In late February, Senator Kay Hagan of North Carolina formally announced her reelection bid. The moderate Democrat, a former bank executive who rode President Obama’s coattails to a narrow upset victory over Republican incumbent Elizabeth Dole in 2008, was heading into a tough campaign against Thom Tillis, the speaker of the state House of Representatives. Americans for Prosperity, the Tea Party group funded by the billionaire Koch brothers, had already dished out more than $3 million for ads attacking Hagan — a mere precursor of an ugly eight months to come. But on this day, at least, the senator figured to have the news cycle all to herself, with Tar Heel TV stations broadcasting the usual announcement fanfare of broad smiles and soundbite-worthy platitudes.

All went according to plan until pesky reporters started asking Hagan about her vote for the Affordable Care Act, and about her past echoing of Obama’s claim that “if you like your insurance plan, you can keep it.” She’d been asked such questions dozens of times, no doubt, but the senator still had no answer. As campaign staffers anxiously whisked her away from the podium and outside to her waiting car, reporters chased Hagan, repeating the Obamacare questions. Finally, she responded, somewhat mysteriously, “It wasn’t clear that insurance companies were selling substandard policies.” Cue the evening sound bite: the backside of Senator Hagan fleeing from journalists in her bright pink announcement-day dress, dodging questions about a seminal controversy. “Dodging,” along with its synonym “ducking,” would soon become the verb of choice for headlines about the Hagan campaign.

It was not, to say the least, what the senator’s strategists had in mind. But Hagan’s tentative attitude has become a common theme across the South this year. As the region has become the Republican Party’s national fortress, Southern Democrats have won Senate seats by playing down their ties to their party.This year, six Democrats — three incumbents and three challengers — are waging competitive campaigns. The results in North Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi could determine whether Obama faces a hostile Senate for his last two years in the White House. (Republicans need to pick up six seats to gain control, and only about 15 are competitive nationally.)

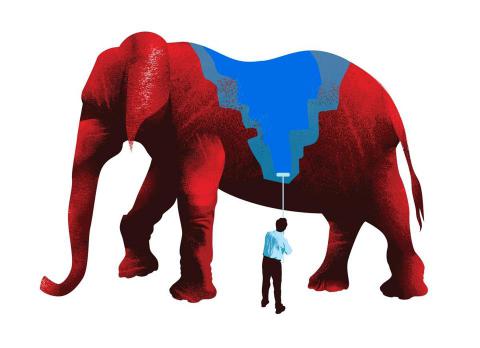

The question is whether Democrats in these states are better served by following the region’s five-decade-long drift toward the GOP — or by betting that the climate is finally changing in their favor.

It’s a sign of things to come in states like North Carolina, where large influxes of Latino immigrants and “relocated Yankees,” both black and white, are tilting the demographic balance toward the Democrats and inspiring a new progressive movement. But despite Obama’s own surprising Southern breakthroughs — after Al Gore and John Kerry lost the entire region, he won three large Southern states in 2008 and two in 2012, falling just short in North Carolina — the region’s blue future is still a long-term proposition. Candidates like Hagan are stuck between the past, when Southern Democrats’ recipe for victory involved courting white moderates and conservatives, and a future in which they’ll be able to successfully campaign as full-throated, national-style Democrats. To win, Hagan and her compatriots must simultaneously woo independent-minded whites while persuading massive numbers of young voters and nonwhites, who lean left on both economic and social issues, to join them.

It’s an awkward proposition, to be sure. But the Democratic contenders have appeared hell-bent on making it look downright impossible.

A few months after Hagan fumbled her big day, Georgia Democrat Michelle Nunn — a lavishly funded first-time candidate who is the daughter of much-loved former Senator Sam Nunn — had her moment in the national spotlight, courtesy of MSNBC. But when Nunn, whom The Guardian newspaper has described as exerting “robot-like control” over her carefully scripted campaign, was asked by the friendly reporter about her stance on Obamacare, the script turned to mush. Pressed on whether she’d have voted for the Affordable Care Act, Nunn prevaricated, kvetched, and weaved, before finally offering that “it’s impossible to look back retrospectively.” In a subsequent interview with Politico, Nunn — who’s running in a state that is now more than 40 percent nonwhite and headed toward being “majority-minority” — even declined to say whether she’d support Harry Reid as Senate majority leader or whether Obama is doing a good job.

