I met Ralph Fasanella in June 1988 at New York’s Roseland Ballroom during a tribute to Michael Harrington, the founder and co-chair of Democratic Socialists of America. Harrington was suffering from a cancer that would claim his life a year later. But in the summer of 1988 he was attempting to fight the disease, and was still actively working to build DSA and the American left – possibly working harder than ever, knowing how little time he had left. Harrington’s appreciative friends and supporters organized this tribute while Harrington was still with them, and hundreds of people turned out to hear a galaxy of stars of the left – including Barbara Ehrenreich, William Winpisinger, Edward Asner, Eleanor Holmes Norton – and others speak of what Harrington life and work meant to them and to politics in the United States.

Fasanella was there as well, not as a speaker but at a table selling print versions of his paintings. I had admired Fasanella’s work and went over to chat with him. About a minute into our conversation Fasanella, no doubt identifying me as someone with more free time than cash, said he had to step out for a few minutes, and would I watch his table for him? I readily agreed, and over the 15 minutes or so he was away I sold a couple of his prints. When he returned, he signed three prints and gave them to me as thank-you gifts. They now hang in my house as some of my most treasured possessions.

By then Fasanella had been “discovered;” a 1972 cover story in New York Magazine came after three decades of churning out his large, detail-packed canvases of the joy and pain of American working-class life – especially through the lens of early 20th-century New York. His paintings were already known and appreciated in union halls and to connoisseurs of “naïve” art (a label Fasanella hated), but after the story and a full-scale one-man show he became something of a celebrity in the art world.

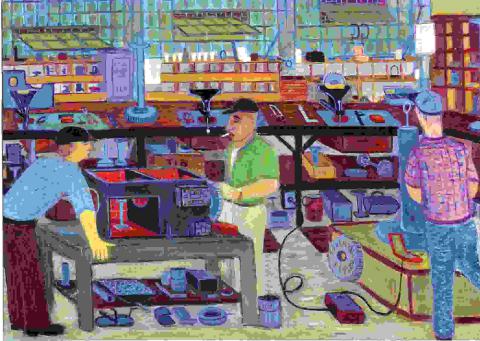

“Celebrity” was a label the blunt, plain-spoken Fasanella would wear uneasily, for his painting was always rooted in the everyday life of the American worker, the men and women who toiled long hours in the factory, struggled to provide for their families, and – a critical part of his narrative – fought for their rights by organizing unions and taking to the streets. But I think Fasanella, who died in 1997, would be pleased at the exhibit of 27 of his works currently on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Ralph Fasanella: Lest We Forget” arrives on the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth and covers works from 1947, near the beginning of his artistic career, to the end of his life. The exhibit is only a slice of Fasanella’s extensive body of work, but includes some of his best and most representative paintings.

Accompanying the May 2 opening of the exhibit was a showing of the early 1990s documentary “Fasanella” at AFL-CIO headquarters, part of DC LaborFest. Appearing at the showing were Fasanella’s son Marc and two grandchildren, as well as Glen Pearcy, the film’s producer. A short clip from the film runs at the Smithsonian exhibit.

Fasanella never took an art lesson, and his paintings were dismissed by some critics for their lack of polish and their almost-but-not-quite realism. Perhaps most of all, Fasanella fell outside the conventions of late 20th-century art because his paintings were about something; they had a point of view and lacked the fashionable detachment of the high-art circles. Fasanella worked for years as a union organizer before taking up painting, and labor struggles and the effort to organize unions are the subjects of many of his paintings. The 1912 Lawrence, Mass. “Bread and Roses” textile workers’ strike is featured in several of his paintings, including his monumental 1977 work “Meeting at the Commons: Lawrence 1912” with its dramatic scenario of a huge workers’ demonstration under empty factory windows and troops marching to suppressing the uprising. A more somber work is “Mill Worker: Night Shift” with women visible in the factory windows, Hopperesque in their lone liness and isolation.

