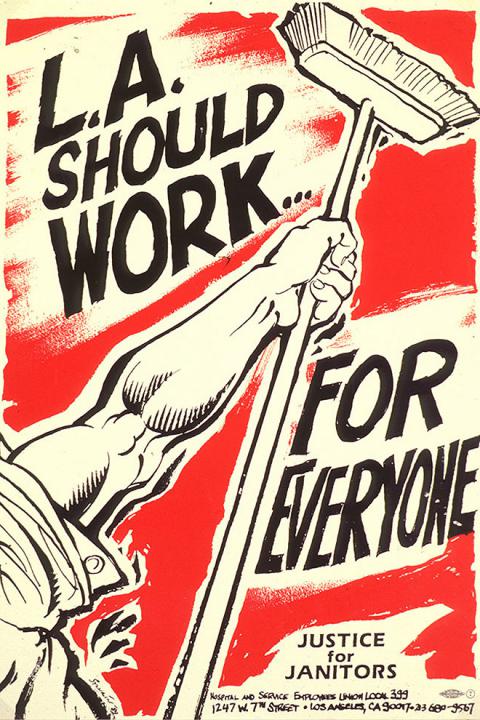

The article Justice for Janitors: A Misunderstood Success makes some excellent points, and shows the importance of the way the existing base of membership was used to reorganize building services and start Justice for Janitors. Its point about the market triggers was very interesting – I hadn’t really heard this discussed before, and it does show that putting this in the contract gave workers a concrete reason to support reorganizing the non-union buildings. As it says, ” it was not a ‘blank slate’ campaign disconnected from the sources of SEIU’s membership and contract power.” [response to original article, which was re-posted by Portside Labor last Monday.]

Many of the janitors and leaders who fought in Century City were the Central American immigrants coming into LA from the wars. Their experience in their home countries was very important in their willingness to fight, and the use of the tactics of mass demonstrations and even CD in the street. They’re one of the best examples of the way migration, for all the pain it causes migrants, has benefited our labor movement enormously and given us leaders from Rocio Saenz to Ana Martinez to Yanira Merino. This is a big reason why there was an upsurge of organizing in general in LA in the 90s. Without this wave of migration I don’t think the best of strategies would have produced the results we saw. The article credits Gus Bevona with a role in getting the contract in Century City, but by comparison, this seems less important to me, and more like the mechanism than what actually forced the contractors to settle.

Because of the often left-wing ideas of these migrants about how unions should function and their expectations that the union they were fighting for would be responsive to the base, there was a collision in Local 399 that we all remember. That’s an important lesson too – we’re organizing unions (not just mobilizing workers), and they have to be vehicles for the workers who come in for a real fight with the boss to change conditions. When they’re not, or when workers who’ve been in the streets get shut out of power, there can be a big conflict, as there was here. This continued to be a question after the contracts were signed — how much control did workers have, and how big were the gains in economic terms.

The conflict continued over immigration policy. When the contractors and government covertly collaborated in firing janitors a decade later for not having papers, this contradiction became very sharp. SEIU was lobbying for immigration reform bills in Washington DC that included increased enforcement of employer sanctions, while janitors in LA were losing their jobs to this enforcement by the hundreds. Any desire for an all-out fight for the jobs of workers had to contend with a national decision to support enforcement bills. What was then USWW in LA, Sacramento and San Jose did organize marches to protest the firings, which is more than many unions have done. And Latino members of SEIU’s International Executive Board even voted against the early endorsement of Obama in 2012 because they couldn’t stomach endorsing him while their members were being fired at the direction of the Department of Homeland Security. This basic contradiction, not just in SEIU but in other unions too, is the main reason why we didn’t have a broad militant campaign across the country to stop the wave of firings that by now has affected tens of thousands of families.

JfJ highlighted the strategy of the building owners and contractors to shed a largely unionized African-American workforce and replace it with (what they thought would be) docile immigrants. Big miscalculation on their part. It dramatized the reality of the way our system pits workers against each other, often along race lines, and therefore raises the question of how workers and unions need to respond. The big lesson on this one wasn’t the janitors, but the hotel workers in San Francisco. They began negotiating contracts that combined language protecting the rights of immigrant members with hiring language forcing hotels to take down the color line against hiring African Americans. I was told at one point that USWW planned to do the same with janitors in LA, but I don’t know if this happened. The local now includes a building service division and a security division, and my impression is that one is largely Latino and the other largely African American.

Although Bread and Roses does show that the LA janitors were immigrants (not just Latinos), it treats them as followers of an organizer, who’s the one with the strategy and ideas. I thought this was more than a little patronizing. And I don’t remember the movie showing anything at all about the division between immigrants and African Americans, and the transformation of the workforce before the campaign started. Many writers, myself included, have looked at the role of migration in the LA upsurge. Most, however, do what so many mainstream writers do when they write about labor. The workers are illustrations. They talk about their experience, but the analysis and strategy come from academics, organizers, and especially from the writers. I think its much more interesting, and important for left wing organizers and activists, to understand the way workers themselves analyze their own experience and draw lessons from it. The janitors’ experience in Los Angeles should be one of the most important places where we hear that.

David Bacon

David Bacon is author of Illegal People—How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants, and the forthcoming The Right to Stay Home, both from Beacon Press.

The Stansbury Forum is a website for discussion by writers, activists and scholars on the topics that Jeff focused his life on: labor, politics, immigration, the environment, and world affairs.

Spread the word