ATTICA, N.Y. — On the evening of Aug. 9, 2011, one month before the 40th anniversary of the bloody Attica prison riot, a guard in that remote facility in western New York was distributing mail to inmates in C Block, one of the vast tiers of cells nestled behind its towering 30-foot walls.

The prisoners were rowdy that night, talking loudly as they mingled on the gallery outside their cells, a State Police inquiry found. Frustrated, an officer shouted into the din: “Shut the (expletive) up.”

Normally, that would be enough to bring quiet to C Block, where guards who work the 3 to 11 p.m. shift are known for strict, sometimes violent, enforcement of the rules. This night, somewhere on the gallery, a prisoner shouted back, bellowing “You shut the (expletive) up.” Emboldened, the shouter taunted the officer with an obscene suggestion.

Inmates were immediately ordered to retreat to their cells and “lock in.” Thirty minutes later, three officers, led by a sergeant, marched down the corridor. They stopped at the cell of George Williams, a 29-year-old African-American from New Jersey who was serving a sentence of two to four years for robbing two jewelry stores in Manhattan.

Mr. Williams had been transferred to Attica that January following an altercation with other inmates at a different facility. He had just four months to serve before he was to be released. He was doing his best to stay out of trouble. His plan was to go home to New Brunswick and try to find work as a barber. That evening, Mr. Williams remembers, he had been in his cell watching the rap stars Lil Wayne and Young Jeezy on television, and missed the shouting on the cellblock. The guards ordered him to strip for a search and then marched him down the hall to a darkened dayroom used for meetings and classes for what they told him would be a urine test.

Mr. Williams is 5-foot-8, and a solid 170 pounds. But corrections officers tend toward linebacker size, and the three officers towered over him. The smallest was Sgt. Sean Warner, 37, at 5-foot-11, 240 pounds. Beside him was Officer Keith Swack, 37, a burly 6-foot-3 and some 300 pounds. A third officer was standing behind the cell door. Mr. Williams thought it was Officer Matthew Rademacher, 29, who had followed his father into the job six years earlier. Officer Rademacher was six feet tall and weighed 260 pounds. All three men are white and had goatees at the time.

George Williams was beaten while he was an inmate at Attica prison in western New York. Among his injuries were broken legs, a broken shoulder and eye socket and cracked ribs. Credit Damon Winter/The New York Times

Mr. Williams was wondering why a sergeant would be doing the grunt work of conducting an impromptu drug test when, he said, a fist hammered him hard on the right side of his rib cage. He doubled up, collapsing to the floor. More blows rained down. Mr. Williams tried to curl up to protect himself from the pummeling of batons, fists and kicks. Someone jumped on his ankle. He screamed in pain. He opened his eyes to see a guard aiming a kick at his head, as though punting a football. I’m going to die here, he thought.

Inmates in cells across from the dayroom watched the attack, among them a convict named Charles Bisesi, 67, who saw Mr. Williams pitched face-first onto the floor. He saw guards kick Mr. Williams in the head and face, and strike him with their heavy wooden batons. Mr. Bisesi estimated that Mr. Williams had been kicked up to 50 times, and struck with a dozen more blows from nightsticks, thwacks delivered with such force that Mr. Bisesi could hear the thud as wood hit flesh. He also heard Mr. Williams begging for his life, cries loud enough that prisoners two floors below heard them as well.

A couple of minutes after the beating began, one of the guards loudly rapped his baton on the floor. At the signal, more guards rushed upstairs and into the dayroom. Witnesses differed on the number. Some said that as many as 12 officers had plunged into the scrum. Others recalled seeing two or three. All agreed that when they were finished, Mr. Williams could not walk.

His ordeal is the subject of an unprecedented trial scheduled to open on Monday in western New York. Three guards — Sergeant Warner and Officers Rademacher and Swack — face charges stemming from the beating that night. All three have pleaded not guilty. An examination of this case and dozens of others offers a vivid lesson in the intractable culture of prison brutality, especially given the notoriety of Attica, which entered the cultural lexicon as a synonym for prison havoc after 43 men died there in 1971 as the state suppressed an uprising by inmates. This account is based on investigative reports and court filings, as well as interviews with people on both sides of the bars at Attica, state officials and prison reform advocates.

From left, Sgt. Sean Warner, Officer Keith Swack and Officer Matthew Rademacher. Credit New York State Police

After the beating ended, an inmate who was across from the dayroom, Maurice Mayfield, watched as an officer stepped on a plastic safety razor and pried out the blade. “We got the weapon,” Mr. Mayfield heard the guard yell.

Mr. Williams was handcuffed and pulled to the top of a staircase. “Walk down or we’ll push you down,” he heard someone say. He could not walk, he answered. His ankle was broken. As he spoke, he was shoved from behind. He plunged down the stairs, crashing onto his shoulder at the bottom. When guards picked him up again, he said, one of them grabbed his head and smashed his face into the wall. He was left there, staring at the splatter of his own blood on the wall in front of him.