Fasanella drew from his own family life in his paintings, especially from his childhood in which his Italian immigrant parents struggled to support a growing family. His father Joe, an iceman, consumed by anger and bitterness over hard work that failed to lift him and his family out of poverty, abandoned the family when Ralph was a child. A series of surreal paintings from the 1950s depict Joe as a crucified Christ figure, with ice tongs serving as a crown of thorns. Fasanella’s depictions of his family culminate in his 1972 “Family Supper.” An image of Fasanella’s mother Ginevre dominates a scene reminiscent of Da Vinci’s “Last Supper,” and the missing Joe is visible in his familiar crucifixion pose on a wall calendar. The motto “Lest We Forget” in inscribed in brickwork above the scene.

From early in his development in his painter, many of Fasanella’s works had an explicitly political edge. One of his earliest paintings, 1947’s “Pie in the Sky” – the title drawn from the chorus of the old Joe Hill song “The Preacher and the Slave” – contrasts scenes of poverty and hardship with a gleaming stained-glass church that seeks to distract the masses with promises of heavenly riches. His political vision sharpened in the 1950s with complex, multilayered canvasses attacking McCarthyism and depicting Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, executed for alleged spying, as sacrifices to the era’s hysteria. “McCarthy Press” centers around a pyramid of news headlines – not only political news but also sports and Hollywood gossip – as a crane lowers the Rosenbergs’ coffin into the ground. “The Rosenberg’s Grey Day” shows the couple stoically awaiting their fate, their children playing at their sides, while all around are images of incarcerated prisoners, a “Save the Rosenbergs” demonstration, a garden party, laborers hard at work in a factory. Even in the face of momentous events, life goes on, Fasanella tells us.

Perhaps the most disturbing canvas in the exhibit is “An American Tragedy,” which tells numerous stories within its 40x90 inches. The central theme is the assassination of President Kennedy, who is depicted as yet another sacrifice to the greed and reactionary politics of the time. One has to look hard to spot Oswald and his rifle, for in Fasanella’s telling the assassin was only a tool of larger forces. The picture includes klansmen in full regalia, civil rights workers attacked by police, Martin Luther King Jr. leading a peaceful demonstration, Barry Goldwater heading a triumphal motorcade, and most prominently a man dressed in a mix of business and KKK attire, riding a black horse that tramples Kennedy’s grave.

Fasanella’s final painting, “Farewell Comrade/End of the Cold War,” was perhaps his most political statement, and the one in which he most clearly aired his socialist ideals. Here Lenin is being laid to rest in a crowded stadium, surrounded by the names of prominent American leftists and socialists (John Reed, Jack London), and news headlines such as “Reagan Triples Deficit with Military.” The message is clear: Communism’s death took with it a share of the socialist ideals that it tried to embody, however imperfectly.

Yet Fasanella’s paintings are not all workers’ struggles and political anguish. Many of his works also depict the joy of community, of neighborhood, or workingmen and their families enjoying a respite from difficult lives. In particular, images of baseball run through his works, both organized games – as in “Night Game: Practice Time” -- and the impromptu street games of children. But the sport can take on a darker cast, as mere games in the face of tragedy – as in 1979’s “Watergate,” as a baseball game continues in the midst of images of American corruption and greed.

In the documentary, a student asks Fasanella which famous artist most inspired him. He cites Van Gogh, and his layering of paints and color patterns do bring do bring that painter to mind. But perhaps the “fine” artist Fasanella more closely channeled was Marc Chagall, with whom he shared the allegorical themes, vivid colors and his deliberate use of figures that were out of scale to each other.

But in the end, Fasanella copied no one: not Van Gogh, nor Grandma Moses or Edward Hicks to whom he was often compared. He was sui generis, and when his paintings finally came to be appreciated, it was for their uniqueness, not their adherence to any school or formal style. Most of all, they are celebrated for forcefully conveying the ideals he lived and worked by, as summarized in his motto: “Remember who you are. Remember where you came from. Don’t forget the past. Change the world.”

The Smithsonian exhibit runs through August 3. In addition to the exhibit, a good source on Fasanella’s life and work is Patrick Wilson’s 1973 book Fasanella’s City: The paintings of Ralph Fasanella with the story of his life and art (Ballantine Books).

[Many thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.]

Spread the word