Rick, a 45-year-old white computer engineer in Maineville, Ohio, realized he was really good at fixing things as a young child. But he never liked getting dirty, so his dream job was to fix things without getting dirty. Computers were just the ticket. After five years in the Navy, Rick finally finished getting his two-year associate’s degree, and, determined to set a good example for his children, completed his bachelor’s degree right before turning 40. As a computer engineer, he has earned between $85,000 and $101,000 a year and considers himself middle class.

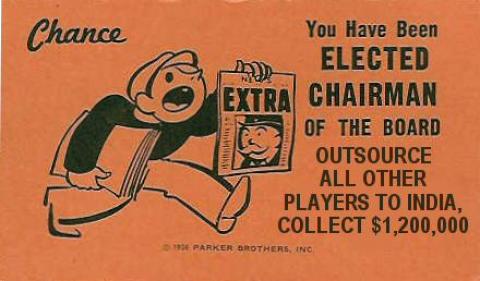

He’s also been laid off twice, at two different companies—and both times, his job was offshored to India. The last time, he actually had to train his replacement in order to receive his severance. His entire department was being transferred to India, and the company flew the new workers to the United States to be trained by the very people whose jobs they were taking.

The transfer to cheaper sources of once-safe occupations is just one of the ways work has become less secure for many people in the middle class. The debate this election cycle about how to shore up the American middle class and the longer-term worry that automation will chip away at the labor market both miss a more proximate and pressing reality: knowledge work, including tech jobs, are already being shipped overseas. What happened to manufacturing jobs a generation ago is now being repeated in the knowledge economy, linking the fates of the professional class and the working class together.

NO EXCEPTIONS FOR KNOWLEDGE WORKERS

Rick’s layoff came after the company was bought out by a big, publicly traded corporation. The original company was privately held; Rick described it as a "tight-knit group, and more of a family culture." But now the culture was much more siloed and corporate. And, more important, the company was now "beholden to shareholders." In addition to Rick’s department being offshored, a total of 120 staff members were laid off and their jobs outsourced.

Rick’s story is becoming much more common now among professions once considered safe from the lure of cheaper labor. Companies are now sending many so-called "skilled" positions offshore, including once high-paying jobs in the financial and tech sectors. The transfer to cheaper sources of once-safe occupations is just one of the ways work has become less secure for many people in the middle class.

Recent college graduates are increasingly taking jobs that don’t require a degree, at least until a career path opens up somewhere else. Journalists of all kinds are likely to be freelancers, forced to be constantly pitching new work to new outlets to earn a living. University faculty members are increasingly hired as adjuncts, paid by the course in what amounts to roughly the minimum wage.

The spoils, of course, are reserved for corporate executives and managers, who now face intense pressures from the financial class to lower costs and boost profits. All of these trends lead, in some fashion or another, back to the outsized and extractive role played by the people and institutions at the very top of the food chain—private equity firms and hedge funds. As a result, the trappings of a secure middle-class existence—housing, child care, college, retirement, and even a decent vacation—fall further out of reach.

IT STARTS AT THE BOTTOM

Yet while those changes take place, much of the popular conversation, especially during the current election season, still focuses on what’s happening to middle-class professionals, and especially younger ones.

Those issues are real and growing, but when you compare them—doubling or tripling up in an apartment in a hip neighborhood to afford rent, say—to those of a thirtysomething parent working as a cashier with unstable hours, struggling to find and pay for child care, it’s the mom in a crumbling neighborhood who needs much more of our political attention and public concern. Not only are her set of challenges faced by many more Americans than those of the upwardly mobile urban professionals, but the pressures that both groups face are becoming more intimately linked than ever before.

The philosophy that allows employers to schedule their hourly workers week to week, with little advance notice, is the same one that expects salaried workers to be "on" 24/7. Unless we can coalesce around the need for a much higher quality of life for the new working class, then anyone who isn’t truly affluent will continue to live on a precipice of economic anxiety and insecurity.

Why? Because the philosophy that allows employers to schedule their hourly workers week to week, with little advance notice, is the same one that expects salaried workers to be "on" 24/7, responding to emails and taking conference calls that disrupt family and leisure time. The policies that stripped away our factories are the same policies that are now yanking professional jobs out of the country, following the path that manufacturing jobs took decades ago.

The forces that hit the working class first and hardest are now inflicting plenty of damage on the middle class, too. If we really want to save it, we’ve got to work together—from the bottom up.

This article is adapted from Sleeping Giant: How the New Working Class Will Transform America by Tamara Draut. Copyright © 2016 by Tamara Draut. It is published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC.

Spread the word