Child Migrants Have Been Coming to America Alone Since Ellis Island - And no, we didn't just send them packing

- Child Migrants Have Been Coming to America Alone Since Ellis Island - Tasneem Raja (Mother Jones)

- Support Child Immigrants - Share this Image - unitedwedream.org

- These Are the Places Central American Child Migrants Are Fleeing - By Ian Gordon (Mother Jones)

By Tasneem Raja

July 18, 2014

Mother Jones

An unaccompanied child migrant was the first person in line on opening day of the new immigration station at Ellis Island. Her name was Annie Moore, and that day, January 1, 1892, happened to be her 15th birthday. She had traveled with her two little brothers from Cork County, Ireland, and when they walked off the gangplank, she was awarded a certificate and a $10 gold coin for being the first to register. Today, a statue of Annie stands on the island, a testament to the courage of millions of children who passed through those same doors, often traveling without an older family member to help them along.

Of course, not everyone was lining up to give Annie and her fellow passengers a warm welcome. Alarmists painted immigrants-children included-as disease-ridden job stealers bent on destroying the American way of life. And they're still at it. On a CNN segment about the current crisis of child migrants from Central and South America, Michele Bachmann used the word "invaders" and warned of rape and other dangers posed to Americans by the influx. And last week, National Review scoffed at appeals to American ideals of compassion and charity, claiming Ellis Island officials had a strict send-'em-back policy when it came to children showing up alone.

That's not true, according to Barry Moreno, a librarian at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum and author of the book Children of Ellis Island. The Immigration Act of 1907 did indeed declare that unaccompanied children under 16 were not permitted to enter in the normal fashion. But it didn't send them packing, either. Instead, the act set up a system in which unaccompanied children-many of whom were orphans-were kept in detention awaiting a special inquiry with immigration inspectors to determine their fate. At these hearings, local missionaries, synagogues, immigrant aid societies, and private citizens would often step in and offer to take guardianship of the child, says Moreno.

In Annie's case, her parents were waiting to receive her; they'd taken the same journey to New York three years before, looking for work. But according to Moreno, thousands of unaccompanied children came over without friends or family on the other side of the crossing, many of them stowaways. Moreno doesn't know of an official count of how many children were naturalized this way, but he says it was fairly common. And he can point to at least one great success story, that of Henry Armetta, a 15-year-old stowaway from Palermo, Italy, who was sponsored by a local Italian man and went on to be an actor in films with Judy Garland and the Marx Brothers. "He's one of the best known of the Ellis Island stowaways," Moreno says.

Eight orphan children whose mothers were killed in a Russian pogrom. They were brought to Ellis Island in 1908.

Augustus Sherman/National Parks Service

Other children journeyed to Ellis Island alone because they had lost their parents, often to war or famine, and had been sponsored by immigrant aid societies and other charities in America. The picture above shows eight Jewish children whose mothers had been killed in a Russian pogrom in 1905. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society had obtained "bonds" to sponsor their immigration, and they arrived at Ellis Island in 1908. As Moreno notes in his book, thousands of orphans came over thanks to such bonds, and after landing, many would travel on "orphan trains" to farms and small towns where their patrons had arranged their stay.

A German refugee child and Superman devotee at the New York City Children's Colony, a school for refugee children run by Viennese immigrants

Marjory Collins/Library of Congress

Ellis Island officials made several efforts to care for children detained on the island-those with parents and those without-who could be there for weeks at a time. Around 1900 a playground was constructed there with a sandbox, swings, and slides. A group of about a dozen women known as "matrons" played games and sang songs with the children, many of whom they couldn't easily communicate with due to language barriers. Later, a school room was created for them, and the Red Cross supplied a radio for the children to listen to.

And of course, many of those kids grew up to work tough jobs, start new businesses and create new jobs, and pass significant amounts of wealth down to some of the very folks clamoring to "send 'em back" today.

