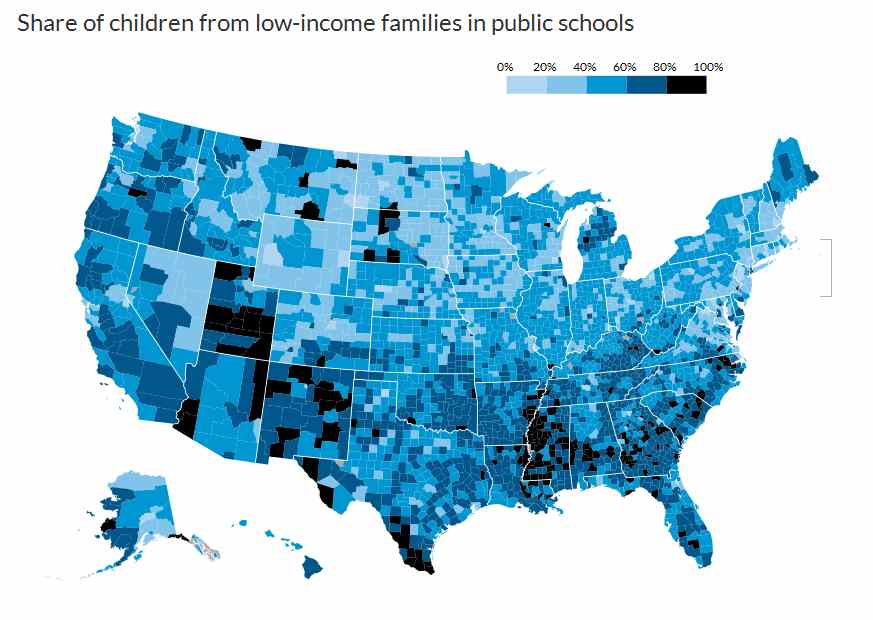

A majority of public school students nationwide are from low-income families, according to analysis by the Southern Education Foundation. But mapping this disadvantage shows that it’s unevenly spread across the country: poverty is concentrated in specific schools, and black students are more likely than white students to attend these high-poverty schools.

The foundation’s report tracks student poverty through eligibility for free and reduced-price lunches, which are available to students with family incomes at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level. Although eligibility for such programs is an imperfect measure for poverty, it is often used by federal agencies as a close proxy. About 33 percent of public school students in 1995 and about 38 percent in 2000 were from low-income families. But, for the first time since the beginning of tracking, the share surged to over 50 percent in 2013, after the Great Recession.

A small share of this increase may be attributed to changes in enrollment rules and program eligibility, but evidence suggests that rising child poverty and economic instability and, perhaps, increased immigration are the primary drivers of this change.

If our school systems continue on a trajectory of increasing poverty, they will face mounting challenges educating students. What’s more, students of color will continue to face setbacks from the disadvantages of high-poverty schools, while white students will continue to benefit from a legacy of discrimination that largely insulates them from high-poverty schools. Public policy can and should respond, but policymakers need a more nuanced understanding of how this increase is playing out in local areas.

Southern states like Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas have the highest levels of students in low-income families attending public schools. But state-level estimates can hide important patterns. For example, a closer look reveals that large shares of low-income areas in the South are often rural. In many rural parts of Kentucky (such as Jackson, Owsley, and Clay Counties), 60 percent or more of all students are from low-income families. A similar belt of rural poverty stretches across Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.

Scroll over the map to see the share of students in low-income families in schools within a particular county. Sometimes counties and school districts are identical, but some counties contain multiple school districts. Unlike many school districts, however, counties are usually meaningful geographies for citizens and policymakers.

Some major southern metropolitan regions that include suburban and urban areas also have high numbers of students from low-income families. In the greater Dallas area, the share is over 70 percent; in Harris County, Texas, which includes most of metropolitan Houston, the share is about 66 percent .

In northern states, where the overall rate is lower, we find more students in low-income families in metropolitan areas, like Minneapolis (Hennepin County) and Indianapolis (Marion County), and in Native American areas, like the Lakota region of South Dakota.

South Dakota is an example of how poverty varies by place, even within states. The state’s share of students in low-income families is about 40 percent, but the shares in the Lakota counties of Shannon, Todd, and Ziebach are close to 100 percent. These alarming rates are certainly worthy of policy attention, yet they are obscured in state-level estimates.

