Before I began writing this review I put Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony on my CD player. This symphony, known as the Leningrad Symphony, is the inspiration for a new and wonderful history by M. T. Anderson. As I write these words, the First Movement is approaching its end. The Nazi armies are beginning their ferocious attack on Leningrad and other parts of the Soviet Union in Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa. The symphony’s previous sounds of beauty are replaced by sounds of fear and threat; air raids and bombardments. The fear of Stalin’s police is superseded by the Nazi assault and the fear and death it brings.

Dmitri Shostakovich is one of the greatest composers to have ever lived. His works are musical documents of the times he lived in and timeless works of beauty. From the bloodshed of two world wars, a revolution and counterrevolution, to the fear and brutality of Stalin’s rule, his symphonies, suites and chamber compositions reflect and inform the events which make up that history. The Twentieth Century will be remembered for a multitude of things; among them are the scientific advances we take for granted and the great progress humanity made in improving our species health and prolonging our lives. Despite these positives, though, there is another much darker set of memories. Foremost among the latter are the two world wars. Both wars were ultimately fought for reasons of power and wealth, and both caused the death of tens of millions. There is nothing else in history that compares to these bloody exercises in death. Virtually every nation bears some responsibility for the carrion that rotted into the ground because of these wars and their aftermaths. Naturally, there are two or three nations who bear the bulk of that responsibility, just as there are others who bore the bulk of the casualties.

The Soviet Union was perhaps foremost among the latter. Millions died in its fight against the Nazi armies. More than a million of those died during the Nazi siege of the city of Leningrad–a siege that lasted 872 days. People ate paper and sawdust to survive. Some ate the dead, while a few even killed living humans and ate them. Corpses lay in the frozen streets after they fell dead from starvation and the unbearable cold of the Soviet winter. Thousands of residents were smuggled across a frozen lake out of the city during the winter, yet even then thousands died during their transport. Yet, when spring came, the citizens gathered their minimal strength and buried their dead. Some even planted flowers while many ate grass only because it was the only thing to eat. The story of this siege and the humans who survived it is one of humanity’s greatest and most heroic tales ever.

The siege is the setting of M. T. Anderson’s newest book, titled Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad. Anderson, who writes for the Young Adult market, is perhaps best known for his dystopian novel Feed and the Life of Octavio Nothing Duet, a pair of novels about an African slave in the period of the American colonists’ war for independence with a contrary take on that war and its myths. Symphony for the City of the Dead is a non-fiction work. Part biography and part history, it is a sweeping look at the life of Dmitri Shostakovich, the rule of Stalin, and the fate of Leningrad under the Nazi siege.

Before one begins reading this book, it is essential to dismiss the classification of it as a book for young adults. Like Anderson’s other works, this book transcends marketing classifications. It is a work that, in its majesty, defies expectations and creates new definitions. The composer is the center of the tale, but, like all of us, he is also a plaything (perhaps even a victim) of forces and circumstances much greater than him. Born into pre-revolutionary times and witness/participant in subsequent revolutions, the Shostakovich presented here is first and foremost a musician. Yet, he is also a patriot and a believer in the Soviet revolution. Many of his compositions are an attempt to reconcile these aspects of his intellectual being.

Anderson reflects these facets of Shostakovich are being in this biography. The reader can feel the triumph of the composer when his first symphony is performed in public the first time. They can also anticipate the fear that comes from living under the iron hand of a ruler whose actions are inconsistent and often brutal. The joy his children bring him and the hopes they represent are felt as clearly as the death present every day of the bloody war.

Symphony for the City of the Dead is also the biography of the Leningrad. Always Russia’s city of the arts and music, it is also a city of revolution. Naturally, it buckles at the rule of a man like Stalin, but it keeps its figurative head high. It is this pride that helps its people survives the siege. Daunted and desperate, the spirit of Leningrad’s residents is really the ultimate determinant of its survival. This is why the story of the siege is such a heroic tale. Anderson understands this and makes it the foundation of his history.

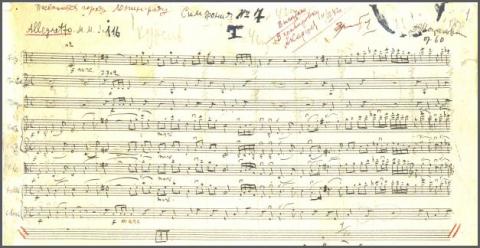

The final piece of this biographical triad is the story of the symphony itself. Titled the “Leningrad Symphony,” it is Shostakovich’s Seventh. Shostakovich attacked the composition with vigor until he and his family were moved out of Leningrad with dozens of other artists. After leaving his city, he sunk into a depression and stopped composing. Anderson writes that Shostakovich told friends he could not write knowing how many people were dying in his city. Of course, he did eventually complete the work and performed it. Its first performance was broadcast over the radio. The reception was instantaneous and thunderous. Shostakovich’s symphony rallied his fellow citizens. Next was a performance in the city of Leningrad itself. It was a city slowly rising from the coma of the siege; musicians were hard to find and, when found, often too weak to play their instruments. Yet, the performance took place, after weeks of rehearsal. Meanwhile, the symphony’s score had been put on microfilm and was being smuggled to the United States, where it would be transcribed onto staff sheets and sent to Arturo Toscanini, who ultimately performed it with the NBC Radio Orchestra to a national radio audience on July 19, 1942. This performance is legendary. Indeed, it is one of the most legendary radio broadcasts of the Twentieth Century. It would help turn the US Congress in favor of joining the Soviet government’s armies to defeat the Nazis.

M. T. Anderson has written a marvel. Symphony for the City of the Dead is a singular and spectacular book. Although I found the politics occasionally too simplistic, this isn’t really a book about politics. It is much more. It is a powerful and wonderfully told narrative about the sheer majesty of the human will and the power of music to not only transcend the depths of human suffering, but to go deep into that pit, struggle there, and deny the victory of those demons who would rule us with hatred, fear and brutality.

Spread the word