When an inmate is accused of serious violations in one of New York State’s maximum security prisons, standard procedure calls for him to be placed in solitary confinement in the Special Housing Unit. Stays in “the Box,” as the unit is called, can last weeks, months, even years. But when the detail arrived at the Box with Mr. Williams that night, the officer in charge refused to accept him, telling the officers to take him to the prison infirmary. “We can’t take him in here looking like that,” Mr. Williams heard the officer say.

Extensive Injuries

At the infirmary, Katherine Tara, a nurse who had been working at Attica for just 10 months, saw cuts over Mr. Williams’s eyes and blood on his mouth and clothing. He told her his vision was blurry and that he thought his ribs were broken. With officers nearby, he said nothing about how he had been hurt. Ms. Tara later told investigators that she had treated other inmates in what are called “use of force” cases. This one was excessive, she said. She called the prison’s medical doctor, who agreed with her: Mr. Williams needed to go to an outside hospital.

As Mr. Williams waited in the infirmary, several guards involved in the episode arrived, including Officers Rademacher and Swack. Mr. Williams heard someone boast that there would be no consequences for the beating: “The (expletive) that happened upstairs isn’t going to be nothing.”

Mr. Williams was taken first to a hospital in Warsaw, the county seat of Wyoming County, where Attica is. But the injuries were too severe for the doctors there to treat. Packed up again, he was driven to Erie County Medical Center in Buffalo, 50 miles away.

As he rode the highways of western New York that sweltering night, Mr. Williams worried that if he were to return to Attica, he would be killed. He asked a medical attendant to lend him his cellphone so he could call his family. The attendant refused.

In Buffalo, his injuries were tallied: a broken shoulder, several cracked ribs and two broken legs, one of which required surgery. Doctors realigned it, using a plate and six screws. Mr. Williams also had a severe fracture of the orbit surrounding his left eye, a large amount of blood lodged in his left maxillary sinus, and multiple cuts and bruises.

One doctor who treated Mr. Williams asked a guard what had happened. He should not have had the weapon, the guard replied.

Back at Attica, the same explanation was entered on official reports. In what is known as an unusual incident memo, guards detailed Mr. Williams’s alleged infractions, including the razor blade and ice pick-like shaft they said they found on him. On C Block, an inmate named Raymond Sanabria, who worked as a porter mopping the gallery, was ordered to “hurry up and clean up the blood.” Officers warned him to keep quiet, Mr. Sanabria later told investigators.

Another inmate said Officer Rademacher had ordered him to clean up more blood from inside the office of the C Block hall captain, where guards had gathered after the beating. The inmate, Peter Thousand, said he had also been told to bring a bag of blood-soiled shirts to a courtyard where officers kept a barbecue pit. Prison officials later concluded that the shirts had been burned there.

The inmate witnesses told investigators something else: If the guards were looking to punish the prisoner who had shouted out the curses earlier that night, they had grabbed the wrong man.

To George Williams, the astonishing thing is that the charges of savagery and cover-up stemming from that hellish night have not been buried, but will be recounted in the weeks to come before a jury in the village of Warsaw, 14 miles from the prison

.

.

D cell

front gate

• George Williams Episode

The confrontation between George Williams and corrections officers occurred in C Block 1. After the officers beat him, he was taken to the solitary housing unit known as the Box 2. But the officer on duty there refused to accept Mr. Williams because of the severity of his injuries and sent him to the infirmary 3. The infirmary nurse deemed the injuries too severe to treat at the prison, and Mr. Williams was eventually taken to a hospital in Buffalo.

• 1971 Prison Uprising

The standoff began after inmates rioted while leaving the mess hall and brutally beat an officer at the intersection of the four prison tunnels, which is known as Times Square 1. Inmates and officers piled into D Yard 2 where hostages, including former corrections Officer Michael Smith, would be held. After four days, Officer Smith and other hostages were taken to a catwalk 3 and threatened with execution. Officer Smith was shot five times, but survived after several rounds of surgery. A memorial 4 to the officers and other prison employees who died stands in front of the prison.

A Violent Past

Attica Correctional Facility sits amid rolling hills of corn fields, tall silos and gambrel-roofed dairy barns. Residents like to say there are more cows than people in Wyoming County, although the heaviest concentration of humanity is the 2,240 inmates packed behind the great gray prison walls that measure more than a mile around and are topped by red-shingled turrets where armed guards stand watch.

Opened in 1931, the prison has long been the largest local employer. More than 600 officers patrol the prison today, all but a handful of them white. Meanwhile, 80 percent of the prisoners are black or Hispanic, almost half of them imported from New York City and its suburbs. The prison sustains the local economy. In all, it encompasses 1,000 acres, including a farm where inmates worked until budget cuts ended the program. Nearby is a cemetery where prisoners are buried when no one claims their remains. Older headstones carry no names, just identification numbers.