Nunn, like Hagan, is running a classic Southern Democratic campaign, in which the great goal is to come across as a milder version of a Republican. The same is true for incumbent senators Mark Pryor of Arkansas and Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, and for Democratic challengers Travis Childers in Mississippi and Alison Lundergan Grimes, the young Kentucky secretary of state who’s waging a fierce battle to unseat Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. The demographics in those four states aren’t trending Democratic the way North Carolina or Georgia are, but the candidates face the same dilemma: How do you sound like the future while running a campaign that’s rooted in the past?

Only Landrieu, who’s running a tight race for a fourth term in a state that is one-third African-American, has found an issue to run on — as opposed to spending all her time running away from sticky issues like Obamacare, which she has (mostly) defended without reservation. But Landrieu’s big selling point is hardly a traditional Democratic one. As the newly minted chair of the Senate Energy Committee, she’s cast herself as an ardent booster of the state’s oil and gas industries, championing the Keystone pipeline and distancing herself from Obama by loudly and frequently decrying the Obama EPA’s new greenhouse-gas regulations. “I’ve been in Washington a long time — some say too long, but I hope not,” Landrieu recently told the Louisiana Farm Bureau Federation Convention. “My seniority is your clout.” An April TV spot narrated by the wonderfully named Louisiana shipbuilder Boysie Bollinger — a prominent Republican donor, no less — put a slightly different spin on the same theme: “Louisiana can’t afford to lose Mary Landrieu.”

Elsewhere in the South, the Democrats’ messages are comically muddled. Their races are competitive mostly because of the deep flaws in their Republican opponents. In Kentucky, Grimes has a shot because McConnell, a leader in the seismically unpopular Congress, has approval ratings that are as bad as Obama’s. The Republican seeking to unseat Hagan in North Carolina, Thom Tillis, has a similar problem: He’s the most prominent leader of a legislature whose right-wing policy making has made it more radioactive than Obama. Mississippi’s longtime Republican senator, Thad Cochran, narrowly survived a runoff in late June with Tea Party challenger Chris McDaniel, and at 76, he’s shown his age on the campaign trail; asked at one point what he’d do after the election, Cochran replied, all too honestly, that he’d “take a nap.” Now the senator is fending off legal challenges as McDaniel and the Tea Party furiously claim voter fraud in the runoff. In Arkansas, pundits considered Democratic Senator Mark Pryor a likely loser against Representative Tom Cotton, a young war veteran and rising Tea Party star — until Cotton revealed himself to be an unwavering right-wing ideologue and a cold fish on the campaign trail. “I’m warm, dammit,” he insisted to a visiting national reporter in June.

But for Democrats, “I’m not that other guy you can’t stand” is hardly a campaign message that will motivate the base. That’s especially true in a midterm year, when it’s the most reliably Democratic voters — young people and minorities — who are likeliest to sit out election day. “They’re going to stay home again unless we make sure they understand why there’s something big at stake in 2014,” says Page Gleason, who runs the state’s new progressive voter-mobilization group, Pro-Georgia. Nunn, whose campaign ads don’t identify her as a Democrat, is doing them no favors.