Statue of Annie Moore and her brothers in Cobh, Ireland. There's another statue of Moore at Ellis Island.

jafsegal/Flickr // Mother Jones

[Tasneem Raja is Mother Jones' Interactive Editor. She specializes in web app production, interactive graphics, and user interface design. She can be reached on Twitter ]

Support Child Immigrants - Share this Image

caption - Stand With Refugee Children #TheyAreChildren

http://unitedwedream.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/refugee_children_fb…

These Are the Places Central American Child Migrants Are Fleeing

By Ian Gordon

June 27, 2014

Mother Jones

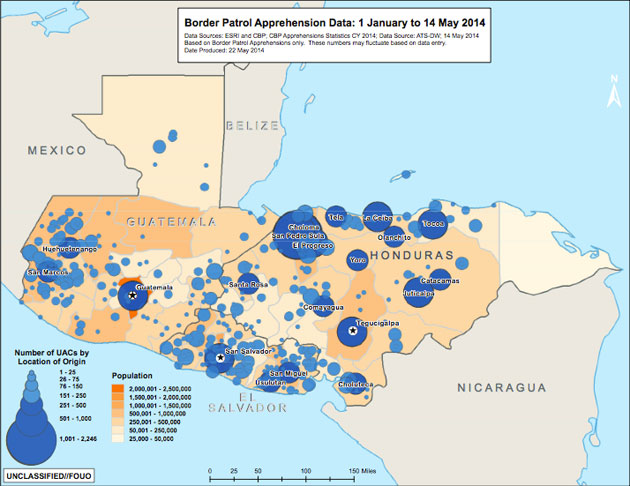

Department of Homeland Security // Washington Office on Latin America

A recently produced infographic from the Department of Homeland Security shows that the majority of unaccompanied children coming to the United States are from some of the most violent and impoverished parts of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

The map documents the origins of child migrants apprehended by the Border Patrol from January 1 to May 14. It was made public by Adam Isaacson of the Washington Office on Latin America, a human rights organization, and it includes the following analysis about the surge in child migrants:

Many Guatemalan children come from rural areas, indicating that they are probably seeking economic opportunities in the US. Salvadoran and Honduran children, on the other hand, come from extremely violent regions where they probably perceive the risk of traveling alone to the US preferable to remaining at home.

This echoes what I found in my yearlong investigation into the explosion of unaccompanied child migrants arriving to the United States. As I wrote in the July/August issue of Mother Jones:

Although some have traveled from as far away as Sri Lanka and Tanzania, the bulk are minors from Mexico and from Central America's so-called Northern Triangle-Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, which together account for 74 percent of the surge. Long plagued by instability and unrest, these countries have grown especially dangerous in recent years: Honduras imploded following a military coup in 2009 and now has the world's highest murder rate. El Salvador has the second-highest, despite the 2012 gang truce between Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18. Guatemala, new territory for the Zetas cartel, has the fifth-highest murder rate; meanwhile, the cost of tortillas has doubled as corn prices have skyrocketed due to increased American ethanol production (Guatemala imports half of its corn) and the conversion of farmland to sugarcane and oil palm for biofuel.

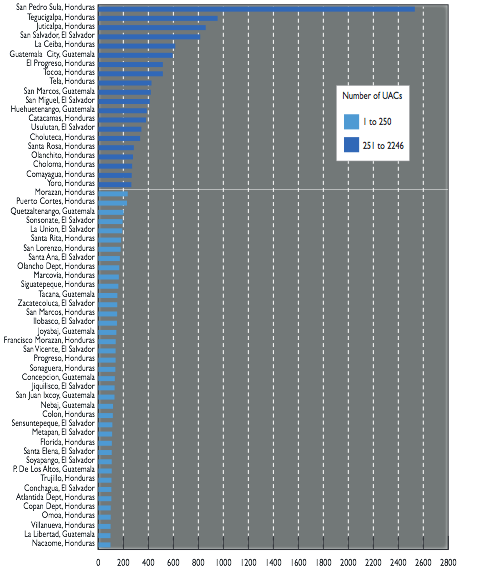

Below is a more granular look at where kids are coming from, also produced by DHS. San Pedro Sula, the world's most violent city, was home to the largest number of child migrants caught by the Border Patrol (more than 2,500). Honduras' capital, Tegucigalpa, sent the second-most kids, fewer than 1,000.

[Ian Gordon reports on immigration, sports, and Latin America for Mother Jones. Email him: igordon@motherjones.com. Twitter ]

http://twitter.com/id_gordon

Spread the word