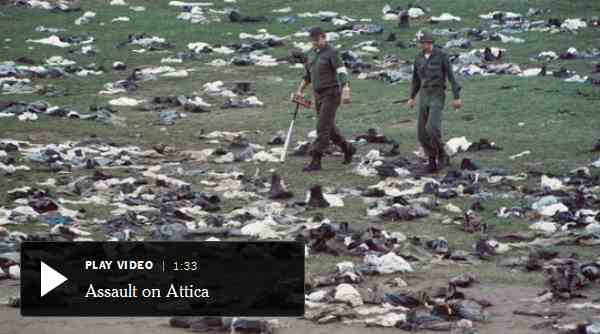

Looming over everything at Attica is the riot. The state commission that investigated the September 1971 uprising memorably described it as the bloodiest single encounter, Indian massacres aside, between Americans since the Civil War. Forty-three men died there, 89 more were wounded. Eleven of those killed were state workers, eight guards and three civilians. All but one had been held as hostages and died in a deadly hail of friendly fire after Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller ordered the authorities to retake the prison after a four-day standoff with mutinous inmates. One guard died two days earlier as a result of a beating inflicted by prisoners the day the riot erupted.

The rest of the victims were inmates. Twenty-nine were killed by police bullets fired in the Sept. 13 retaking of the prison. Three more were executed by other inmates during the takeover for actions deemed counter to the rebellion.

To those who work at the prison, the history of the riot is an everyday reminder of the danger that inmates, who greatly outnumber guards, could take over at any time. Mark Cunningham, an Attica sergeant whose father was killed in the retaking, tells all new recruits about the events of 1971. “I make sure it gets talked about,” Sergeant Cunningham said. “You do certain things a certain way because it wasn’t done one time and the inmates took control.”

Attica’s special tensions were long evident to Brian Fischer, who spent 35 years working in the state prison system, the last six as corrections commissioner, before he retired in 2013. “Attica has a unique personality, in part because of the riot,” Mr. Fischer said in an interview. “There’s an historical negativity if you will,” he added. “That doesn’t go away.”

Whatever the problems, the good pay and benefits that come with a job at a maximum-security prison like Attica are a trade-off for policing those serving the longest sentences for the worst crimes. “It’s the magna cum laude of prisons,” Richard Harcrow, an Attica guard for 31 years and former union president, said.

New York has 17 maximum security facilities, a constellation that sprawls from Sing Sing just north of New York City, to Clinton near the Canadian border, to Elmira, just north of Pennsylvania. They are often places of strife and violence, although most of what goes on remains shrouded from view both by remoteness and official secrecy.

The “unusual incident” involving George Williams in 2011 was initially recorded as just another time when officers were compelled to use force to defend themselves and do their jobs. There were 563 inmate assaults on prison employees recorded inside New York’s prison system that year, the vast majority in the maximum facilities. Over all, the state prison population has shrunk substantially in recent years, down 25 percent from a peak of 71,600 in the late 1990s when the Rockefeller drug laws sent thousands of men and women away to serve long sentences.

In January, the state had 53,000 prisoners in custody. The decline has allowed Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo to cut the total number of facilities to 54, from 67. But there are no plans to eliminate any of the maximum security prisons, which house 44 percent of New York’s inmates, said Anthony Annucci, the acting corrections commissioner.

Closings of any kind have been vigorously resisted by the New York State Correction Officers Police Benevolent Association, which represents the state’s 20,000 corrections officers. Partly, it is simple bread-and-butter unionism: Shutdowns mean lost jobs. Former Gov. Eliot Spitzer said he had encountered stiff union resistance when he tried to trim the state’s vast prison facilities. “Their political heft in districts where prisons were significant employers drove the opposition,” he said.

But recent closings, the union says, have led to inmate overcrowding and understaffing of guards, making their jobs far more dangerous. As proof, the union points to the recent rise in inmate assaults on staff, which reached 747 last year. In October, union leaders rallied outside Attica, where 85 cells meant to hold a single inmate are double-bunked. “Our officers have been stabbed and suffered compound fractures by inmates,” said Michael Powers, the current union president. “The state can’t continue to downplay the situation.”

State officials say what they call the “uptick” in inmate attacks is not linked to the closings, but have agreed to review staffing changes with the union.

The other uptick in prison violence is in the use of force by officers. While officials are supposed to track every time a body hold, baton strike, closed fist or chemical spray is employed by guards, inmates argue that does not always happen. Still, the number of recorded incidents rose by 25 percent between 2009 and 2013, with most of them taking place in the maximum security facilities.

Unlike Rikers Island, the huge New York City jail complex that has been roiled by revelations about the mistreatment of inmates in the past year, what occurs in the toughest state prisons has garnered little public notice. At Attica, most violent encounters between inmates and guards are handled internally. Charges are filed against the offender, a hearing is held and then a sentence is imposed, usually a hefty term in the Box. Inmates are invariably convicted. Of the 228 cases at Attica in which inmates were accused of assaulting corrections employees between 2010 and 2013, only one prisoner was found not guilty of all charges. Everyone else was sent to the Box for periods ranging from two to 16 months, records show.

