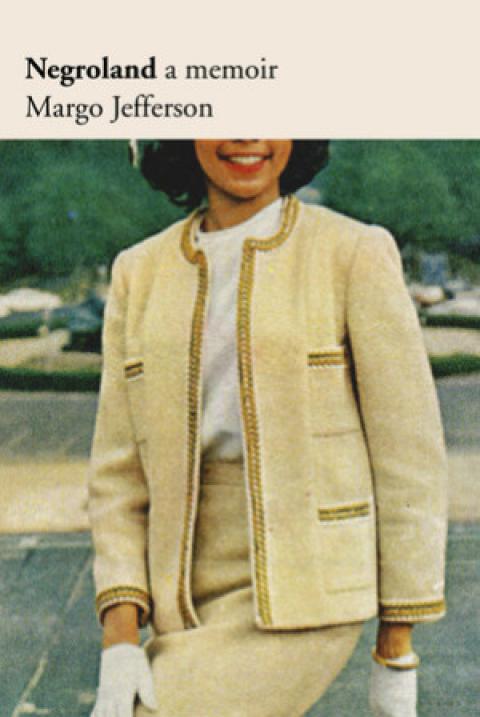

Negroland

Margo Jefferson

Pantheon Books

ISBN: 978-0307378453

Margo Jefferson's book Negroland describes her experiences growing up well-educated and affluent, but also suffering from racism and shouldering all the burdens of being a girl and young woman in mid- to late-twentieth-century America. This book is not only a memoir, though; it is also the story of other people like Jefferson at earlier points in American history, other members of "Negroland," which she defines as "a small region of Negro America where residents are sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty." She goes on to explain:

Children in Negroland were warned that few Negroes enjoyed privilege or plenty and that most whites would be glad to see them returned to indigence, deference, and subservience. Children there were taught that most other Negroes ought to be emulating us when too many of them (out of envy or ignorance) went on behaving in ways that encouraged racial prejudice.

This is one of the central tensions of the book: Members of "Negroland" are at odds not only with white culture but also with much of black culture, and they think of themselves, as Jefferson writes, "as the Third Race, poised between the masses of Negroes and all classes of Caucasians."

Early sections of the book take us through a history of African American writers, thinkers, reformers, and activists who wanted to improve the lot of their fellow African Americans while at times distancing themselves from members of the lower classes. We meet, for example, Joseph Willson, born in 1841 and son of a wealthy middle-aged slaveholder and a teenage slave, who wrote Sketches of the Higher Classes of Colored Society. This book, Jefferson argues, sets the tone for others who wrote on the subject as it tries to assert and defend the presence of higher-class African Americans to a skeptical white audience. We learn about Cyprian Clamorgan who published The Colored Aristocracy of St. Louis and set himself up as a cataloger of the upper classes and an arbiter of taste, and Charlotte Forten, an essayist and reformer from a distinguished Philadelphia family, who worked for abolition and to improve education for the poor but who still displayed hints of class snobbery. It is from this culture that later, better-known writers such as Ida B. Wells and W. E. B. Du Bois emerge, each with their own ambitions to improve the lives of poor African Americans and a belief that, as Jefferson attributes to Du Bois, "he educated and privileged must guide the Mass of Negroes forward."

This is interesting history in and of itself, but its inclusion also serves another purpose. Childhood warnings against showing off linger in Jefferson's mind, and the history allows her to tell her personal story while avoiding an unladylike, potentially threatening display of her abilities. The book opens with this dilemma:

I was taught to avoid showing off.

I was taught to distinguish myself through presentation, not declaration, to excel through deeds and manners, not showing off.

But isn't all memoir a form of showing off?

In my Negroland childhood, this was a perilous business.

And so she makes the book a cultural history as well as a memoir, a story of her race and class as well as a personal tale. Her own chapter in this larger story begins in 1947 in Chicago where she and her sister grow up with a father who is a prominent doctor and a mother who is a socialite. The girls attend prestigious (mostly white) schools and participate in clubs that teach them proper behavior. Margo loves poetry and drama and acts in plays when she can. They move into nicer, higher-status neighborhoods. It is a comfortable childhood. And yet Margo always has questions about how she fits in. She asks her mother, "Are we rich?" and then, "Are we upper class?" The answer comes: "'We're considered upper-class Negroes and upper-middle-class Americans,' Mother says. 'But most people would like to consider us Just More Negroes.'"

People ask her whether she knows the school janitor and whether she has "Indian blood." She is asked to help another African American child fit in at camp, even though the two children have nothing in common. The family is told while on vacation that their hotel reservation was lost. Their white next-door neighbors discourage their daughters from playing with the Jefferson children. The acting role Margo receives is too often the maid. She is dogged by restrictive beauty standards governing skin color, hairstyle, the shape of her nose. Her older sister has talent in ballet but her teacher makes clear that she will never succeed as a dancer because of her race. Their options are limited, but they are expected to work harder than others while also being forever docile, kind, and smiling. They are part of a privileged family, but:

Privilege is provisional. Our people have had to work, scrape for privilege, gobble it down when those who would snatch it away were not looking.

Keep a close watch.

All this comes to a head as Jefferson moves through her childhood into the 1960s and '70s when Black Power and feminism make her reevaluate her relationship to the high-class culture of her youth: "The entitlements of Negroland were no longer relevant. We'd let ourselves become tools of oppression in the black community. We'd settled for a desiccated white facsimile and abandoned a vital black culture." She struggles with a feminism that wasn't making much room for non-white women and notes one important privilege that was not extended to them, that of yielding to depression. This is " privilege Good Negro Girls had been denied by our history of duty, obligation, and discipline. We were to be ladies, responsible Negro women, and indomitable Black Women." She, however, does fall into depression, finding that when expectations on one's external life are too stringent, internal rebellion is the only available option.

Her chief consolation is literature and writing. Here is where the book finds its resolution, in retellings of stories, for example reimagining Little Women with Jefferson at the center where she has never before been allowed to live. Stories allow her to explore the limits of identity and to find other possible new selves to inhabit. She writes repeatedly about the danger of falling into anger and negativity when telling the story of one's life, and the turn to writing and the imagination helps her find her way out of this trap.

Negroland is formally innovative with shifts between first and third person as Jefferson looks at her life from the inside and the outside, from interior emotion to exterior judgments. She describes, for example, the beauty standards of her time in the third person, as though to mirror the objectification she experienced as a young girl. She uses lists and categories to reflect the rigid, rule-bound world she lived in. She reflects on memoir itself and asks questions of readers, trying to draw them into her dilemmas. She tells us directly what effects she is trying to create: "Let's look at this from a third-person perspective. It will impose, or at least suggest, more intellectual and emotional control."

There are times, especially in the later sections of the book, when the writing becomes opaque and feels withholding and coy rather than suggestive and rich. But generally Jefferson succeeds at something remarkable: she tells her story while at the same time not only evocatively capturing her era but situating her experiences into a centuries-long cultural tradition. She leads readers to see American history through what will be for many of them a new lens. Through exploring her personal experience of race, class, and gender in America, she complicates our history, doing this with beautiful sentences and a voice that is artfully self-aware.

Spread the word