A supremely artful feature-length recording of the 1934 Nazi Party Congress, commissioned, according its credits, by order of the Führer, “Triumph of the Will” raises a host of moral and aesthetic questions. (The only real equivalent is D. W. Griffith’s white supremacist magnum opus, “The Birth of a Nation.”) Is “Triumph of the Will” a brilliantly innovative documentary? Is it a propaganda masterpiece? A work of art — or simply, as Zero Mostel says in “The Producers” of his calculated Broadway flop, “a love letter to Hitler”?

Riefenstahl (1902-2003), who produced, directed and for a time distributed the film (reissued on Blu-ray by Synapse Films), denied political intent, claiming that the film was cinema vérité. In reality, it was a colossal photo op. The three-day congress and the movie were planned simultaneously. Riefenstahl had a small army of technicians, including 16 uniformed cameramen, at her disposal. The City of Nuremberg contributed constructions, some designed by Albert Speer, to facilitate her film’s dramatic low or overhead angles, strategic dolly shots and dynamic use of scale.

“Triumph of the Will” is also an organic product of cinema history. Riefenstahl and Speer emulated the monumentalism and ornamental patterns of Fritz Lang’s silent films like “Metropolis”; the Nazi leadership wanted the German equivalent of the Soviet propaganda hit “Battleship Potemkin.” But where “Potemkin” was a film drama designed to look like a newsreel, “Triumph of the Will” was a newsreel contrived to work like a drama, if not a myth.

Riefenstahl’s mass formations of marching members of the Hitler Youth remind many film historians of the dance numbers choreographed in Hollywood by Busby Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Riefenstahl understood the power of synchronized sound. The music in her film is nearly continuous; shots showing a sea of Nazi banners or a forest of upraised arms are edited to the beat.

“Triumph of the Will” is a demonstration of cinematic might — and guile. The impression of a totally organized and controlled Woodstock-like event was achieved through rehearsals, camera placement, inserted footage and post-dubbing, as with the supposedly spontaneous choral singing and the thunderous cries of “Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer!”

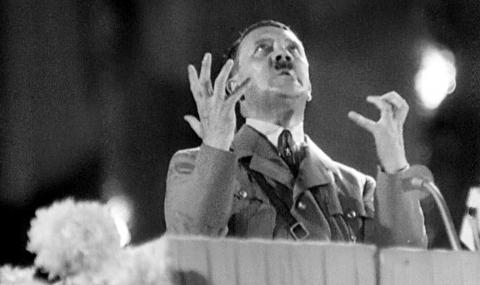

Production numbers aside, “Triumph of the Will” is devoted largely to speechifying. While Hitler is a star performer, who practiced his histrionic gestures before a mirror, his colleagues are not. So stupefying are their exhortations and oaths of fealty, the movie might have been made as much to lull as to agitate. By the time it ends, after a lugubrious third nighttime rally, with a mass rendition of the Nazi anthem “The Horst Wessel Song,” you expect to see a giant swastika go into a hypnotic spin.

A virtual pariah after the war, Riefenstahl was a strenuous advocate for her rehabilitation. Her comeback suffered a major setback with Susan Sontag’s 1975 essay “Fascinating Fascism” — which eviscerated the artist’s whitewashing of her past — but Riefenstahl was embraced by many cinéastes. She was honored by the Telluride Film Festival and profiled in Vanity Fair. The critic John Simon called her “one of the supreme artists of the cinema.” “Triumph of the Will” was named to Anthology Film Archives’ canon of “essential cinema.” The shot in which Hitler and two associates solemnly walk through the assembled mass is quoted in the ceremony that concludes the 1977 “Star Wars.”

Film Culture magazine put Riefenstahl on the cover of its Spring 1973 issue and paid tribute with a dozen articles. One by Ken Kelman, a member of the Anthology Film Archives selection committee, extolled “Triumph of the Will” as “the definitive cinematic obliteration of the division between fantasy and ‘reality.’” For me, it’s impossible not to read that as a warning.