These records were obtained by the Correctional Association, a 170-year-old nonprofit that monitors conditions in New York’s prisons. “It’s a kangaroo court,” said Jack Beck, the association’s project director, who has been inspecting New York prisons for more than 30 years.

Attica prison is surrounded by rolling hills of corn fields, tall silos and gambrel-roofed dairy barns. Residents like to say there are more cows than people in this section of western New York. Credit Chang W. Lee/The New York Times

An Inquiry Begins

Had the nurse on duty the night George Williams was beaten played down his injuries, he believes the episode would have been logged as one more inmate assault on staff members. “She was a blessing,” he said. “If she hadn’t of said I needed a surgeon, I would have been dead.”

Instead, Mr. Williams’s case took a very different route. The corrections department’s inspector general began an inquiry, and the State Police were soon called in as well. Over the following weeks, investigators asked guards, inmates and medical personnel what they had seen.

Many did not want to talk about it. Under their union contract, corrections officers are obligated to answer questions only from their employers and have the right to refuse to talk to outside police agencies. State Police investigators attempted to interview 15 guards; 11 declined to cooperate.

Inmates on C Block were reluctant to talk for their own reasons. More than two dozen said they had seen Mr. Williams marched past them and had later heard his screams. But those with the clearest view of what happened inside the dayroom balked at telling what they saw, saying they feared retaliation.

To get their stories, the State Police had the corrections department relocate five inmates to other prisons. Only after he was moved 100 miles east to Auburn Correctional Facility did Chris Tessitore recount how he had heard officers voicing anger at the curses screamed out that night. Mr. Tessitore said he had seen a guard aiming kicks at Mr. Williams on the floor but had averted his gaze when an officer looked in his direction. The screaming, he said, “went on for three to five minutes.”

An inmate named Alex Harris, who was relocated to Downstate Correctional Facility in Dutchess County, said that as he watched the beating, a guard had yelled to “get off the gates” — a command issued when officers do not want an audience. He said he had turned away to watch TV, but he still heard Mr. Williams pleading for his life.

A month after the beating, just as corrections officers and residents of the village of Attica were marking the anniversary of the 1971 riot, the corrections department issued formal “Notices of Discipline” to five officers. The notices sought their dismissal for using excessive force on Mr. Williams, submitting false documentation and lying to the inspector general.

The move prompted an immediate rebellion among Attica’s corrections officers, who began a by-the-book work slowdown. Such job actions are not uncommon, officials acknowledge, with the only victims being the inmates whose meals, programs and visitors are all delayed. The slowdown continued for several days until supervisors intervened. A few days later, after two fistfights among inmates in the yards, the entire prison was placed on lockdown. For five days, inmates were confined to their cells as officers conducted a prisonwide search for weapons. Union leaders later said that 60 weapons had been found, many of them in C Block — proof, they said, of the dangers the guards charged in the episode involving Mr. Williams faced.

Still, the investigations continued. On Dec. 13, 2011, a state grand jury in Warsaw handed up criminal indictments against four Attica guards: Sergeant Warner, along with Officers Rademacher, Swack and Erik Hibsch, who was accused of joining in the beating in the dayroom. The four were arraigned in State Supreme Court in Wyoming County on charges of first-degree gang assault, a law commonly used to help tame gangs like the Crips, Bloods and Latin Kings that thrive inside New York’s prisons. The charge carries a minimum sentence of eight and one-third years in prison and a maximum of 25 years. Additional felony counts accused the officers of filing false reports and tampering with evidence. The charges against Officer Hibsch were later dropped.

It was the first time, state officials said, that criminal charges had been brought against corrections officers for a nonsexual assault on an inmate.

Attica’s guards took the news as a direct attack on their ranks. Fund-raisers were organized for the indicted men. Blue ribbons — blue for the color of their uniforms and the symbolic “Blue Wall” of corrections solidarity — were printed with the slogan “Attica United.” A Facebook page was created. Donations flowed in from prison guards’ unions across the country. Inside Attica, the officers made another kind of statement: Doors decorated with inmates’ murals were repainted black, with a wide blue stripe across them.

Union leaders denounced the charges. “They did not go after this guy,” the union’s western regional representative, Al Mothershed, told a Rochester television station. “They did not beat him up intentionally. They used the amount of force that was necessary to gain control of this inmate and keep him from attaining a weapon.”

State corrections officials acknowledged in a statement that the department had referred the case to prosecutors, but stopped short of condemning the attack. The indictments, it said, were “troubling.”

The choice to refer the case to law enforcement was made by Mr. Fischer, the corrections commissioner at the time. “This was something too obvious to ignore,” he said. The “beat-down,” he added, was the worst such incident on his watch. “It was clear to me that a number of officers had acted together. It wasn’t something that spontaneously occurred, like in the middle of the hall.”

Mr. Williams was sitting in another prison dayroom when news of the arrests came on television. “I almost passed out,” he recalled.

