and in the fast food industry, with employee protests backed by a broad coalition of consumers, community groups, and unions calling for a $15 minimum wage (or, in the case of Walmart workers, a full-time salary of $25,000). Across the country, homeowners facing foreclosure due to reckless predatory loans have linked arms and resisted eviction, while community groups and unions push elected officials to hold major lenders accountable with fines, settlement agreements, and jail time for top executives.

These campaigns, alongside grassroots struggles for comprehensive immigration reform; multi-pronged protests by environmentalists aiming to stop the Keystone pipeline and push universities to divest from major energy corporations; prayer vigils, rallies, and civil disobedience in response to gun violence, restrictions on voting and reproductive rights, and overseas sweatshops; and a fierce campaign for gay and lesbian rights have emboldened a new wave of progressive urbanism.

This wave has yet to translate into policy in most cities, leaving urban communities on the defensive against a model of economic growth dictated by private investors and real estate developers. Even city officials sympathetic to social justice have worried that efforts to raise wages or regulate business practices would only scare away private capital, increase unemployment, and undermine a city’s tax base. Developers have relentlessly exploited those fears—which turn out to be misplaced.

Even in a global economy, local governments have considerable leverage over business practices, job creation, and workplace quality. Most jobs and industries are relatively immobile. Private hospitals, universities, hotels, utilities, and other “sticky” industries—as well as public enterprises such as airports, ports, transit systems, and government-run utilities—aren’t about to flee to Mexico or China if they have to raise wages or pay higher taxes. This makes threats to pull up stakes less compelling and gives the city (and progressives) more negotiating power.

* * *

Other cities have enacted “linked deposit” laws, and issued annual “report cards” on their lending activities, to push banks to invest in underserved areas as a condition of receiving municipal business. More than 150 localities have adopted “living wage” laws, and none have experienced the negative consequences that local business groups warned about. Building on the living wage model, progressive local officials understand that cities can focus municipal subsidies on industries and firms that provide decent pay, benefits, and upward mobility. Some cities have recently joined the movement to divest their pension funds from fossil fuel companies and gun manufacturers.

The Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE)—a coalition of labor, community, and faith-based groups founded in 1993—has been a pioneer in waging successful campaigns to give working class residents a stronger voice in local and regional government. LAANE pushed L.A. not only to adopt a strong living-wage law and the nation’s first community-benefit agreements, but also to improve working and environmental conditions at the city’s port and in its sanitation and recycling industry, thwart the invasion of low-wage big-box stores, and train inner-city residents for well-paying union jobs on government infrastructure projects.

Now, dozens of cities have adopted community-benefit agreements and inclusionary zoning laws to require developers to create good jobs and affordable housing, or to hire local residents on construction projects or as regular employees, without experiencing a flight of private investment. And in a growing number of metropolitan areas, cities and suburbs have forged peace agreements, such as regional tax-base sharing, to end the mindless competition that pits local jurisdictions against each other for private investment. In Cleveland and elsewhere, local governments have partnered with universities, hospitals, and community groups to promote community-owned or worker-owned cooperative businesses, as Gar Alperovitz documents in his fascinating book, What Then Must We Do?

Building on the legacies of organizations such as the Conference on State and Local Alternative Policy and Planners Network (started in the 1970s), new networks like Local Progress and the Partnership for Working Families are forging coalitions to connect labor, community, and faith-based groups across cities. Recognizing that cities still need a partner in the federal government, a growing number of mayors and local officials are also pushing to expand federal housing and infrastructure programs and to slash military spending and reinvest those tax dollars in urban areas, supported by groups such as the U.S. Conference of Mayors and Cities for Peace.

The time appears to be ripe for a new wave of urban reform. Both socialists like Seattle’s Sawant and progressives like New York’s de Blasio have a chance to popularize “left wing of the possible” ideas that seem bold but not preposterous. But as their socialist and progressive counterparts over the past century recognized, good ideas don’t become policy without social movements behind them.

Peter Dreier is professor of politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His most recent book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books, 2012). With John Mollenkopf and Todd Swanstrom, he is also coauthor of Place Matters: Metropolitics for the 21st Century, a third edition of which will be published in 2014 by University Press of Kansas.

Images:

1. “Bandit’s Roost” (Mulberry Street, New York City) by Jacob Riis (Wikimedia Commons)

2. Literary Digest, International News, 1920 (Wikimedia Commons)

Spread the word