Starting with Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator,” “Triumph of the Will” provided material for anti-Nazi satire; it also figured as an image of the Nazi new order in Hollywood’s wartime efforts. Two examples, “Hitler’s Children” and “Hitler’s Madman” (both quickly made low-budget films from 1943), are available on DVD from Warner Archive.

“Hitler’s Children” is framed by miniature versions of the Nuremberg Congress, with German teenagers clustered around a bonfire consecrating their lives to the Führer. Lurid yet turgid, the movie is a tale of doomed puppy love, Nazi eugenics and sexual sadism. Ads featured the image of a freedom-loving American girl (Bonita Granville, Hollywood’s original Nancy Drew) given a ritual flogging by a member of the SS.

A far better movie, “Hitler’s Madman” evokes a larger Nazi atrocity: the destruction of Lidice, a Czech town where all the male inhabitants were executed in revenge for the assassination of their German overlord Reinhard Heydrich, a key figure in the Nazi hierarchy (who makes a cameo appearance in “Triumph of the Will”).

Like “Hangmen Also Die!” (1943), Fritz Lang’s film on the same subject, “Hitler’s Madman” involved significant German émigré talent: It was produced by Seymour Nebenzal, whose credits included Lang’s “M,” and was directed by the recently arrived Douglas Sirk. Eugen Schüfftan, who shot “Metropolis,” worked (uncredited) on the cinematography; Edgar G. Ulmer (also uncredited) was responsible for the sets.

The Nazis are portrayed as viciously anti-Christian. (Although the screenplay was partly written by the Yiddish-language playwright Peretz Hirschbein, Nazi anti-Semitism is not a factor.) Religious iconography adds to the dark fairy-tale ambience. The most alarming special effect is John Carradine’s performance as Heydrich, gaunt and implacable as a medieval Death.

Sirk intended his movie to be “almost like a documentary,” Carradine’s cold, self-dramatizing impersonation not least. The filmmaker had once met Heydrich at a Berlin reception. “Carradine was Heydrich,” he told an interviewer, adding, “a lot of Nazis behaved like Shakespearean actors.”

OTHER NEWLY RELEASED DVDS

EXPERIMENTER Michael Almereyda’s experimental docudrama stars Peter Sarsgaard as the social scientist Stanley Milgram, whose psychological tests, inspired in part by the trial of the Nazi official Adolf Eichmann, were designed to plumb the nature of totalitarian obedience. In her review for The New York Times, Manohla Dargis called it “less a straight biography than a diverting gloss on human behavior, historical memory and cinema itself.” Available on Blu-ray, DVD and Amazon Video. (Magnolia)

NIGHT WILL FALL Made for HBO and now on DVD, André Singer’s restrained but harrowing documentary depicts the fate of the atrocity footage shot by British cameramen attached to the soldiers who liberated German concentration camps. “Not a film you’re likely to forget,” Mike Hale wrote in The Times. (Warner Bros.)

PRESSURE POINT Sidney Poitier plays a tightly wound prison psychiatrist saddled with Bobby Darin’s American Nazi patient in this 1962 drama produced by Stanley Kramer, reissued on Blu-ray. The Times critic Bosley Crowther praised Mr. Poitier’s “coolly forceful performance” and noted that, “as was intended, Mr. Darin’s portrayal should make anyone recoil.” (Olive Films)

SHADOWS AND FOG Woody Allen visits the dark heart of Europe in this stab at a comic, mock Expressionist tribute to Franz Kafka, Fritz Lang and Kurt Weill, now available on Blu-ray. The Times critic Vincent Canby called the movie “a mixture of the sincere, the sardonic and the classically sappy” when it opened in New York in 1992. (Twilight Time)

WELCOME TO LEITH The documentarians Michael Beach Nichols and Christopher K. Walker report on a neo-Nazi white supremacist attempt to take over a small town in North Dakota. In his review for The Times, Stephen Holden described a few moments in which “the film might be mistaken for a horror movie about an alien invasion.” On DVD. (First Run Features)

[J. Hoberman’s is a celebrated film critic. His books include Film After Film (Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema?) and An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War.]

Spread the word