Prisoners at Attica have long complained about being brutalized by corrections officers. During the 1971 uprising, inmates wearing cloaks and football helmets, some of them with makeshift weapons, waited to negotiate their demands with state officials. Credit Bob Schutz/Associated Press

Beatings Were ‘Normal’

Inmates at Attica were stunned by the indictments as well. To them, the remarkable thing about the beating Mr. Williams endured that August night was not the cynical way in which it seemed to have been planned, or even the horrific extent of his injuries. What was truly notable was that the story got out, and that officers had been arrested and charged.

“What they did? How they jumped that guy? That was normal,” said a prisoner who has spent more than 20 years inside Attica. “It happens all the time,” he said. That view was echoed in interviews with more than three dozen current and former Attica inmates, many of whom made the rounds of the state’s toughest prisons during their incarceration. They cited Attica as the most fearsome place they had been held, a facility where a small group of correction officers dole out harsh punishment largely with impunity. Those still confined there talked about it with trepidation. If quoted by name, retaliation was certain, they said.

Those now beyond the reach of the batons described life at Attica in detail. Antonio Yarbough, 39, spent 20 years in the prison after being convicted of a multiple murder of which he was exonerated in 2014. Unlike Mr. Williams, Mr. Yarbough could go head-to-head with the biggest of Attica’s guards: He is 6-foot-3 and 250 pounds. But he said that fear of those in charge was a constant. “You’re scared to go to the yard, scared to go to chow. You just stay in your house,” he said, using prison slang for a cell.

That fear was palpable to Soffiyah Elijah when she visited Attica a few months before the beating of Mr. Williams as the Correctional Association’s newly appointed executive director. The organization holds a unique right under state law that allows it to inspect state prisons. “What struck me when I walked the tiers of Attica was that every person, bar none, talked about how the guards were brutalizing them,” Ms. Elijah said. “There are atrocities as well at Clinton and Auburn, but the problem is systemic at Attica.” In 2012, the association began calling for Attica to be shut down. “I believe it’s beyond repair,” Ms. Elijah said.

Mr. Fischer, the former state corrections chief, reluctantly agreed with the conclusion that Attica should be closed. “Of all the maximum security prisons, I would probably argue, given the history of it, we’d probably be better off if we did,” he said.

Inmates say a minority of guards engage in brutality, but those who do exert a powerful influence throughout the prison. Officers viewed as too lenient often received warnings of their own. A common tactic used to punish inmates without having to file paperwork is to shut down power for a row of cells. “When the power goes off, nothing works,” one inmate explained. “The light goes off, the water won’t come out of the sink, the toilet won’t flush.” One officer who turned the power back on after a guard on an earlier shift had shut it down got a note left on his desk: “Inmate Lover,” it read, according to a prisoner who saw it.

Behind bars, where the grapevine is the chief source of news, stories can quickly grow exaggerated. Several prisoners said that Mr. Williams’s eye was knocked out of his head. That did not happen. But reports filed by guards often followed a script as well. Phrases like “removed his left hand from the wall, violently driving his elbow toward me” show up repeatedly in officers’ reports.

That is what happened, officers stated, on Jan. 21, 2011, when they pulled Sergio Barnes, a 33-year-old inmate from Rochester serving 25 years to life for murder and robbery, out of line for a frisk. Although surrounded by four guards, officers said Mr. Barnes wheeled around suddenly, punching one “in the face with both fists” and tackling another. In the melee that followed, he was slammed to the ground and struck multiple times with fists and batons.

Mr. Barnes was punished with 11 months in solitary confinement for assaulting staff members. He filed a prisoner grievance, but it was denied because he had no witnesses. The story of his encounter surfaced only because he filed suit in federal court, saying he had been beaten without cause. In his complaint, Mr. Barnes said that, after being frisked, a guard he later identified as Gary Pritchard Jr. slugged him in the eye, while others struck him in the head and body with their batons. Mr. Barnes said that after he had been shackled, guards rammed him face-first into a wall. “If you thought you were ugly before, look at your face now,” Mr. Barnes said Officer Pritchard taunted him, adding a racial slur.

Lawyers for the state moved to dismiss the lawsuit, but it was allowed to proceed and, in a rare victory for inmates who file motions themselves, Mr. Barnes later obtained a court-appointed attorney. Last October, the state, without admitting wrongdoing, agreed to pay Mr. Barnes $9,800 to settle the case.

In recent years, the state has settled several civil cases in which defendants in the Williams beating case were cited. One inmate was awarded $9,000 after accusing Officer Rademacher of pinning him against the wall and choking him while he was beaten by another guard. In September, the state paid $7,000 to settle a suit in which a C Block inmate claimed that guards wearing paper bags on their heads had sprayed him with a mix of vinegar, feces and machine oil in his cell. Among those the inmate cited were Officers Pritchard, Rademacher and Swack.

