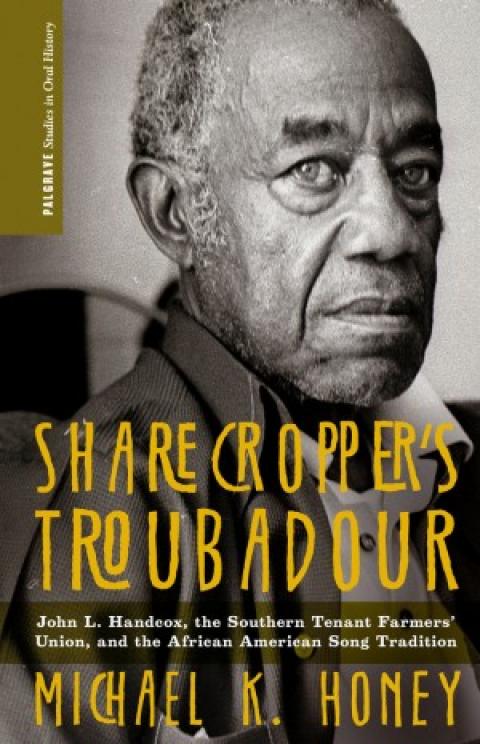

His new book, "Sharecropper's Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union and the African American Song Tradition" was published in November by Palgrave Macmillan. He answered a few questions about the book for UW Today.

Q: What's the concept behind this book?

A: The book is about the power of song and the human spirit. John Handcox, born in eastern Arkansas in 1904, grew up at one of the worst times and in one of the worst places to be black in America. He used his African-American song traditions to help desperately poor white and black agricultural workers organize together in Ku Klux Klan country during the Great Depression. They created one of the most remarkable social movements in American history. John showed that music is a powerful force to unite people for change.

Q: How did you come to write about John Handcox?

A: Folklorist and musician Pete Seeger introduced me to John in 1985 at a labor arts forum held outside of Washington, D.C. Ralph Rinzler, the director of the folklife program at the Smithsonian Institution, asked me to interview John about his life and music. The rest, as they say, is history.

Q: You write, "Much as rap artists did in later years, John weaponized the spoken word." It's a powerful phrase - would you expand on your meaning?

A. John painted word pictures to help people to see their plight and do something about it. He wrote:

How the sharecropper lives, the planter cares not how.

The Sharecropper works and he toils and sweats,

The planter brings him out in debt.

Planter what the heaven is the matter with you?

What has your labor ever done to you?

Upon his back you just sit and ride.

don't you think your labor gonna ever get tired?"

Q: Handcox disappeared from public life for decades. What were the circumstances of his departure and his return?

A: Plantation holders and their henchmen gathered a lynch mob to get him and John wanted to shoot it out, but his mother convinced him that the whole family would be killed if he did. John fled Arkansas for Memphis in 1937 and began writing songs.

He became a traveling organizer, poet, singer and songwriter for the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union. Jail, arrests, beatings and murder destroyed the union. John and his family went west to San Diego, and people in the union movement thought he had died. He worked as a carpenter and selling produce from his backyard until folklorists rediscovered him nearly 50 years later.

Q: You quote Handcox late in life saying, "What workers need today is more unity and less union." What caused this comment from him, and what is its meaning? Did it signal a change in his overall attitude toward unions?

A: To maintain the privileges of white workers, the carpenters union in San Diego first excluded him from work and then made him work at lower pay, until he broke down their barriers of racial discrimination. "More unity and less union" is what he demanded.

The existence of racial discrimination in the work world did not dim John's support for unions - quite the contrary - and he continued to sing "Solidarity Forever" as well as his composition, "Roll the Union On."

Q: Finally, what do you hope will be the legacy of John Handcox, assisted by this book?

A: John Handcox wanted us to remember and celebrate the fact that people can unite even under the worst of conditions and that song can help them to do it. His life and his songs and poems stand as a testament to this fact. Even as multinational corporations make inordinate profits by driving down the wages and living standards of workers today, it is always possible, John believed, "to make this a better world."

Hear John L. Handcox

Listen to the songs of John Handcox and Michael Honey describing the book at Honey's website.

Watch a video of John Handcox talking and singing "I Live On."

Spread the word