Last week, Southerners and South-watchers looked on in amazement as the Confederate flag and other symbols of the region's embattled past were denounced and, in places like the Alabama capitol and South Carolina's Fort Sumter, removed entirely in the wake of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church massacre in Charleston.

Of the 10 states where drivers can order a specialty Confederate license plate, lawmakers in four of them — Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia — have called to stop issuing the plates or to revisit the designs. Leading national politicians have come out against the flag, including all of the Democratic presidential hopefuls and, after some foot-dragging, Republicans including Jeb Bush and Rand Paul.

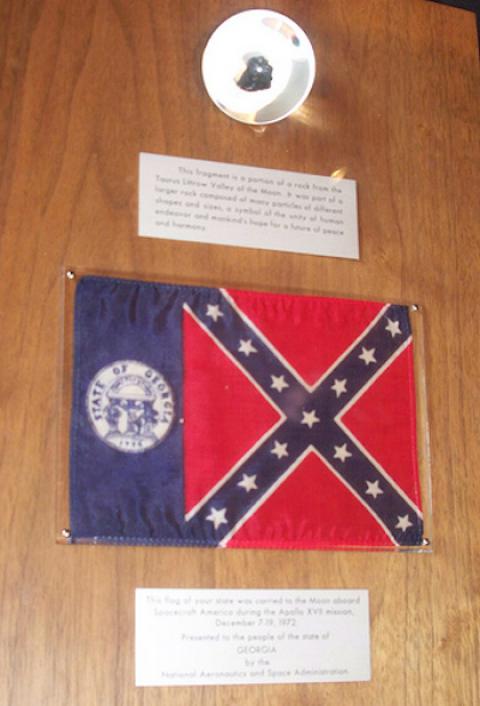

It was a whirlwind week of media and political controversy. But will the push to rethink the Confederate flag and other Old South symbols that dot the Southern landscape continue once the TV crews leave? After all, Southern states faced a wave of protests over the flag in the early 1990s and early 2000s that led South Carolina to move its Confederate flag from the capitol dome to the statehouse grounds and Georgia to revise its state flag, but nothing more.

This time, however, there are two key differences in the Confederate symbolism debate: economics and politics.

In the wake of the Charleston tragedy, retail giants Amazon, eBay, Sears, Target and Walmart all announced they would immediately stop selling Confederate-themed merchandise. For years, state economic development officials had complained that Confederate imagery hurt their efforts to recruit businesses to the South, especially international companies.

After ordering the flag to come down in Alabama, Gov. Robert Bentley (R) announced a new Google facility was opening in the state, and noted that the flag was "not worth a job."

By far the most important company to take a stand, however, was NASCAR, the multibillion-dollar sport that grew out of the South and where Confederate flags are commonplace from track infields to parking lot tailgates. CEO Bill Nance — the grandson of founder Bill Nance Sr., who in 1968 campaigned for arch-segregationist George Wallace — announced the flag would no longer be welcome at NASCAR events, stating:

We will be as aggressive as possible to disassociate NASCAR events from an offensive and divisive symbol. We are working with the industry right now to achieve that goal.

Nance got backup from leading NASCAR racers Jeff Gordon and Dale Earnhardt Jr., who said of the Confederate flag, "It's offensive to an entire race." At its upcoming headliner race in Daytona, NASCAR is offering to trade fans a U.S. flag in exchange for Confederate ones.

While NASCAR leaders can take the moral high ground, the decision is also being made out of economic necessity. After peaking in national popularity in the mid-2000s, NASCAR's fan base has been steadily shrinking, forcing executives to figure out how to gain new fans, including a more racially diverse younger generation.

Changing demographics are also a key backdrop for the sudden rejection of Confederate symbols among Southern politicians. The South is at the forefront of demographic shifts that are happening across the country. Over the last decade, Southern states have ranked near the top in the growth of Asian and Latino communities. African-American return migration, a reversal of the Great Migration a century ago, is fueling a growth in black communities, especially in cities. The share of residents in the South who are newcomers from other states and countries is on the rise.

These demographic shifts mean a changing electorate in the South, making it increasingly untenable for lawmakers — especially those with long-term political ambitions — to champion the Old South cause.

The tragedy in Charleston brought this transformation into sharp relief, especially in South Carolina. While it rarely makes pundits' lists of top battleground states, South Carolina has had the fastest-growing Latino population in the country between 2000 and 2012. More than two-thirds of the state's growth — which helped South Carolina gain an extra congressional seat after the 2010 Census — came from newcomers to the state. More than a third of residents in the state were born outside the state, and more than 20 percent are from outside the South.

South Carolina still hasn't removed the Confederate flag flying on its capitol grounds, which inspired North Carolina activist Bree Newsome to scale the flagpole and briefly remove it herself last weekend. BMW, Boeing, Michelin and Sonoco have called for the flag to come down, and media surveys of legislators show more than two-thirds of members of the state House and Senate have announced they plan to vote in favor of removing it.

In short, change, or at least this one symbol of change, will likely come. But the political and economic calculations at play in the removal of Confederate symbols — combined with the amount of time it's taken Southern leaders to address the issue — lead to the suspicion that the recent anti-Confederate outcry doesn't reflect broader changes in the South's political culture. As Dr. James Cobb, professor of history at the University of Georgia, told the Associated Press:

I don't think we need to be handing out huge medals to Haley and others who are sort of following suit. In the context of the South's history, I suppose it's a watershed. But it would have been easier to celebrate it as a watershed 20 or 30 years ago.

It also remains to be seen how far-reaching the changes will be. Supporters of the Confederate flag are rallying to its defense. Public opinion is still divided: Recent surveys by CNN and USA Today find that that most whites think the Confederate flag is simply an expression of Southern heritage, while an overwhelming majority of African Americans unsurprisingly see it as a symbol of racism.

Others have called the flag a distraction from "real" issues like poverty, housing discrimination and other concrete forms of inequality. But as Ed Sebesta — a Dallas-based researcher who has been following the neo-Confederate movement for more than two decades — argues, the South's flags and symbols are powerful in shaping the ideas of Southerners and transmitting views of racism and inequality from generation to generation.

While the recent uprising against Confederate symbols is a welcome development, Sebesta believes it will likely be a long-term battle to thoroughly uproot these artifacts, and the ideas they represent, from Southern life. As Sebesta, who is co-author of the seminal book "The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader," wrote this week in the Black Commentator:

The power of the neo-Confederate movement is through the shaping of identity and values ... Once Jefferson Davis is your hero and the plantation is your ideal, whether conscious or not, you will naturally support the politics of inequality.

hough recent events are very encouraging and will represent real progress in fighting the neo-Confederacy, there is a long struggle ahead and a lot will depend on people realizing this is important and affects the real issues of the day.

[Chris Kromm writes for Facing South, the Online Magazine of the Institute for Southern Studies.]

Spread the word