“You settle lawsuits for a lot of different reasons,” Mr. Annucci, the acting corrections chief, said when asked about the settlements. But he conceded that some guards pose problems. “Do I have rogue correction officers at Attica or Clinton or Great Meadow? Yep. Do I have to rigorously pursue those rogue officers when I find evidence that they’ve engaged in excessive force or have done something untoward to the inmate population? Absolutely.”

The surest way to catch officers using excessive force is on camera, but at Attica, there are few. Unlike most state maximum security facilities, the cameras are confined to the mess halls, the Box and — in a bid to catch drug smuggling — the visiting room.

Inmates have long sought cameras in the corridors, said James Conway, a former Attica superintendent whose father and uncle worked as guards at the prison. “They suspect there is physical abuse and the cameras will protect them,” said Mr. Conway, adding that he never had the money to install them. Pressed about Attica’s dearth of cameras, Mr. Annucci, the acting commissioner, said some 500 would be installed there this year.

Cases Against Guards

But even with evidence, officers can be difficult to fire. Consider the case of Gary Pritchard Jr., a legendary figure among both staff and inmates, and an example of just how hard it is to make changes in places like Attica. A corrections officer for 25 years, Officer Pritchard, 49, has worked at Attica since 1994. Last year, with overtime, he earned $128,000. Yet over his career, he has been named as a defendant in at least 24 federal civil rights lawsuits filed by inmates, some of which listed him by his nickname.

Testifying in federal court in January in an abuse case filed by a former inmate, Officer Gary Pritchard talks about his job and one of the tools of his trade. Read the full transcript.

“His jailhouse name was ‘Preacher,’ ” Rene Peterson, 61, who was imprisoned at Attica from 2000 to 2001, said in an interview. “Before he beat your ass, he want to say verses out of the Bible.”

David Anderson, 40, who was released from Attica in late 2013, also mentioned Officer Pritchard. “They call him Preacher because he’s got all kinds of Bible scriptures on him,” Mr. Anderson said. He cited Officer Pritchard’s alleged role in a group known to prisoners as “the Black Glove Crew.” It was a “beat-up squad,” he said, one that routinely doled out punishment to prisoners.

Prison officials say that the Black Glove Crew is an inmate myth. The name, they said, stems from the black, puncture-resistant gloves that officers were provided in the late 1990s to protect against infections. The authorities later replaced the black gloves with blue ones. But the stories lived on, fed by a stream of violent episodes involving glove-wearing guards in places like Attica’s C Block.

At least seven of the suits that name Officer Pritchard, who did not respond to telephone messages left with state and union officials as well as family members, have been settled by the state. In March, the state agreed to pay $6,000 to settle a suit by an inmate who said that while frisking him, Officer Pritchard had squeezed his testicles hard enough to make him cry, and had then beaten him brutally along with other guards, a claim mirrored in other lawsuits that date back to 1994.

State lawyers still opted to go to trial in January to contest a claim filed by a former inmate, who has since undergone gender reassignment surgery, who said that Officer Pritchard and other guards had beaten her while calling her a “freak.” Medical records showed that the former inmate, Brian Woodall, who is now Misty LaCroix, had a black eye and a broken rib. But the state’s lawyers said the injuries were most likely self-inflicted.

When Officer Pritchard took the witness stand in Federal District Court in Rochester, Ms. LaCroix’s lawyer asked him to show the jury the tattoos by which Ms. LaCroix had recognized him. The judge ordered him to comply. Officer Pritchard, a well-built man with a brush haircut, rolled up his sleeves, exposing drawings on both arms that included a skull, a knife, a spider, “Mom” and “Jesus,” and a phrase, “Angels All Around Me.” Asked if he routinely carried a baton, Officer Pritchard said, “I carry the biggest one they will give me.” He said that he had been present when the attack allegedly occurred, but denied there had been an altercation. After his testimony, a doctor testified that it would be almost physically impossible for Ms. LaCroix to have broken her own rib. Later that day, the state’s lawyers agreed to pay $80,000 to settle the case.

Despite what Mr. Annucci described as a “zero-tolerance policy for unacceptable behavior,” the corrections department has had difficulty reining in problem guards. Years before Officer Pritchard was accused of using fists and batons on Mr. Barnes, Ms. LaCroix and others, corrections officials had tried to fire him when he worked at Auburn in 1993. The union appealed his termination, and an arbitrator reduced the penalty to a one-month suspension.

Officer Pritchard then transferred to Attica. He did so, he said during a deposition in Ms. LaCroix’s case, because he considered it “the best facility in the state,” one with “an overall team spirit.” In 1997, administrators at Attica tried to fire him as well for beating an inmate. “I used my baton with everything I had,” Officer Pritchard said in his deposition, delivering a blow “that resulted in a couple of missing teeth.” He had done nothing improper, he said. An arbitrator disagreed but kept his punishment to a $1,500 fine.

In one suit that is still active, state officials acknowledged that the corrections department’s inspector general had investigated 26 separate complaints against Officer Pritchard between 2001 and 2007, without bringing charges against him.

