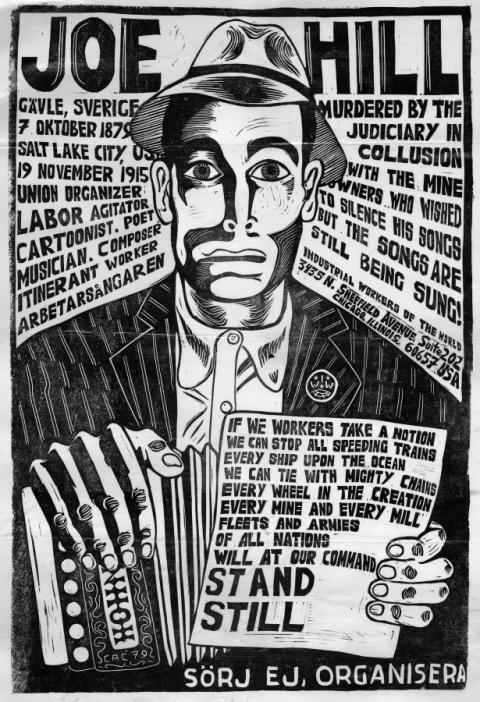

A hundred years ago on November 19, 1915, the song writin’, cartoon scribblin’, parody pushin’ Industrial Workers of the World organizer Joe Hill was unceremoniously executed by firing squad in Utah. Ah, but you might say, the only thing I know about him is that “Joe Hill ain’t never died,” quoting the words of a popular folk song. While it is true that not many folks outside of the embattled labor movement and associated circles know much about Joe Hill these days — that’s a crying shame.

Joe Hill’s struggles for worker’s rights, free speech, the right to a fair trial, and against the inequality of our economic order are still significant today. Born in Sweden on October 7, 1879 as Joel Emmanuel Hägglund, Joe Hill left behind a legacy of activist songs as well as innumerable words to live, and die, by. In fact, when the deputy who was directing the firing squad at Hill’s execution said to his men “Ready, aim,” Hill shouted out “Fire, go on and fire!” — calling the shots until the end. He was not only tasking the state, but also the rest of us, to hurry up and act already.

Hill came to the United States in 1902 and spent the next 13 years organizing workers and agitating for change from New York to California. As the impacts of labor organizing and the Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, strikes were felt, the “copper barons” and corporate cronies were not too happy. Government crackdown on the Wobblies, as members of the IWW are known, was personified in the accusation and then execution of Hill for the murders of a businessman and his son in Salt Lake City. At the time, huge national attention was focused on his case, which was murky at best. Hill’s refusal to testify on his own behalf no doubt contributed to his guilty verdict; reportedly, Hill believed he would be worth more dead than alive to the union cause. Given that 100 years later folks are still talking about him and singing his union songs, odds are good he was right about that.

It’s also true that Hill managed to organize and agitate even beyond the firing squad. Not wanting to be “caught dead in Utah,” he asked to have his body sent to Chicago where it was cremated. His ashes were then distributed, by mail, in 600 envelopes to IWW members, unions and supporters around the world. Reportedly, some ashes were confiscated by the U.S. Postal Service (and just released in the 1990s), some used in building materials (which still can be found in a wall in a Swedish reading room), some were eaten (most recently by Billy Bragg), and some were scattered at events or on the winds of change in Nicaragua, the United States, Canada, Sweden and Australia. So Hill literally lives on not only in song, but also in other remarkable artists and activists. Here are five lessons from Joe Hill that still resonate today.

There is power in a union

Hill believed in the power of a united working class, of organizing to fight the system, not other people. He joined the IWW because it was open to all workers — people of color, women, the un-skilled and foreigners, who were excluded from the AFL at that time. The early 1900s were the heyday of the Wobblies, who were very effective at speaking to people about the necessity of banding together in “One Big Union” to wield power against the corrupt capitalist system to create an industrial democracy.

Unfortunately, the IWW refused to participate in politics at this time — leaving this arena to more conservative socialists who generally scared off the U.S. public. They also refused to sign contracts with bosses, seeing them as too much of a compromise, which meant they were unable to solidify gains won through strikes. Due to these factors, divisions within the IWW, and severe government crackdowns, membership tanked by the mid 1920s — and the union never recovered.

Still, Joe Hill wrote some visionary and cutting words to traditional tunes that live on to tell the glory of the working class. In “Workers of the World, Awaken,” he wrote:

Workers of the world, awaken! Break your chains. Demand your rights.

All the wealth you make is taken by exploiting parasites.

Shall you kneel in deep submission, From your cradles to your graves?

Is the height of your ambition, To be good and willing slaves?

Arise, ye prisoners of starvation! Fight for your own emancipation;

Arise, ye slaves of every nation, In One Union grand.

To build your movement, be inclusive

Recognizing that building people power requires growing a movement’s numbers, Hill wrote songs to inspire solidarity in the ranks and recruit new members. He was an early feminist, at least as much as one can tell from his words about union membership and the important role women could play in class struggle. In “The Rebel Girl,” inspired by the phenomenal radical Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, he penned a targeted lesson to his fellow union brothers. He wrote:

Though her hands may be harden’d from labor, And her dress may not be very fine;

But a heart in her bosom is beating, That is true to her class and her kind.

And the grafters in terror are trembling, When her spite and defiance she’ll hurl.

For the only thoroughbred lady, Is the Rebel Girl.

Creativity gets the goods

As a songwriter, poet, public speaker and organizer, Hill was a cultural worker who knew the power of harnessing creativity and catchy tunes to spread a message where traditional media would fall flat. The Wobblies embraced songs, comics, strikes, soapboxing, and other creative tactics in reaching out to unorganized workers as well as in direct actions on the job site. “A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over,” Hill wrote in a letter to the editor of Solidarity in November 1914. “And I maintain that if a person can put a few common sense facts into a song and dress them up in a cloak of humor, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial on economic science.”

You can’t eat promises

In several songs, it was clear that Hill believed that promises of future gain were no substitute for a better life in the here and now. His parody “The Preacher and the Slave,” of a Salvation Army hymn, “Sweet Bye and Bye,” was the origin of the phrase “pie in the sky,” which stands in for a false promise or unattainable goal.

You will eat, bye and bye,

In that glorious land above the sky;

Work and pray, live on hay,

You’ll get pie in the sky when you die (and that’s a lie).

Don’t mourn, organize

Perhaps Joe’s most famous directive and organizing principle was captured in one of his last communications, a telegram to union compatriot Big Bill Haywood on the eve of his execution. It lives on in the work of nonviolent activists across the globe from Beirut to Paris, and rings especially true as we struggle to move beyond violent acts of terrorism and revenge to dismantle the systems of oppression that drive evil and inequity. “Goodbye Bill,” he wrote. “I die like a true blue rebel. Don’t waste any time in mourning. Organize.”

Thank you Joe Hill, and those that continue to keep his lessons alive by carrying on the work.

Nadine Bloch is an innovative artist, nonviolent practitioner, political organizer, direct-action trainer, and puppetista, who combines the principles and strategies of nonviolent civil disobedience with creative use of the arts in cultural resistance and public protest.

Spread the word