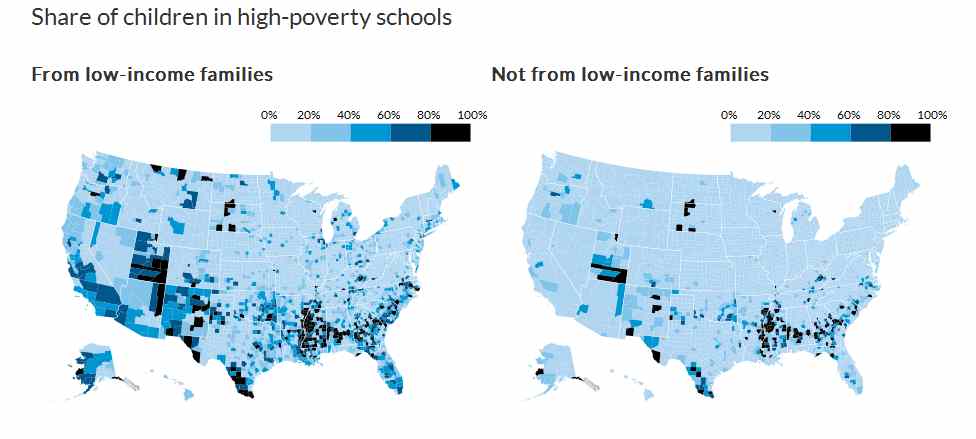

Poverty is highly concentrated in public schools, meaning that a student in a low-income family is very likely to be in a school with other students in low-income families. And if a student is not in a low-income family, most of his or her classmates are also likely not in low-income families.

Nationwide about 40 percent of students in low-income families (10 million) attend high-poverty schools, where more than 75 percent of students come from low-income families. Only about 6 percent of students in low-income families attend low-poverty schools, where less than 25 percent of students come from low-income families. So, students in low-income families are over six times more likely to attend a high-poverty school.

The pattern is reversed for students who are not in low-income families. Only about 6 percent attend high-poverty schools, while about 37 percent attend low-poverty schools.

Students from Low-Income Families Are More Likely to Attend High-Poverty Schools

Why should we be concerned about concentrated poverty? Because high-poverty schools tend to lack the educational resources—like highly qualified and experienced teachers, low student-teacher ratios, college prerequisite and advanced placement courses, and extracurricular activities—available in low-poverty schools. These inequitable educational offerings are compounded by the toll of poverty itself on the physical and psychological development of children. As a result, high-poverty schools are tasked with a tremendous load and are often unable to provide either the quality of education or the additional resources and supports needed to help students in low-income families succeed. This is concentrated disadvantage: the children who need the most are concentrated in schools least likely to have the resources to meet those needs.

Although concentrated poverty is a national phenomenon, areas of the South, Southwest, and metropolitan Midwest and Northeast tend to have extreme levels of concentration. In Oklahoma County, for example, 67 percent of students in low-income families attend high-poverty schools compared with 12 percent of students not in low-income families. Fresno County also has incredibly concentrated poverty: over 75 percent of students in low-income families are in high-poverty schools, compared with less than 20 percent of their not-low-income counterparts.

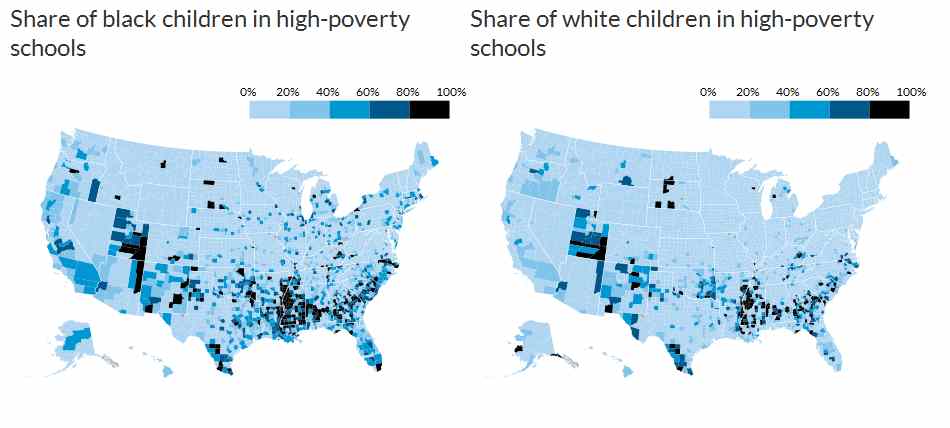

Race has profound importance in school poverty. Research has documented decades of public policy and private action that systematically exclude people of color—especially black people—from good neighborhoods, jobs, and wealth-building opportunities. Those same policies created and perpetuate poor, racially segregated communities and schools, resulting in students of color disproportionately experiencing poverty concentration.