If Democratic-leaning voters in Georgia voted in similar numbers to Republicans, the state would already be blue. But the Democrats’ old habit of running Republican Lite campaigns, while it’s given them a chance to win the occasional statewide election in a good year, has convinced much of what could be the base that there’s little reason to bother with voting. Statewide, more than 800,000 eligible nonwhites are nonvoters — much more than what it would have taken for Obama, who ran no campaign in the state, to carry Georgia in 2008.“The old blue-dog model doesn’t work anymore,” says Ed Kilgore, a Georgia native and Democratic strategist who helped craft that model during his years with the centrist Democratic Leadership Council. “The people you’re appealing to aren’t going to vote for any Democrat anymore. You just don’t go right on every conceivable issue.” But that is exactly what his old friend Nunn — aside from her progressive stances on abortion rights and gay marriage, which she doesn’t like to talk about — is doing. Her platform consists of reducing corporate tax rates, entitlement “reform” (read: cuts) and debt reduction, supporting the Keystone pipeline, and cheering for military strikes in Syria. It’s not exactly catnip for the state’s emerging majority.The surest way to fire up young people and minorities in Georgia — and North Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana — would be for the Democratic candidates to grit their teeth, take the plunge, and embrace Obama, even just a little. There’s a reason, after all, why turnout in most Southern states skyrocketed with the president topping the ticket. The voting rate in North Carolina went from 51 percent in 2000 to 66 percent in 2008; in Georgia and Mississippi, turnout was even lower in 2000 and 2004 than in North Carolina, but rose to more than 60 percent in the Obama years. While the president might not exactly be beloved in a state like Georgia, his approval ratings there are exactly the same as his national average: 42 percent.

Nunn is running neck and neck for an open seat against two potential Republican challengers. (The GOP primary is Tuesday.) Surely a big late-October rally in Atlanta, with Obama embracing Nunn on a stage packed with homegrown civil-rights legends like Andrew Young and Representative John Lewis, would be exactly what Nunn, would need to push her over the top — and, very likely, keep Democrats in control of the Senate. Obama’s presence could also fire up conservative whites, but that would make a marginal difference: It’s those very voters who tend to show up for mid-term elections, and they’re already itching to cast one last anti-Obama vote in 2014.

No matter. Southern Democrats like Nunn are about as likely to welcome Obama as they are to make a public announcement that they’ve converted to French socialism. Southern Democrats have turned Obama-avoidance into a virtual art form — even Hagan, who wouldn’t have a Senate seat without the success of the Obama machine in 2008. In January, when the president visited Raleigh to announce a $140 million manufacturing initiative in the state, Hagan said she was too busy in Washington to make the trip. Hagan’s snub turned into one more public-relations fiasco when Obama pointedly brought up her absence and cheekily gave her the kind of endorsement that gives her campaign staff nightmares: “Your senator, Kay Hagan, couldn’t be here,” he said, “but I wanted to thank her publicly for the great work she’s been doing.” Most of the next day’s headlines read a lot like the one in the New York Daily News: “Sen. Kay Hagan avoids Obama during his North Carolina visit.”

What might happen if Democrats in the fast-evolving 21st-century South ran as honest-to-goodness, true-blue Democrats? Because the old Republican Lite habit dies hard — and because politicians of all stripes are timid by nature — we won’t find out this year. But it won’t be long. Perhaps in 2016, maybe in 2020, the mold will be broken: A new-style Southern Democrat will run in a state like Georgia or North Carolina or Texas and win with a full-throated progressive message. The demographics make it inevitable. And the result ultimately will be a whole new national political order. No longer will it be Southerners in Congress who are the stubborn impediments to progressive reform, as they’ve been for 150 years. And no longer will Republicans have a stranglehold on the region in presidential elections. The five largest Southern states — Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina, Texas, and Florida — account for most of the region’s electoral votes. They’re also the states where conservative whites are losing their hegemony by the day. How will the GOP carry national elections without them?

By the next decade, if demographics are (and they usually are) destiny, it will be Southern Republicans who are dodging and ducking and triangulating, conjuring ways to hold on to their aging and shrinking white base while appropriating Democratic issues and rhetoric to woo the new progressive majority. If they need tactical advice, they can always hire Kay Hagan or Michelle Nunn as campaign consultants. Their species of Southern Democrat will be, by then, a fading relic of a strange, distant, and inexplicable past.

[Bob Moser, a senior editor at National Journal, is the author of “Blue Dixie.” ]

Spread the word