There were leaflets, a manifesto, and this warning: “On campus after campus, we will chase you old goats out of power. Then, in the months and years that follow, we will begin the work of reprogramming the doomsday machine.”

On Friday, on the eve of the annual meeting of The American Economic Association in Boston, attended by many of the top economists in the United States, the agents of the heterodoxy had come to declare war on the profession. The small group threw their messages onto the side of the Sheraton Boston in glowing, six-foot tall letters: “BEFORE ECONOMICS CAN PROGRESS, IT MUST ABANDON ITS SUICIDAL FORMALISM.”

“The projection’s looking great,” said Keith Harrington, bearded, bespectacled, and bundled-up, as the sun set in the subzero weather.

“It’s a twelve-thousand lumen projector,” said Kyle Depew, who had schlepped the suitcase-sized thing from New York that day.

Harrington, a community organizer and videographer, once worked as a climate change activist. But after a few years he came to see that the real fight was elsewhere. “The type of activism we were doing around climate was running into systemic challenges,” he said. “We couldn’t get the types of climate change policies we need without system change, without addressing questions in economics like growth and limits to growth.”

Harrington now runs a campaign called Kick it Over, which aims to combat what it describes as “the fantasy world of neoclassical economics — a faith-based religion of perfect markets, enlightened consumers and infinite growth that shapes the fates of billions.” The project is connected with the anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters, which had gestated the original idea behind the Occupy Wall Street movement. Harrington, who studied alternative economics at The New School, hopes to reform the profession from the inside, starting with the way it’s taught.

“When I was in school, I started realizing how limited was the range of economic ideas that students were exposed to in the classroom,” he said. “Neoclassicism is essentially the standard for 95 percent of the graduate departments in the country.”

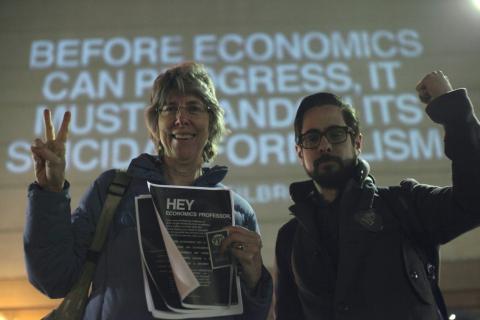

Through mailing lists and word of mouth, Harrington recruited economics students from around the country to hold the campaign’s first official demonstration here, at this tweedy conference of academics. About nine students showed up at the Sheraton on Friday night to hand out fliers and smash the orthodoxy.

“We were just very disillusioned students for the first couple of years that we were taking econ,” said Jess Fuller, a senior at the University of Vermont majoring in economics and history. “We just felt it was very out of touch with reality, and there were some questions that never seemed to be answered or even asked in the first place.”

Fuller, who also works with a feminist group on her campus, says that mainstream economics doesn’t do a good enough job incorporating perspectives on gender and class.

“There is a sort of value judgment to the way economics is taught,” added Aparna Gopalan, a sophomore at Connecticut College. She recommended a book on Buddhist economics. “From that point of view, the GDP is so funny,” she said. “It makes no sense! It’s like, they’re measuring how many commodities are bought and sold in a year, but the point isn’t the commodities, you know? It’s the hours of labor.”

On Friday night after the demonstration, undergraduates Jess Fuller, Aparna Gopalan, and Kevin Santamaria talked with Stephanie Seguino (left), a professor of economics at the University of Vermont, and a member of the Union for Radical Political Economics. (Jeff Guo / The Washington Post)

On Friday night, students were joined by allies like Julie Matthaei, an economics professor at Wellesley who studies Marxist-feminist economic theory.

“The concepts are very different,” she said. “For example, in mainstream economics there aren’t any classes. Everyone’s just an individual, they own factors, and they own means of production, and they get paid for them. Whereas for Marx, and for radicals, it’s different if you work vs. if you own.”

Matthaei is a member of the Union for Radical Political Economics. The coordinator of that group, Frances Boyes, was also nearby. She had passed out about 40 fliers, but there was one stack that needed to be amended. “HEY MR. ECONOMICS PROFESSOR,” they said, before launching into a critique of the profession.

“There are lady economists, too,” Boyes explained.

After about 30 minutes, Harrington called everyone together to debrief, and to prepare for the days ahead. During the conference over the weekend, the students would attend various panels to demonstrate, and to ask pointed questions. On Saturday, they crashed the debate between economists Thomas Piketty and Gregory Mankiw with a projection criticizing Mankiw.

Activist Keith Harrington used a pocket projector to put quotes on the walls inside panel discussions during the American Economic Association conference on Saturday and Sunday. (Image courtesy of Keith Harrington)

On Sunday, they hectored Carmen Reinhart, an economist at Harvard who studies financial crises. A few years ago, Reinhart and her colleague Kenneth Rogoff had become famous for observing a connection between high debt in a country and low GDP growth. Their paper was then the center of a controversy in 2013 when economists at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst pointed out an error in an Excel spreadsheet.

Reinhart, on Sunday, was presenting a paper on the statistics when countries were unable to pay back their debts in full.

Harrington said: “She’s continuing on her focus, which is essentially public debt, and we went in there, and we said: ‘You’re now going to be releasing a new study that’s even more massive and potentially more consequential than the last one. Have you had a graduate student go through and check your data for errors?’”

“She was just livid,” Harrington said. Using a pocket projector, he projected a slide quoting Paul Krugman on to the wall, which declared that Reinhart and Rogoff have “done a great deal of harm.”

Activist Keith Harrington used a pocket projector to put quotes on the walls inside panel discussions during the American Economic Association conference on Saturday and Sunday. (Image courtesy of Keith Harrington)

Reinhart said that the episode seemed like a personal attack rather than an argument for other perspectives in economics. The irony of the matter, she noted, was that her talk that day concerned a non-mainstream corner of macroeconomics.

“If they understand — if they understand, which is a big if — what heterodox means, this was actually a session precisely on the alternative approaches to debt reduction, the debt relief associated with haircuts,” she said.

“If they want to say ‘we don’t like you, and we want to make it personal,’ this is not the venue for that.”

Jeff Guo is a staff writer for Storyline. He's from Maryland (but outside the Beltway). Follow him on Twitter: @_jeffguo.

Spread the word