So white students’ public school experiences are most often characterized by attending a low-poverty school, while black students experience incredible levels of concentrated poverty in both their schools and their neighborhoods.

Nationally, about 30 percent of white students attend low-poverty schools, while only 8 percent attend high-poverty schools. In other words, white students are about four times more likely to attend low-poverty schools than high-poverty schools. The pattern is flipped for black students, for whom attending high-poverty schools is commonplace. Over 45 percent of black students (about 3.4 million) attend high-poverty schools, and only about 7 percent attend low-poverty schools. This means that black students are over six times more likely to attend high-poverty schools than low-poverty schools and about six times more likely than white students to attend high-poverty schools.

Black Students Are Far More Likely to Attend High-Poverty Schools

In some metropolitan areas, the racial concentration of school poverty is so severe that black and white students effectively attend two different school systems: one for middle- and upper-middle-income white students, and the other for poor students and students of color.

This is certainly true in Chicago (Cook County), where 75 percent of black students attend high-poverty schools compared with less than 10 percent of white students. The same dual system exists for the 75 percent of black students (40,000) in Milwaukee who attend high-poverty schools compared with 10 percent of their white peers.

In fact, racial inequity is a defining feature of almost all midwestern and northeastern metropolitan school systems. In greater Minneapolis (Hennepin County), almost 50 percent of black students attend high-poverty schools compared with only 4 percent of white students. Across the river, 53 percent of black students in the St. Paul area (Ramsey County) are in high-poverty schools compared with 9 percent of white students. In these communities, black and white children living relatively close to one another attend what amounts to different worlds of schooling.

Are low-income white students less likely to attend high-poverty schools than low-income black students? The national data do not allow us to answer this important question. Yet research shows that the discriminatory policies and practices creating poor, segregated neighborhoods and schools cut across class lines. Blacks of all socioeconomic classes live in higher-poverty neighborhoods than whites of similar income. Because blacks of all classes are more likely to live in high-poverty neighborhoods, we can expect to find black students attending poor, segregated schools wherever students are assigned to neighborhood schools.

Policy solutions for addressing school poverty

Potential solutions exist within both school and housing policy, because schools and neighborhoods are intimately linked. Neighborhood segregation, a powerful driver of racial inequality, is commonly responsible for high-poverty schools. Local context will determine the specific solution, but proven remedies are widely available, are fiscally feasible, and use various housing and school policy levers.

Housing programs can alleviate the concentration of race and poverty in schools. Promising initiatives include mobility programs with information for parents on neighborhood and school quality, rigorous enforcement of fair housing policies, and help locating affordable housing in low-poverty neighborhoods with access to better schools.

For example, Montgomery County, Maryland’s innovative and decades-long inclusionary zoning policy requires large-scale housing developers to set aside 12 to 15 percent of homes for affordable housing. As a result, affordable housing is scattered throughout the affluent county. Students in low-income families living in these affordable units benefit from both living in low-poverty neighborhoods and attending low-poverty schools. Over time, these children have performed better academically.

Region-wide school policymakers can also recognize that poor, racially isolated schools and neighborhoods are damaging to regions as a whole because the health of cities and their suburbs are closely intertwined. Policymakers could redraw school district boundaries (which often reinforce inequality) to cross suburban and city lines or encourage resource-rich suburban schools to accept low-income transfers.

One such program is the Minneapolis metropolitan region’s decade-long Choice is Yours initiative, which allowed students from low-income families enrolled in the city's schools to transfer to a nearby suburban school district. Through enhanced state funding that followed the transfer student, low-poverty suburban schools were motivated to participate in the program. Though the program is now inactive, participating students made significant and sustained academic improvements.

One of the country’s most successful and ongoing school desegregation initiatives in Louisville, Kentucky, shows that thoughtfully designed and implemented metropolitan-wide school desegregation continues to serve as a highly effective tool to create racially and socioeconomically diverse schools, improve outcomes for children in low-income families, and stabilize local housing markets and regional tax bases. After the Supreme Court struck down Louisville’s voluntary desegregation program in 2006, the school system—backed by support and buy-in from white and black families—revised the program in an effort to maintain diverse schools.

To generate opportunity and social mobility for all students, the public school system needs to provide the same quality of education for students of color and poor students as it does for white students. But our school system alone can’t solve the problem. We have the policy tools—in both housing and schools—backed by solid research to address concentrated poverty. Doing so is imperative for our children, our schools, and our neighborhoods and cities.

Spread the word