The Fight for 15 movement claimed its biggest victories to date last week, with both New York and California passing major minimum-wage increases.

California’s rate, currently one of the highest in the country at $10 dollars per hour, will rise incrementally and reach $15 dollars by 2022. In New York, the wage floor will go up according to business size and location: larger New York City employers (ten or more employees) must pay at least $15 by the end of 2018, while smaller employers in the city (fewer than ten employees) will have until the end of 2019 to meet that mark.

Westchester County and suburban Long Island wages will hit $15 by 2022. And upstate New York employers will have to pay employees at least $12.50 by the end of 2020, after which the state will determine how to get to $15.

It’s disappointing that the $15 requirement won’t cover all of New York state for some time, and that upstate New York workers won’t see a $15 minimum for several years at least. Unlike California, New York also still allows tipped workers to be paid a lower wage. But considering the trajectory of the US minimum wage over the past four decades, these are enormous wins. Simply put, the US has never seen an increase this large.

Maximizing the Minimum

The federal government’s minimum-wage system is fairly primitive. It has no formula for setting pay minimums, and no mechanism for keeping the minimum wage in line with cost-of-living changes.

In the post–World War II years, the mandated wage at least increased fairly regularly. But beginning in the 1980s, and continuing into the ’90s and 2000s, policy makers let it stagnate. The current federal minimum of $7.25 is a poverty wage that, when adjusted for inflation, sits far below its historic peak. If the minimum wage had kept pace with worker productivity since the 1960s, it would be about $21 per hour.

Over the past two decades, activists have worked to pass living-wage ordinances at the local level, hoping to put pressure on states and the federal government. Some states acquiesced, boosting wages and instituting annual adjustments for inflation. In the early 2000s, even a few cities passed minimum-wage increases.

The push for higher wages temporarily waned after the 2008 financial crisis.

But after Occupy in 2011, and the wave of fast-food strikes the following year in New York City, the movement to raise wages took a new turn and a bolder stance: $15 an hour and a union. When the campaign first began, that pay demand seemed like a pipe dream: $15 was more than double New York’s minimum wage at the time ($7.25), and fast-food workers — often considered unskilled and dispensable — seemed like unlikely candidates to challenge multi-billion-dollar corporations.

Yet the call for $15 resonated. Soon after the emergence of Fight for 15, labor and community activists won a ballot initiative to establish a $15 minimum wage in the small airport town of SeaTac, Washington. The Seattle City Council followed suit, establishing the same wage floor.

Within a few years, over thirty cities and counties around the country had approved higher minimums, ranging from $8.50 to $15 an hour. (At least a dozen large employers — ranging from McDonald’s and IKEA to the University of California — also agreed to raise their lowest wages.)

And now, two of the biggest states in the country have added to that string of victories.

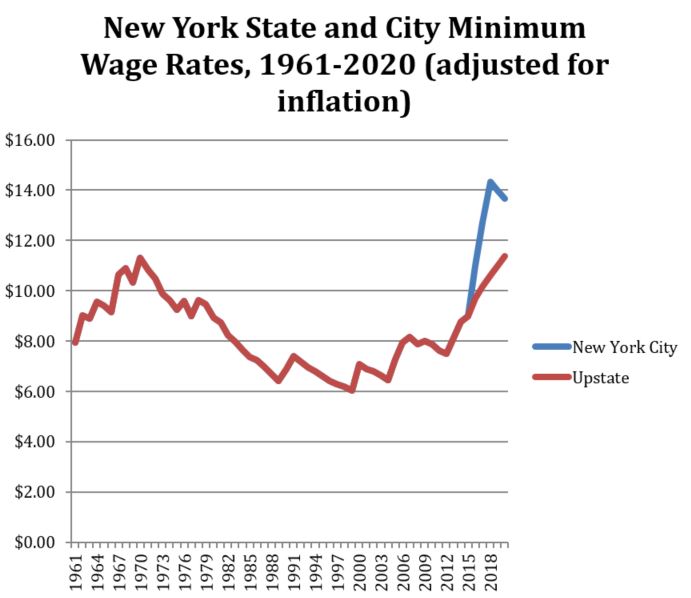

Note: Wage rates are adjusted for inflation according to the CPI-U, and CPI-U projections. This chart assumes the New York City rate will remain at $15 once it reaches that level.