Between 2009 and 2013, the corrections department did bring charges against other officers 190 times for abuses of inmates at various prisons around the state, according to records obtained by the Correctional Association. Most of those cases were settled. In the 25 cases arbitrators heard involving the alleged abuse of inmates, only six officers were ordered terminated, primarily for having improper relationships with inmates.

In a 2012 case, the department tried to fire an officer accused of having struck an inmate “35 times with a baton, then twice more after he was handcuffed,” and then filing a false report about the confrontation. An arbitrator ordered a seven-month suspension.

The department’s negotiated settlements are often mild as well. Five correction officers charged in 2011 with using force on a shackled inmate and then lying about it to the inspector general were allowed to resolve the matter by paying fines ranging of $1,800 to $3,000. The specifics of these disciplinary cases are another secret of the state prison system. Under New York’s civil rights law, personnel records for corrections officers (as well as for many police and fire departments) are deemed confidential and “not subject to inspection or review.” Individual records like Officer Pritchard’s emerge only when subpoenaed in lawsuits, and then are usually kept under seal.

Even when it comes to deciding where officers should work, prison administrators have little leverage. James Conway, the former Attica superintendent, said he had tried at one point to get Officer Pritchard into a job where he did not interact with inmates. But under the officers’ union contract, Officer Pritchard did not have to give up his post. Officers choose their job assignments based on seniority, and Officer Pritchard had won his job by bidding for the position.

“He develops his own little posse in C Block,” Mr. Conway said. “The younger officers would look up to him because he had this reputation of being a tough guy, a by-the-book guy.”

Inmates at Attica shouted their demands during a negotiating session with state corrections officials in September 1971. Credit Associated Press

A Deadly Riot

In September, Mr. Annucci became the first commissioner to attend the annual memorial ceremony at Attica for corrections workers killed in the riot. “Time does not heal all wounds,” he told the small crowd. “Certain wounds and scars went too deep to ever heal.”

It was a simple and somber event held on a grassy plain outside the arched, gothic doors of the prison’s main entrance. There was an honor guard of corrections officers, a bugler playing taps and an a cappella rendition of “Amazing Grace.” The center of attention was a tall granite marker that listed the names of the 11 prison employees who died. The 32 dead inmates were unmentioned, their names nowhere to be found inside or outside the prison. The reason, several participants in the ceremony said, was simple: The inmates caused the riot.

Michael Smith, a former corrections officer who was one of those taken hostage during the standoff, saw it somewhat differently. Mr. Smith was 22 at the time of the riot and had been at Attica for just a year. He got along with most inmates, he said as he sat in his living room 30 miles south of the prison. “I treated everyone respectfully and I expected to be treated with respect in exchange.” But tensions had built throughout summer 1971. “You could just feel it,” he said.

A few weeks before the riot, two inmates showed him a letter they had drafted to send to the corrections commissioner at the time, Russell Oswald, and Governor Rockefeller. “They wanted better education, more religious freedoms and more than one roll of toilet paper a month,” Mr. Smith said.

On Sept. 8, officers mistook a pair of sparring inmates for a serious fight. It proved the riot’s spark. When guards tried to take the men to the Box, prisoners began to throw cans. The next morning, inmates who were returning from the mess hall erupted at Times Square, as the intersection of the prison’s four tunnels is called, fatally beating Officer William Quinn, 28, a father of three girls. Mr. Smith was guarding men in the metal shop when the siren wailed. Within minutes, a surge of rampaging inmates had burst inside. Mr. Smith was knocked to the floor and kicked repeatedly until a pair of inmates intervened. They led him out, through a prison that was spiraling into chaos. “They were lighting anything that would burn, beating up anyone who was administration,” he said.

At Times Square, other prisoners grabbed Mr. Smith, taking him and 37 other hostages to D Yard. Prisoners were gathering weapons, he said, “clubs, hammers, baseball bats, knives.” A group of Muslim inmates became the hostages’ protectors. Blindfolded, they heard speeches over the next two days by inmate leaders and outside observers summoned by the rebels, including the radical lawyer William M. Kunstler; Bobby Seale, the chairman of the Black Panther Party; and State Assemblyman Arthur Eve of Buffalo. The inmates issued a list of demands, many of them from the letter Mr. Smith had seen. Added to the list was amnesty. Officer Quinn’s death was a deal-breaker.

On Sunday, his third day as a hostage, Mr. Smith was interviewed by a television crew that had been allowed into the yard. He called for Governor Rockefeller, who had refused to come to Attica, to “get his ass here now.”

By then, the governor had decided to end the standoff. On Monday morning, under an ominous sky, Mr. Oswald, the corrections commissioner, issued an ultimatum to the prisoners. The inmates responded by grabbing eight hostages at random, including Mr. Smith, taking them to a catwalk above the yard and threatening to execute them. Mr. Smith was seated in a chair, surrounded by three men armed with a hammer, a spear and a knife. He realized that one of the armed men was Don Noble, an author of the letter to the governor. A helicopter made two low passes overhead, followed by a popping sound as a gas was dropped into the yard. Gunfire erupted. “All hell broke loose,” Mr. Smith said.

In a hail of gunfire, the New York State Police regained control of Attica Correctional Facility on Sept. 13, 1971, ending a four-day prisoner revolt. Forty-three people died.

Publish Date February 28, 2015. Photo by Associated Press.

State troopers armed with rifles and shotguns did most of the shooting, but corrections officers fired as well, despite being ordered not to. As bullets whizzed past, Mr. Smith felt Mr. Noble yank him off the chair. Mr. Smith believes the action saved his life, but he was still struck by five bullets, four of them from an AR-15 automatic rifle. The gunman, he is sure, was a fellow corrections officer who had gotten the weapon from the prison arsenal and had mistaken him for an inmate.

He lay on the catwalk, unable to move as the firing continued. “It seemed like it was going on forever,” he said. Later, an ambulance took him to a hospital in nearby Batavia, where he had multiple operations over the next six months.

Shortly after the clouds of gas lifted, a state official said that the slain hostages had died from slashed throats. Michael Smith, the official said, had had his testicles severed and stuffed in his mouth. None of it was true. Two hostages suffered severe cuts from would-be executioners, but the wounds were not fatal. Autopsies performed by medical examiners confirmed that gunshot wounds were the cause of death in all of the hostage fatalities. And none of the inmates had guns.

Still, the vivid pronouncement by the authorities stuck in many minds. Deanne Quinn Miller, whose father, William, was the riot’s first victim and who, with Michael Smith, helped found a group called Forgotten Victims of Attica, said that many residents continued to believe the stories. “You can’t have that conversation with them,” she said. “It’s what they’ve decided.”

Lingering Pain

For many years, inmates observed Sept. 13 by sitting in silence at breakfast in the mess hall. Sometimes there would be a slow, dirgelike drumming of spoons. But the protests gradually faded away. “Either they don’t know, or they’re scared,” one Attica inmate said.

George Williams knew about Attica’s history but had not concerned himself with it. “I wasn’t there for that,” he said during an interview in November in a New Brunswick restaurant. Now 32, he is a good-looking man, with a broad face, wavy, close-cropped hair and a bright smile. As he talked, he dabbed steadily at his nose, a residual effect of the sinus damage from the beating three years ago. Other mementos included a left eye more sunken than the right, and a leg that, he said, “is always bothering me.” Less visible are the headaches and nightmares. “I still can’t sleep,” he said.

After he was released from the hospital, Mr. Williams was sent to a different maximum security prison, near Buffalo. He finished his sentence in January 2012 but was soon behind bars again, in New Jersey, for a probation violation. Doctors there said he had post-traumatic stress disorder after he described flashbacks and waking from nightmares in a sweat.

He still does not know why he was singled out at Attica. “I was doing my time,” he said. “I was ready to go.” He was released from jail in New Jersey just before Thanksgiving. His crimes, he said, were a product of being “young and dumb.” In the hospital, he worried that if he died, his family would assume it was “because of something I did.”

Photo

George Williams, a former Attica inmate whose claims of being brutally beaten at the prison in 2011 are the basis of the criminal case against three corrections officers who are set to go on trial Monday. Credit Damon Winter/The New York Times

Mr. Williams is now trying to raise money for barbering school tuition. Of the criminal case against the Attica guards, he expressed wonder that it was still active. “I don’t want it to be a cliché, but I just hope that justice is served,” he said. “That’s it.”

The trial is scheduled to begin on Monday. The defendants — Sergeant Warner and Officers Rademacher and Swack — have retained some of western New York’s top criminal defense lawyers, thanks in part to help from fellow officers. The fourth guard, Officer Hibsch, was given immunity to testify, but lawyers for the defendants have indicated that they are not concerned with his testimony. “There were all kinds of plea offers,” Norman Effman, who represents Officer Rademacher, said. “Our clients could walk away if they were willing to resign their jobs. They maintain their innocence; they did nothing wrong.”

Officer Hibsch returned to work at Attica after an arbitrator ruled in May that his use of force in the dayroom on the day that Mr. Williams was beaten was “not unjustified.” After hearing from 39 witnesses, including Mr. Williams and several other C Block inmates, the arbitrator ordered Mr. Hibsch reinstated with back pay. Corrections officials said that, as a personnel matter, they could not discuss the decision.

Inmates still incarcerated at Attica said there were high hopes that the case would spur changes in how the prison was policed. Those hopes have since ebbed. The only way to get attention, they said, is something dramatic. “We feel Albany doesn’t give a damn,” one inmate said, voicing despair rather than menace. “No one on the outside is going to change anything. Guys say: ‘We need a riot. It’s the only way to stop it.’ ”

This article is by Tom Robbins of The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization that focuses on criminal justice issues.

A version of this article appears in print on March 1, 2015, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: A Brutal Beating Wakes Attica’s Ghosts.

Spread the word