While the New York deal won’t bring $15 right away, the chart above illustrates the magnitude of the win. After adjusting for inflation, even the upstate rate of $12.50 exceeds the peak (real) rate in 1970.

To be sure, a $15 minimum wage is not a solution to poverty, bad jobs, or eroding worker power. Many workers will still face workplace discrimination, health and safety violations, wage theft, irregular schedules, and underemployment. Moreover, employers may balk at the new wage rules and try to fight implementation. And without a union to back them up, workers may be afraid to speak up for their rights.

But the increases are still a major win. The New York and California plans will bump up wages for more than nine million workers. Persistent labor market discrimination means that people of color continue to receive lower pay, on average, than white workers. If the federal minimum wage were pushed up to $15, it would provide direct and indirect wage increases for approximately 54 percent of all black workers and 59 percent of Latino workers.

The battles for $15 have been won through hard work: organizing workers, building for strikes, creating coalitions, and challenging the standard neoclassical orthodoxy that argues wages should be set by employers and employers alone. Living-wage campaigns assert that workers are worth more than a paltry minimum wage, that we should pay people based on need rather than the supposedly iron laws of supply and demand.

Much of the public recognizes this. For decades, large majorities (even among Republican voters) have supported hiking the minimum wage. Yet Democratic politicians, reluctant allies at best, have moved at a glacial pace.

This landscape of lip-service support may be changing, however. Suddenly we see some politicians — including New York governor Andrew Cuomo, who for five years offered erratic and unpredictable support before pushing for a more generous wage — embracing the cause.

While this is a welcome development, we shouldn’t forget what produced the newfound enthusiasm: voter support and, even more importantly, the growing number of worker strikes.

Failed Theories, Bigger Fights

Can the country really afford a $15 minimum wage?

Opponents claim that raising the minimum wage will drive employers to cut jobs — it’s economics 101, they say. But the real world doesn’t usually work according to abstract economic models, and current research, for the most part, doesn’t support the higher-wages-equal-fewer-jobs argument.

Employers have many “adjustment channels.” They can, and do, deal with higher wages by decreasing turnover, increasing productivity, redistributing wages within the firm, and modestly raising prices.

Boosting wages also tends to create new jobs. For example, a University of California Berkeley study found that while up to 78,000 workers might lose employment as a result of New York’s minimum-wage bump, the remaining workers will have more purchasing power to spend in the local economy. This expanded consumption would generate over 81,000 new jobs, cancelling out any net job loss.

And even if employers end up shedding more positions than they create, it might not be such a bad thing. The US has hundreds of thousands of crappy, dangerous jobs — low wages, no benefits, few hours. If higher pay prevents employers from relying on substandard work that can be automated, labor can end up better off.

Of course, the movement would then need to leverage the momentum of recent successes to push for policies that benefit workers who lose jobs (or never get one in the first place).

For example, if we made higher education free, more young workers could leave the paid labor force altogether and become full-time students. A decent social-security system and restored pensions would enable seniors to actually retire instead of taking up extra hours at Walmart. Decent unemployment benefits and quality education and training would help workers make a career change if they got laid off.

A basic income grant, a federal jobs program, public subsidies to make child care and transportation affordable or free — there’s no shortage of great policy ideas that could dramatically improve the lives of the unemployed and underemployed.

Of course, good ideas aren’t enacted simply because they make sense. The minimum-wage movement must build on its victories to organize workers into unions, strengthen and revitalize existing labor organizations, and link up with other progressive forces such as Black Lives Matter, immigrant rights groups, and Bernie Sanders supporters.

Ironically, it was the Onion that best summarized the challenges facing Fight for 15. After presenting a list of pros and cons for hiking the minimum wage, it declared $15 a “bargain compared to cost of creating actual social safety net.”

Indeed, despite its victories, Fight for 15 is no substitute for a radical, anticapitalist agenda. The campaign will be truly groundbreaking if it can become part of something bigger — part of a project to build working-class movements that challenge the very concept of wage labor.

Stephanie Luce is a professor of labor studies at the City University of New York's Murphy Institute and the author of Labor Movements: Global Perspectives.

If you like this article, please subscribe or donate to Jacobin magazine.

Spread the word